In July of 2015, the math teacher and author of the Truth in American Education blog Barry Garelick wrote an article in which he described the convoluted explanations to simple math problems that students were expected to produce under Common Core, the logic being that the ability to describe one’s mathematical thinking in detail was a sign of “deep understanding.”

As Barry pointed out, however, the process of describing one’s thinking became an end in itself rather a sign of actual comprehension. Essentially, students were being trained to display a set of behaviors that made it appear as if they were thinking deeply, whether or not they truly understood—a phenomenon he termed “rote understanding.”

I still think this is one of the most brilliant phrases I’ve come across in the edu-blogosphere; it perfectly captures the superficial, performative quality that is often held up as a signal of “true education” or “authentic learning.”

So with Barry as my inspiration, allow me to propose a term of my own: ladies and gentlemen, I give you “rote creativity.”

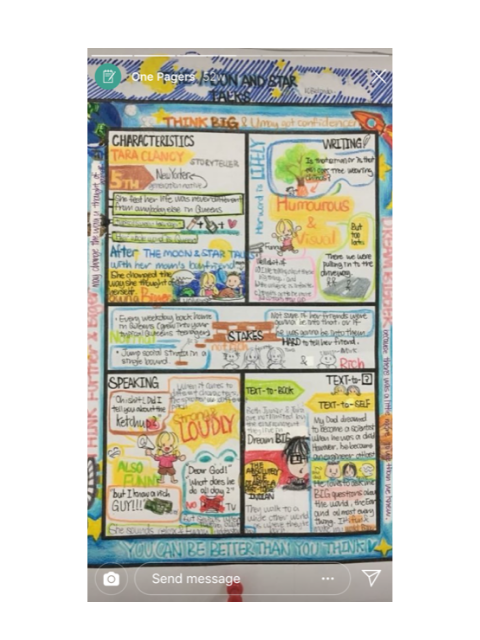

This is a term that first popped into my head one night when I was browsing high-school English related hashtags on Instagram and came across the following:

I did some poking around Teachers Pay Teachers and discovered that apparently these one-pagers have become, like, a thing. (A colleague who teaches high school confirmed that the English teachers at her school love to hang them in the corridors.)

In case you missed the caption below the third image, the point of these sheets is to “spark creativity” and help students “process, analyze, and synthesize” information.

And from another sample pitch:

Are you drowning in essays? Looking for a way to have students show analytical thinking about a text in a meaningful way that won’t send you to the crazy house? Try the one pager as an alternative response to literature. Not only does it encourage students to think creatively and abstractly, but also it teaches them how to use quotations, symbolism, and images to convey how they experience a text.

Clearly this is a much richer and more authentic form of assessment than, oh, I don’t know, writing a research paper. Because look! Bright colors and neat pictures! Copying quotations in pink marker really helps students deep-dive into the text and develop those higher-order thinking skills!

Yeah, right. Sure.

And people wonder why students have trouble writing when they get to college.

If this doesn’t illustrate (no pun intended) the gap between educational rhetoric and reality, then I give up.

I understand that teachers are stressed out and overburdened; that their classes are too large; that they don’t have hours and hours to devote to grading five-page essays. And I understand that an education system that has come to revolve around preparing students to answer multiple-choice questions and crank out five-paragraph essays for stultifying, poorly written state tests does not exactly encourage risk-taking. I certainly read enough timid, disengaged essays to understand why teachers would want to jazz things up.

But this is… not the solution.

The irony is that this is the sort of assignment embraced by people who claim to be anti-worksheet, but in reality is clearly nothing but a gussied-up worksheet. It serves no other other purpose than to (poorly) create the illusion that students are crossing boundaries and doing fabulous, inspired work when nothing of the sort is occurring. It’s not as if students even get to decide what sort of information should go in the little boxes; they just get to decorate them. To invoke the cliché, this is the literal definition of “in the box” thinking.

This really is an insult to the very concept of creativity. It’s shallow and gaudy and childish; it makes no real intellectual demands; and it sidesteps one of the central purposes of English class, namely learning to express complex ideas cogently in extended pieces of writing.

True creativity is not something that is dictated by a formulaic, third-grade-level assignment (and certainly not a single-page one). In the real world, it is normally driven by sincere curiosity and/or a desire to solve an actual problem. Much of the time it happens by accident or is driven by necessity. It can involve periods of tinkering that are frustrating and unproductive, and it often results from a lot of time and effort and knowledge. It’s just as likely to be quiet and unobtrusive as it is loud and showy.

To be sure, teaching writing well is an incredibly hard, often ungratifying, task; there are so many moving parts, so many pieces to integrate, especially if students haven’t read enough to have developed a sense of how words can be put together on the page. There’s nothing rote about it, and there’s no quick fix.

Assignments like this are fundamentally unfair to students, who end up woefully underprepared for what college-level writing entails; and they are also unfair to the teachers and professors who do make real demands on students and find themselves the targets of their resentment.

Erica,

On the topic of creativity:

I was once in a meeting with a colleague and I referred to efforts with helping my students develop their creative thinking.

After some confusion, I realized that I needed to explain that creative thinking is what we employ any time we develop (or “create”) an answer, idea, or approach (usually in response to a question identified through analytical thinking).

Unfortunately many people don’t seem to understand the difference between the development of these critical thought processes and simply coloring/drawing.