by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 10, 2015 | ACT Essay, Blog

For this final part of the “writing the new ACT essay series,” we’re going to look at what is probably the most challenging aspect of writing the essay: the counterargument.

For those of you unfamiliar with the term, a counterargument is simply a perspective that refutes your main argument. Simply put, if you’re arguing that technology does more good than harm, the counterargument is that technology does more harm than good.

Before we look at an example, there are a couple of things I’d like to point out: first, I cannot stress how important transitions are in writing effective counterarguments. Without them, your reader will have no way of following your train of thought and will find it very difficult – if not impossible – to distinguish between which ideas you agree with and which ideas you disagree with.

Another key element of good counterarguments is the concession – that is, the acknowledgement that some aspects of the opposing argument are valid. This is the most unfamiliar aspect of counterarguments for many students – isn’t the whole point of a counterargument to “disprove” the opposing argument?

Ultimately, yes, the goal is to show why your argument wins out. That said, the point of a concession is to demonstrate that you’ve thought about an issue carefully, in a nuanced way rather than in straightforward black/white, good/bad terms. When presented clearly, this type of consideration actually strengthens your argument.

You can use this general template to create a counterargument:

According to Perspective x, _______________________. On one hand,

-it is true that _______________________.

-this claim has some merit because _______________________.

-the claim that _______________________ does have some validity.

On the other hand,

-this perspective fails to consider that _______________________.

-this claim overlooks the fact that _______________________.

Let’s see how this would play out in a sample paragraph that uses a personal example (yes, those are still fine). It doesn’t use the template exactly, but it’s pretty close.

Again, we’re going to use the sample prompt released by the ACT. For the purpose of this exercise, we’re only going to look at one of the perspectives; trying to work with more than that would be too confusing. In fact, you should generally avoid integrating more than one outside perspective per paragraph, unless you are a stellar writer who is already comfortable with this type of back-and-forth.

(Abridged) prompt: Automation is generally regarded as a sign of progress, but what is lost when we replace humans with machines? Given the accelerating variety and presence of intelligent machines, it is worth examining the implications and meanings of their presence in our lives.

Perspective 1: What we lose with the replacement of people with machines is some part of our humanity. Even our mundane encounters no longer require from us respect, courtesy, and tolerance for other people.

Thesis: Technology should be seen as a force for good because it creates new possibilities for people as well as a more prosperous society.

1) Topic sentence: introduce your argument (1 sentence)

Over the past few decades, new forms of technology have created ways for people communicate with one another more quickly and easily than ever before.

2) Elaborate on your argument, and provide a specific example (2-3 sentences)

From Skype to iphones apps to Facebook, technology erases borders, allowing us to talk to people halfway around the world as if they were in the next room. I have personally benefitted enormously from these technologies: my family immigrated to the United States from China when I was 6 years old, and over the past decade, gathering around the computer to chat with my grandparents and my aunt in Beijing has become a weekly ritual. Although I am sorry that we no longer live next door to them, as we did when I was little, I am nevertheless grateful to be able to see their faces and keep them updated on the details of my daily life – something that would be impossible without “smart” machines.

3) Introduce outside perspective: 1-2 sentences

Not everyone is so enthusiastic about the effects of new technologies, however. Perspective 1 offers a typical complaint, namely that the replacement of people with machines “causes us to lose some part of our humanity.”

4) Acknowledge that the perspective isn’t entirely wrong, and explain why (2-3 sentences)

On one hand, this complaint does have some merit. Walking down the street or sitting on the subway, I am often struck by the sheer number of people staring glassy-eyed into their phones. Sometimes they are so busy texting that they nearly bump into others, demonstrating a clear lack of courtesy and tolerance (notice how this statement weaves the viewpoint naturally into the writer’s argument).

5) Transition back to your argument and reaffirm it (3-4 sentences)

On the other hand, though, the benefits of technology far outweigh an occasional unpleasant sidewalk encounter – at least from my perspeective. Rather than isolate me from the world (notice how this statement indirectly refutes the counterargument), “smart” technology has served primarily to facilitate my relationships with others, not to replace them.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 10, 2015 | ACT Essay, Blog

After providing an overview of the new ACT essay and some possible approaches to it in my previous post, I want to now discuss one particular – and very important – skill involved in writing it: incorporating other perspectives into your own argument for support.

If you’ve ever written a research paper, you probably have some experience integrating the ideas of people you agree with into your writing. (And if you haven’t, you’ll get an introduction to doing so in this post.) That said, I find that most high schools do not explicitly teach students to weave supporting quotations, ideas, etc. fluidly into their writing. The quotes are there, but they’re often integrated awkwardly into the larger argument.

Very often, students assume that they do not really need to spend time introducing or explaining their quotes because they seem so self-explanatory. They’re there to support the argument, and if the argument is clear, then the point of the quotation is obvious…right? Well, not always.

The problem is that analytical writing requires much more explanation than might seem necessary. Generally speaking, people write about topics with which they are familiar. Because they know a lot of about their topics, they are often unaware of the gaps in other people’s understanding. As a result, it simply does not occur to them how explicit they need to be, and they end up inadvertently leaving out information that is necessary to understanding their thought process.

When you explain an idea – any idea – in writing, you must take your reader by the hand, so to speak, and lead them through each step of your thinking process so that they do not get lost. Introducing other people’s words or ideas in such a way that makes clear the relationship between your argument and theirs is a key part of that process. Otherwise, it’s as if you’ve skipped ahead a few steps, leaving the reader to stop and try put together the pieces. If there’s one thing you don’t want to do to your reader, it’s make your ideas hard to follow. That goes for school, the ACT, and any other writing you might do for the next sixty or seventy years.

Once again, we’re going to work with the sample prompt released by the ACT. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 8, 2015 | ACT Essay, Blog

For those of you unacquainted with it, the pre-September 2015 version of the ACT essay asked students to weigh in on a straightforward, usually high-school/teenager related question, e.g. “Should students have to maintain a C average in order to get their driver’s license,” or “Should schools establish a dress code?” Although the ACT was always pretty clear about the fact that a counterargument was necessary for a top score, it was traditionally possible to write the essay without taking one into account.

Now that’s no longer the case.

If you take the ACT with writing now, you will be given a prompt presenting a topic, then asked to consider three different viewpoints. You can write a straightforward agree/disagree thesis in response to one of the viewpoint (the simplest way to go) or fashion an original thesis based on one or more of the viewpoints (more potential for complication).

Regardless of which one you choose, you must take each of the views into account at some point in your essay.

(Click here for a sample prompt, or see below, and here for sample essays).

In comparison to the old ACT essay, the new one certainly looks more complicated: rather than one single question, there are now three separate perspectives to contend with. There’s a lot of information to absorb, analyze, and write about in a very short period.

In fact, the new ACT essay is essentially a synthesis essay, much like the one on the AP English Comp exam; the various viewpoints are simply presented in condensed form because of the 40-minute time limit.

If you’re a senior retaking the ACT and took the AP Comp test (or the AP French/Spanish/Italian language test) last year, you have a leg up because you have some experience integrating multiple arguments into your writing. If you’re a junior writing this type of essay for the first time, however, it can seem a little overwhelming.

Having tutored three out of those four exams, I’ve learned to explain some things upfront.

The most important one is that the primary focus of a synthesis essay should still be your argument. The requirement that you consider multiple perspectives does not alter that fact. Rather, your job is to talk about those various perspectives in relation to your own point of view. You can, therefore, think of the ACT essay as a standard, thesis-driven essay, just one in which you happen to discuss ideas other than your own. Your thoughts stay front and center.

Instead of viewing the various perspectives as something to make your task more complicated, think of it the opposite way: those perspectives are giving you material to work with so that you don’t have to come up with all the ideas on your own. They’re actually making your job easier.

To simplify things, you should initially take the various perspectives into account only as aids for determining your own point of view. Once you’ve come up with a clear thesis, you can then go back and work the different perspectives into your outline. To keep things simple again, focus on discussing one perspective (agree/disagree) in each paragraph; if you start to bring in too many ideas at once, you’ll most likely get lost.

I also cannot stress how important it is to spend a few minutes outlining. Don’t worry about getting behind — this is time well spent. For most people, the biggest difficulty in writing this type of essay is keeping the thread of their own argument and not getting so sidetracked by discussions of other people’s ideas that it becomes difficult to tell what they actually think. When you’re learning to write about other people’s ideas, this is the rhetorical equivalent of a tightrope walk. If you know where your argument is going from the beginning (and even have topic sentences that continually pull it back into focus, should it start to drift off in the course of a paragraph), you’re far more likely to stay on track.

If, on the other hand, you just start to write, there’s a pretty good chance your writing will either become repetitive or start to wander eventually, making it difficult for your readers to figure out just what you’re actually arguing.

Let’s look at an example of an outline based on the sample prompt released by the ACT.

(Abridged) prompt: Automation is generally regarded as a sign of progress, but what is lost when we replace humans with machines? Given the accelerating variety and presence of intelligent machines, it is worth examining the implications and meanings of their presence in our lives.

Perspective 1: What we lose with the replacement of people with machines is some part of our humanity. Even our mundane encounters no longer require from us respect, courtesy, and tolerance for other people.

Perspective 2: Machines are good at low skill, repetitive, jobs, and at high speed, extremely precise jobs. In both cases, they are better than humans. This efficiency leads to a more prosperous and progressive world for everyone.

Perspective 3: Intelligent machines challenge our longstanding idea of what humans are and can be. This is good because it pushes humans and machines toward new possibilities.

Thesis: While machines have enormous power to make our lives easier and more efficient, we must be careful not to become so dependent on them that we compromise our humanity.

Outline

I. Intro: increasing reliance on machines, 20-21st c.

II. Support: machines make life easier

-Ppl injured, increase mobility, lead normal lives

-Perspective 3

III. Against : too dependent = bad b/c texting, ignore ppl/physically present

– personal ex.

-Perspective 1

IV. Against: too dependent = bad b/c human oversight important f/work

-Work example: manufacturing high-tech parts

-Perspective 2

V. Conclusion: dangers of over reliance on machines, where are we going?

Notice a few things about this outline:

1) The organization of the essay matches the organization of the thesis (advantages, then disadvantages). This is not the only possible organization — you could just as easily discuss the disadvantages in the first two body paragraphs, then the advantages in the third — but it does save you some time in terms of trying to decide to arrange things.

2) Each paragraph focuses on one idea and integrates one outside perspective, preventing you from trying to tackle too many ideas at once and making it difficult for the reader to follow your argument.

3) Words are abbreviated in order to save time. The goal is to be just specific enough to keep yourself focused.

Next, see Part 2 of this series, which covers how to discuss supporting ideas and weave quotations smoothly into your arguments.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 7, 2015 | Blog

From Bloomberg:

Students in the high school class of 2015 turned in the lowest critical reading score on the SAT college entrance exam in more than 40 years, with all three sections declining from the previous year. Meanwhile, ACT Inc. reported that nearly 60 percent of all 2015 high school graduates took the ACT, up from 49 percent in 2011. (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-09-03/students-bombed-the-sat-this-year-in-four-charts)

Oh well, good thing the new SAT is right around the corner. Without all those obscure words and irrelevant passages, scores should start to artificially increase stabilize.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 6, 2015 | Blog, College Admissions

I don’t wade into the waters of college essays very often, but for those of you who are thinking about starting them or are already in the process of writing them, I’m going to offer some tips regarding things to avoid.

While the most effective college essays do tend to share some general features (specific, stylistically varied, have a clear story arc, are unique to the writer), they come in so many different varieties that there is no real formula to writing one. For that reason, I find it difficult to prescribe a particular set of “do’s.”

Ineffective essays, on the other hand, tend to exhibit a much clearer set of characteristics.

So having said that, I’m going start with one very big cliché to avoid: (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 1, 2015 | Blog, Grammar (SAT & ACT)

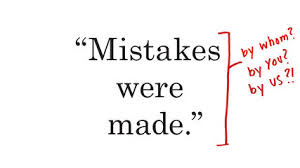

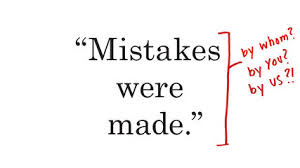

Although I can be a stickler for grammar (a tendency that I do my best to keep in check in non-teaching/blogging/grammar book-writing) life), there are nevertheless a handful of “rules” that I really and truly could not care less about. Among them are split infinitives (a ridiculous attempt to treat English like a purely Latin-based language that fails to take its Germanic roots into account); the use of “they” to refer to a singular noun when gender is not specified (no, “he” is not actually neutral, and seeing it used that way increasingly feels like an anachronism); and the prohibition against the passive voice.

The passive voice, in case you’re unfamiliar with the term, involves flipping the subject and object of a sentence around to emphasize that an action was performed by someone/something, e.g “The man drank the water,” becomes “The water was drunk by the man.” It is also possible to omit the “by” part and simply say “The water was drunk,” the implication clearly being that it was drunk by someone.

On the SAT and the ACT, answers that contain passive constructions are almost always wrong, if for no reason other than that they tend to be unnecessarily wordy and awkward. And in fact, passive constructions are by definition wordier than active ones. The awkward part… Well, that’s up for debate.

The use of the passive voice is an issue that blurs the line between grammar and style; there are instances in which the passive creates wordy, awkward horrors, but there are also cases in which it is useful to create a particular emphasis. For example, most people would never even be tempted to say “The car keys were lost by my mother.” On the other hand, it sounds perfectly normal to say “The bill was passed by Congress yesterday” — the emphasis is on the fact that the bill went through.

I always assumed that the “no passive” rule was simply something that had been cooked up a couple of centuries ago by linguistic purists (much like the “no split infinitives rule”) and handed down from masters to disciples through the ages. In this case, however, “through the ages” means more like “since the 1950s,” more specifically since the popularization of The Elements of Style.

Now, I confess to having a soft spot for Strunk and White’s chef d’oeuvre. It was the first grammar book I used in high school English class (we were handed copies in September and instructed to memorize it — progressive education this was not), and it introduced me to all sorts of wonders like non-essential clauses and the requisite semicolon before “however” at the start of a clause.

As I recently discovered, though, Strunk and White got some things wrong. As is, major, big-time, crash and burn wrong. (In my own defense, I haven’t looked at the book in years). I knew that some people had “issues” with the “little book” — to put it diplomatically — but I always wrote that off as a matter of personal taste. Then, a couple of days ago, I stumbled across Geoffrey Pullum’s delightfully titled Chronicle Review article “Fifty Years of Stupid Grammar Advice,” in which the author takes it upon himself to enumerate the ways in which Strunk and White managed to mangle their explanation of the passive voice. Indeed, they barely understood it themselves.

As Pullum points out:

What concerns me is that the bias against the passive is being retailed by a pair of authors so grammatically clueless that they don’t know what is a passive construction and what isn’t. Of the four pairs of examples offered to show readers what to avoid and how to correct it, a staggering three out of the four are mistaken diagnoses. “At dawn the crowing of a rooster could be heard” is correctly identified as a passive clause, but the other three are all errors:

- “There were a great number of dead leaves lying on the ground” has no sign of the passive in it anywhere.

- “It was not long before she was very sorry that she had said what she had” also contains nothing that is even reminiscent of the passive construction.

- “The reason that he left college was that his health became impaired” is presumably fingered as passive because of “impaired,” but that’s a mistake. It’s an adjective here. “Become” doesn’t allow a following passive clause. (Notice, for example, that “A new edition became issued by the publishers” is not grammatical.)

I’ve heard horror stories about college students getting marked down on papers because their TAs/professors mistakenly thought they had used the passive voice when that was not the case at all. (And at any rate, no one should get marked down just for using the passive voice.) It’s always a problem when people have knee-jerk reactions to concepts they don’t fully understand.

To be clear, though, I understand the pushback against the passive, especially on standardized tests. Standardized tests are, by nature, crude tools; their goal is to touch on the most common and misuses of various structures. I’ve read enough wordy, repetitive, marginally coherent SAT/ACT essays to last a lifetime, and given that experience, I don’t have a problem with the tests’ perhaps overzealous approach. In this case, however, know that the rule is a little more flexible in real life. But try not to go crazy, or a hard time will undoubtedly be had by your readers.