by Erica L. Meltzer | Jun 7, 2016 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

Manuel Alfaro, a former executive director at the College Board, has written a series of posts on LinkedIn detailing the myriad problems plaguing the development of the new exam.

According to Alfaro, not only were many of the items developed for the first administration of the test extraordinarily problematic (see below), but many of the items that appeared on the test were not actually reviewed by the Content Advisory Committee until after the test forms had been constructed.

Committee members repeatedly attempted to call David Coleman’s attention to the problem, but were ignored. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jun 1, 2016 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

In the spring of 2015, when the College Board was field testing questions for rSAT, a student made an offhand remark to me that didn’t seem like much at the time but that stuck in my mind. She was a new student who had already taken the SAT twice, and somehow the topic of the Experimental section came up. She’d gotten a Reading section, rSAT-style.

“Omigod,” she said. “It was, like, the hardest thing ever. They had all these questions that asked you for evidence. It was just like the state test. It was horrible.”

My student lived in New Jersey, so the state test she was referring to was the PARCC.

Even then, I had a pretty good inkling of where the College Board was going with the new test, but the significance of her comment didn’t really hit me until a couple of months ago, when states suddenly starting switching from ACT to the SAT. I was poking around the internet, trying to find out more about Colorado’s abrupt and surprising decision to drop the ACT after 15 years, and I came across a couple of sources reporting that not only would rSAT replace the ACT, but it would replace PARCC as well. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Apr 6, 2016 | Blog, College Admissions, Issues in Education

If there’s one thing that everyone can agree on, it’s that college admissions is out of control. With schools posting new record-low acceptance rates each year, it’s hard not to wonder where things will end. Will Princeton soon have a 3% acceptance rate? Will Harvard dip below 2% Or, as Frank Bruni recently suggested in a satirical New York Times piece, will Stanford eventually boast that it did not accept a single student into its freshman class?

As long as students can apply to as many schools as they want with the click of a button, there’s nothing to suggest that the stampede for spots at a handful of elite schools will become any less intense; the fact that the vast majority of colleges in the United States accept over half of their applicants is no consolation to those seeking a spot at the top. With 40,000+ students clamoring for only a couple of thousands slots at places like Harvard and Stanford, and virtually no baseline criteria to deter weaker applicants, there’s no way for the process not to be stressful. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Feb 5, 2016 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

A couple of weeks ago, I posted a guest commentary entitled “For What It’s Worth,” detailing the College Board’s attempt not simply to recapture market share from the ACT but to marginalize that company completely. I’m planning to write a fuller response to the post another time; for now, however, I’d like to focus on one point that was lurking between in the original article but that I think could stand to be made more explicit. It’s pretty apparent that the College Board is competing very hard to reestablish its traditional dominance in the testing market – that’s been clear for a while now – but what’s less apparent is that it may not be a fair fight.

I want to take a closer look at the three states that the College Board has managed to wrest away from the ACT: Michigan, Illinois, and Colorado. All three of these states had fairly longstanding relationships with the ACT, and the announcements that they would be switching to the SAT came abruptly and caught a lot of people off guard. Unsurprisingly, they’ve also engendered a fair amount of pushback. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jan 18, 2016 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

For those of you who haven’t been following the College Board’s recent exploits, the company is in the process of staging a massive, national attempt to recapture market share from the ACT. Traditionally, a number of states, primarily in the Midwest and South, have required the ACT for graduation. Over the past several months, however, several states known for their longstanding relationships with the ACT have abruptly – and unexpectedly – announced that they will be dropping the ACT and mandating the redesigned SAT. The following commentary was sent to me by a West Coast educator who has been closely following these developments.

For What It’s Worth

On December 4, 2015 a 15-member evaluation committee met in Denver, Colorado to begin the process of awarding a 5-year state testing contract to either the ACT, Inc. or the College Board. After meeting three more times (December 10, 11, and 18th) the evaluation committee awarded the Colorado contract to the College Board on December 21, 2015. The committee’s meetings were not open to the public and the names of the committee members were not known until about two weeks later.

Once the committee’s decision became public, parents complained that it placed an unfair burden on juniors who had been preparing for the ACT. Over 150 school officials responded by sending a protest letter to Interim Education Commissioner Elliott Asp. The letter emphasized the problem faced by juniors and also noted that Colorado would be abandoning a test for which they had 15 years of data for a new test with no data. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 6, 2015 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

I’m not sure how I missed it when it came out, but Barry Garelick and Katherine Beals’s “Explaining Your Math: Unnecessary at Best, Encumbering at Worst,” which appeared in The Atlantic last month, is a must-read for anyone who wants to understand just how problematic some of Common Core’s assumptions about learning are, particularly as they pertain to requiring young children to explain their reasoning in writing.

(Side note: I’m not sure what’s up with the Atlantic, but they’ve at least partially redeemed themselves for the very, very factually questionable piece they recently ran about the redesigned SAT. Maybe the editors have realized how much everyone hates Common Core by this point and thought it would be in their best interest to jump on the bandwagon, but don’t think that the general public has yet drawn the connection between CC and the Coleman-run College Board?)

I’ve read some of Barry’s critiques of Common Core before, and his explanations of “rote understanding” in part provided the framework that helped me understand just what “supporting evidence” questions on the reading section of the new SAT are really about.

Barry and Katherine’s article is worth reading in its entirety, but one point that struck me as particularly salient.

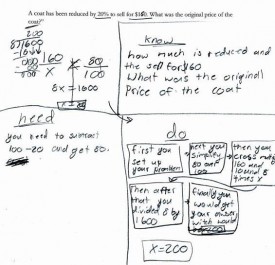

Math learning is a progression from concrete to abstract…Once a particular word problem has been translated into a mathematical representation, the entirety of its mathematically relevant content is condensed onto abstract symbols, freeing working memory and unleashing the power of pure mathematics. That is, information and procedures that have been become automatic frees up working memory. With working memory less burdened, the student can focus on solving the problem at hand. Thus, requiring explanations beyond the mathematics itself distracts and diverts students away from the convenience and power of abstraction. Mandatory demonstrations of “mathematical understanding,” in other words, can impede the “doing” of actual mathematics.

Although it’s not an exact analogy, many of these points have verbal counterparts. Reading is also a progression from concrete to abstract: first, students learn that letters are represented as abstract symbols, and that those symbols correspond to specific sounds, which get combined in various ways. When students have mastered the symbol/sound relationship (decoding) and encoded them in their brains, their working memories are freed up to focus on the content of what they are reading, a switch that normally occurs around third or fourth grade.

Amazingly, Common Core does not prescribe that students compose paragraphs (or flow charts) demonstrating, for example, that they understand why c-a-t spells cat. (Actually, anyone, if you have heard of such an exercise, please let me know. I just made that up, but given some of the stories I’ve heard about what goes on in classrooms these days, I wouldn’t be surprised if someone, somewhere were actually doing that.)

What CC does, however, is a slightly higher level equivalent — namely, requiring the continual citing of textual “evidence.” As I outlined in my last couple of posts, CC, and thus the new SAT, often employs a very particular definition of “evidence.” Rather than use quotations, etc. to support their own ideas about a work or the arguments it contains (arguments that would necessarily reveal background knowledge and comprehension, or lack thereof), students are required to demonstrate their comprehension over and over again by “staying within the four corners of the text,” repeatedly returning it to cite key words and phrases that reveal its meaning — in other words, their understanding of the (presumably) self-evident principle that a text means what it means because it says what it says. As is true for math, entire approach to reading confuses demonstration of a skill with “deep” possession of that skill.

That, of course, has absolutely nothing to do with how reading works in the real world. Nobody, nobody, reads this way. Strong readers do not need to stop repeatedly in order to demonstrate that they understand what they’re reading. They do not need to point to words or phrases and announce that they mean what they mean because they mean it. Rather, they indicate their comprehension by discussing (or writing about) the content of the text, by engaging with its ideas, by questioning them, by showing how they draw on or influence the ideas of others, by pointing out subtleties other readers might miss… the list goes on and on.

Incidentally, I’ve had adults gush to me that their children/students are suddenly acquiring all sorts of higher level skills, like citing texts and using evidence, but I wonder whether they’re actually being taken in by appearances. As I mentioned in my last post, although it may seem that children being taught this way are performing a sophisticated skill (“rote understanding”), they are actually performing a very basic one. I think Barry puts it perfectly when he says that It is as if the purveyors of these practices are saying: “If we can just get them to do things that look like what we imagine a mathematician does, then they will be real mathematicians.”

In that context, these parents’/teachers’ reactions are entirely understandable: the logic of what is actually going on is so bizarre and runs so completely counter to a commonsense understanding of how the world works that such an explanation would occur to virtually no one who hadn’t spent considerable time mucking around in the CC dirt.

To get back to the my original point, though, the obsessive focus on the text itself, while certainly appropriate in some situations, ultimately serves to prohibit students from moving beyond the text, from engaging with its ideas in any substantive way. But then, I suspect that this limited, artificial type of analysis is actually the goal.

I think that what it ultimately comes down to is assessment — or rather the potential for electronic assessment. Students’ own arguments are messier, less “objective,” and more complicated, and thus more expensive, to assess. Holistic, open-ended assessment just isn’t scalable the same way that computerized multiple choice tests are, and choosing/highlighting specific lines of a text is an act that lends itself well to (cheap, automated) electronic grading. And without these convenient types of assessments, how could the education market ever truly be brought to scale?