by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 26, 2015 | Blog, SAT Essay, The New SAT

For the last part in this series, I want to consider the College Board’s claim that the redesigned SAT essay is representative of the type of assignments students will do in college.

Let’s start by considering the sorts of passages that students are asked to analyze.

As I previously discussed, the redesigned SAT essay is based on the rhetorical essay from the AP English Language and Composition (AP Comp) exam. While they comprise a wide range of themes, styles, and periods, the passages chosen for that test are usually selected because they are exceptionally interesting from a rhetorical standpoint. Even if the works they are excerpted from would most likely be studied in their social/historical context in an actual college class, it makes sense to study them from a strictly rhetorical angle as well. Different types of reading can be appropriate for different situation, and this type of reading in this particular context is well justified.

In contrast, the texts chosen for analysis on the new SAT essay are essentially the type of humanities and social science passages that routinely appear on the current SAT – serious, moderately challenging contemporary pieces intended for an educated general adult audience. To be sure, this type of writing is not completely straightforward: ideas and points of views are often presented in a manner that is subtler than what most high school readers are accustomed to, and authors are likely to make use of the “they say/I say” model, dialoguing with and responding to other people’s ideas. Most students will in fact do a substantial amount of this type of reading in college.

By most academic standards, however, these types of passages would not be considered rhetorical models. It is possible to analyze them rhetorically – it is possible to analyze pretty much anything rhetorically – but a more relevant question is why anyone would want to analyze them rhetorically. Simply put, there usually isn’t all that much to say. As a result, it’s entirely unsurprising that students will resort to flowery, overblown descriptions that are at odds with actual moderate tone and content of the passages. In fact, that will often be the only way that students can produce an essay that is sufficiently lengthy to receive a top score.

There are, however, a couple of even more serious issues.

First, although the SAT essay technically involves an analysis, it is primarily a descriptive essay in the sense that students are not expected to engage with either the ideas in the text or offer up any ideas of their own. With exceedingly few exceptions, however, the writing that students are asked to do in college with be thesis-driven in the traditional sense – that is, students will be required to formulate their own original arguments, which they then support with various pieces of specific evidence (facts, statistics, anecdotes, etc.) Although they may be expected to take other people’s ideas into account and “dialogue” with them, they will generally be asked to do so as a launching pad for their own ideas. They may on occasion find it necessary to discuss how a particular author presents his or her evidence in order to consider a particular nuance or implication, but almost never will they spend an entire assignment focusing exclusively on the manner in which someone else presents an argument. So although the skills tested on the SAT essay may in some cases be a useful component of college work, the essay itself has virtually nothing to do with the type of assignments students will actually be expected to complete in college.

By the way, for anyone who wants understand the sort of work that students will genuinely be expected to do in college, I cannot recommend Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein’s They Say/I Say strongly enough. This is a book written by actual freshman composition instructors with decades of experience. Suffice it to say that it doesn’t have much to do with what the test-writers at the College Board imagine that college assignments look like.

Now for the second point: the “evidence” problem.

As I’ve mentioned before, the SAT essay prompt does not explicitly ask students to provide a rhetorical analysis; rather, it asks them to consider how the writer uses “evidence” to build his or her argument. That sounds like a reasonable task on the surface, but it falls apart pretty quickly once you start to consider its implications.

When students do the type of reading that the SAT essay tests in college, it will pretty much always be in the context of a particular subject (sociology, anthropology, economics, etc.). By definition, non-fiction is both dependent on and engaged with the world outside the text. There is no way to analyze that type of writing meaningfully or effectively without taking that context into account. Any linguistic or rhetorical analysis would always be informed by a host of other, external factors that pretty much any professor would expect a student to discuss. There is a reason that “close reading” is normally associated with fiction and poetry, whose meanings are far less dependent on outside factors. Any assignment that asks students to analyze a non-fiction author’s use of evidence without considering the surrounding context is therefore seriously misrepresenting what it means to use evidence in the real world.

In college and in the working world, the primary focus is never just on how evidence is presented, but rather how valid that evidence is. You cannot simply present any old facts that happen to be consistent with the claim you are making – those facts must actually be true, and any competent analysis must take that factor into account. The fact that professors and employers complain that students/employees have difficulty using evidence does not mean that the problem can be solved just by turning “evidence” into a formal skill. Rather, I would argue that the difficulties students and employees have in using evidence effectively is actually a symptom of a deeper problem, namely a lack of knowledge and perhaps a lack of exposure to (or an unwillingness to consider) a variety of perspectives.

If you are writing a Sociology paper, for example, you cannot simply state that the author of a particular study used statistics to support her conclusion, or worse, claim that an author’s position is “convincing” or “effective,” or that it constitutes a “rich analysis” because the author uses lots of statistics as evidence. Rather, you are responsible for evaluating the conditions under which those statistics were gathered; for understanding the characteristics of the groups used to obtain those statistics; and for determining what factors may not have been taken into account in the gathering of those statistics. You are also expected to draw on socio-cultural, demographic, and economic information about the population being studied, about previous studies in which that population was involved, and about the conclusions drawn from those studies.

I could go on like this for a while, but I think you probably get the picture.

As I discussed in my last post, some of the sample essays posted by the College Board show a default position commonly adopted by many students who aren’t fully sure how to navigate the type of analysis the new SAT essay requires – something I called “praising the author.” Because the SAT is such an important test, they assume that any author whose work appears on it must be a pretty big. As a result, they figure that they can score some easy points by cranking up the flattery. Thus, authors are described as “brilliant” and “passionate” and “renowned,” even if they are none of those things.

As a result, the entire point of the assignment is lost. Ideally, the goal of close reading is to understand how an author’s argument works as precisely as possible in order to formulate a cogent and well-reasoned response. The goal is to comprehend, not to judge or praise. Otherwise, the writer risks setting up straw men and arguing in relation to positions that they author does not actually take.

The sample essay scoring, however, implies something different and potentially quite problematic. When students are rewarded for offering up unfounded praise and judgments, they can easily acquire the illusion that they are genuinely qualified to evaluate professional writers and scholars, even if their own composition skills are at best middling and they lack any substantial knowledge about a subject. As a result, they can end up confused about what academic writing entails, and about what is and is not appropriate/conventional (which again brings us back to They Say/I Say).

These are not theoretical concerns for me; I have actually tutored college students who used these techniques in their writing.

My guess is that a fair number of colleges will recognize just how problematic an assignment the new essay is and deem it optional. But that in turn creates an even larger problem. Colleges cannot very well go essay-optional on the SAT and not the ACT. So what will happen, I suspect, is that many colleges that currently require the ACT with Writing will drop that requirement as well – and that means highly selective colleges will be considering applications without a single example of a student’s authentic, unedited writing. Bill Fitzsimmons at Harvard came out so early and so strongly in favor of the SAT redesign that it would likely be too much of an embarrassment to renege later, and Princeton, Yale, and Stanford will presumably continue to go along with whatever Harvard does. Aside from those four schools, however, all bets are probably off.

If that shift does in fact occur, then no longer will schools be able to flag applicants whose standardized-test essays are strikingly different from their personal essays. There will be even less of a way to tell what is the result of a stubborn 17 year-old locking herself in her room and refusing to show her essays to anyone, and what is the work of a parent or an English teacher… or a $500/hr. consultant.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 18, 2015 | Blog, SAT Essay, The New SAT

In response to my previous post on the equity issues surrounding the redesigned SAT essay, one reader had this to say:

I read a few of the essay prompts and honestly they seem like a joke. Essentially, each prompt asked for the exact same thing, it’s almost like CB is just screaming “MAKE A TEMPLATE” because all students need to do is plug in the author’s name, cite an example, and put a quote here and there and if it’s surrounded by prepared fancy sentences, they’ve got an easy 12. (or whatever it is now)

That’s a fair point. I didn’t actually mean to imply in my earlier post that students would actually need to be experts in rhetoric in order to score well – my goal was primarily to point out the mismatch between the background a student would need to seriously be able to complete the assignment, and the sort of background the most students will actually bring to the assignment.

For a good gauge of what is likely to happen, consider the French AP exam, which was revised a couple of years ago to be more holistic and “relevant.” It now includes a synthesis essay that is well beyond what most AP French students can write. The result? Score inflation. A similar phenomenon is inevitable here: when there is such a big mismatch between ideal and reality, the only way for the College Boart to avoid embarrassment and promote the illusion that students are actually doing college-level work is assign high scores to reasonably competent work that does not actually demonstrate mastery but that throws in a few fancy flourishes, and solid passing scores to work that is only semi-component.

So I agree halfway. Something like what the reader describes is probably going to be a pretty reliable formula, albeit one that many students will need tutoring to figure out. But that said, I suspect that it will be one for churning out solid, mid-range essays, not top-scoring ones. Here’s why:

While looking through the examples provided by the College Board, I noticed something interesting: out of all the essays, exactly one made extensive use of “fancy” rhetorical terminology (anecdote, allusion, pathos, dichotomy). Would you like to guess which one? If you said the only essay to earn top scores in each of the three rubric categories, you’d be right.

What this suggests to me is that the redesigned essay will in fact be vulnerable to many of the same “inflation” techniques that many high-scoring students already employ. As Katherine Beals and Barry Garelick’s recent Atlantic article discussed, the only way to assess learning is to look for “markers” typically associated with comprehension/mastery. A problem arises, however, when the goal becomes solely to exhibit the markers of mastery without actually mastering anything – and standardized test- essays are nothing if not famous for being judged on markers of mastery rather than on substance.

The current SAT essay, of course, has been criticized for encouraging fake “fancy” writing – bombastic, flowery prose stuffed full of ten-dollar words, and there is absolutely nothing to suggest that this will change. In fact, the new essay is likely to encourage that type of writing just as much, if not more, than the old one.

Indeed, the top-scoring examples include some truly cringe-worthy turns of phrase. For example, consider one student’s statement that “This dual utilization of claims from two separate sources conveys to Gioia’s audience the sense that the skills built through immersion in the arts are vital to succeeding in the modern workplace which aids in logically leading his audience to the conclusion that a loss of experience with the arts may foreshadow troubling results.”

Not to mention this: “In paragraph 5, Gioia utilizes a synergistic reference to two separate sources of information that serves to provide a stronger compilation of support for his main topic” (https://collegereadiness.collegeboard.org/sample-questions/essay/2, last example).

And this: “In order to achieve proper credibility and stir emotion, undeniable facts must reside in passage.”

This is the sort of prose that makes freshman (college) composition instructors tear their hair out. Is this what the College Board means by “college readiness?”

Furthermore, if the use of fancy terminology correlates with high scores, why not exploit that correspondence and simply pump out essays stuffed to the gills with exotic terms, with little regard for whether they describe what is actually occurring in the text? As long as the description is sufficiently flowery, those sorts of details are likely to slip by unnoticed.

In fact, why not go a step further and simply make up some Greek-sounding literary terms? Essay graders are unlikely to spend more than the current two minutes scoring essays; they don’t have the time or the liberty to check whether obscure rhetorical terms actually exist. Some really smart kids with a slightly twisted sense of humor will undoubtedly decide to have some fun at the College Board’s expense. Heck, if I could force myself to wake up at 6 a.m. on a Saturday morning, I’d be tempted to go and do it myself.

Another observation: as discussed in an earlier post, one of the key goals of the SAT essay redesign was to stop students from making up information. But even that seems to have failed: lacking sufficient background information about the work they are analyzing, students will simply resort to conjecture. For example, the writer of the essay scoring 4/3/4 states that Bogard (the author of the first sample passage) is “respected,” and that “he has done his research.” Exactly how would the student know that Bogard is “respected?” Or that he even did research? (Maybe he just found the figures in a magazine somewhere.) Or that the figures he cites are even accurate?

It is of course reasonable to assume those things are true, but strictly speaking, the student is “stepping outside the four corners of the text” and making inferences that he or she cannot “prove” objectively. So despite the College Board’s adamant insistence that essays rely strictly on the information provided in the passages, the inclusion of these sorts of statements in a high-scoring sample essay certainly suggests that the boundary between “inside” and “outside” the text is somewhat more flexible than it would appear.

The point, of course, is that it is extraordinarily difficult, if not downright impossible, to remain 100% within the “four corners” of a non-fiction text and still write an analysis that makes any sense at all – particularly if one lacks the ability to identify a wide range of rhetorical figures. Of course students will resort to making up plausible-sounding information to pad their arguments. And based on the sample essays, it certainly seems that they will continue to be rewarded for doing so.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 13, 2015 | Blog, SAT Essay, The New SAT

In my previous post, I introduced some of background issues surrounding the new SAT essay. Here, I’d like to examine to examine how the redesigned essay, rather than make the SAT a fairer test as the College Board claims, will likely provide further advantages to a small, already privileged segment of the test-taking population.

Let’s start with the fact that the new essay was adapted from the rhetorical essay on the AP English Language and Composition (AP Comp) exam.

To be sure, the colleges that require the essay are likely to draw many applicants enrolled in AP Comp as juniors, but there will still undoubtedly be tens of thousands of students sitting for the SAT essay who are not enrolled in AP Comp, or whose schools do not even offer that class. Many other students whose schools do offer AP Comp may not take it until senior year, well after they’ve taken their first SAT. And then there will be students who are enrolled in AP Comp as juniors but who spend class talking in small groups with their classmates and not ever being taught about rhetorical analysis. (Based on my own experience tutoring AP Comp, I suspect that many students fall into that last category.) What sort of value is there in asking so many students to write an essay that they are totally unprepared to write?

The College Board, of course, has attempted to make the essay appear more egalitarian by insisting that no particular terminology or background knowledge is required, and that students can find all the information they need in the passage. Whereas the AP Comp prompt explicitly asks students to analyze the rhetorical choices…an author makes in order to develop her/her argument, the College Board deliberately avoids use of the term “rhetoric” for the SAT essay, opting for the more neutral “evidence and reasoning” and stylistic or persuasive elements,” and giving the impression that the assignment is wide open by asserting that students may also analyze features of [their] own choice.

The problem is that this type of formal, written textual analysis is a highly artificial task. It involves a very particular type of abstract thought, one that really only exists in school. (I suspect that the only American students seriously studying rhetoric at a high level are budding classicists at a handful of very, very elite mostly private schools – a minuscule percentage of test-takers.) Learning to notice, to divide, to label, to categorize, to enter into a text and describe the order and logic by which it functions… These are not instinctive ways of reading; learning to do these things well takes considerable practice. If students don’t acquire this particular skill set in school, and more particularly in English class, they almost certainly won’t acquire it anywhere else. Of all the things tested on the new SAT, this is the one Khan Academy is least equipped to handle.

It also strikes me as naïve and more than a little bit misleading to insist that this type of analysis can be performed by any old student if the technical aspect is removed – that is, if students write “appeal to emotion” rather than pathos. Yes, it is possible to write a top-scoring essay that employs nothing but plain old Anglo-Saxon words, but in most cases, the students most capable of even faking their way through a rhetorical analysis will be precisely the ones who have learned the formal terms. Students don’t somehow acquire skills simply from being allowed to express themselves in non-technical language.

The choice to adopt this particular template for the SAT essay was, I imagine, based on the presumption that Common Core would sweep through classrooms across the United States, with all students spending their English periods diligently practicing for college and career readiness by combing through non-fiction passages, finding “evidence” (the text means what it means because it says what it says) and identifying “appeals to emotion and authority.”

Needless to say, that reality has not materialized; however, the SAT is based on the assumption that it would.

So whereas smart, solid writers who didn’t do much of anything in English class had as good a chance as anyone else at doing well on the pre-2016 essay, smart, solid writers who have not been given practice in this particular type of writing in English class will now be at a much larger disadvantage. There will of course be the extreme outliers who can sit themselves down with a prep book, read over a few examples, and start churning out flawless expository prose, but they will be the exceptions that prove the rule.

As for the rest, well… let’s just say the new essay is basically the College Board’s gift to the tutoring industry.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 9, 2015 | Blog, SAT Essay, The New SAT

In the past, I haven’t posted much about the SAT essay. Even though my students always did well, teaching the SAT essay was never my favorite part of tutoring, in large part because I’m what most people would consider a natural writer (thanks in large part to the 5,000 or so books I consumed over the course of my childhood), and “naturals” don’t usually make the best teachers. Besides, teaching someone to write is essentially a question of teaching them to think, and that’s probably the only thing harder than teaching someone to read.

The redesigned essay is a little different, first because it directly concerns the type of rhetorical analysis that so much of my work focuses on. In theory, I should like it a lot. At the same time, though, it embodies some of the most problematic aspects of the new SAT for me. Some of these issues recur throughout the test but seem particularly thorny here.

I’ve been trying to elucidate my thoughts about the essay for a long time; for some reason, I’m finding it exceptionally difficult to disentangle them. Every point seems mixed up with a dozen other points, and every time I start to go in one direction, I inevitably get tugged off in a different one. For that reason, I’ve decided to devote multiple posts to this topic. That way, I can keep myself focused on a limited number of ideas at a time and avoid writing a post so long that no one can get more than halfway through!

Before launching into an examination of the essay itself, some background.

First, it is necessary to understand that the major driving force behind the essay change is the utter lack of correlation between factual accuracy and scores – that is, the rather embarrassing fact that students are free to invent examples (personal experiences, historical figures/battles/act, novels, etc.) without penalty. In particular, personal examples have been a particular target of David Coleman’s ire because they cannot be assessed “objectively.” The College Board simply could not withstand any more bad publicity for that particular shortcoming. As a result, it was necessary to devise a structure that would simultaneously require students to use “evidence” yet not require – or rather appear not to require – any outside knowledge whatsoever.

As I’ve pointed out before, students have been – and still are – perfectly free to make up examples on the ACT essay, but for some mysterious reason, the ACT never seems to take the kind of flack that the SAT does. Again, marketing.

My feelings on this issue have evolved somewhat over the years; they’re sufficiently complex to merit an entire post, if not more, so for now I’ll leave my opinion out of this particular aspect of the discussion.

Let’s start with the pre-2016 essay.

Despite its very considerable shortcomings, the current SAT essay is as close as possible to a pure exercise in “using evidence” – or at least in supporting a claim with information consistent with that claim (information that may or may not be factually accurate), which is essentially the meaning of “evidence” that the College Board itself has chosen to adopt.

For all its pseudo-philosophical hokeyness, the current SAT essay does at least represents an attempt to be fair. The questions are deliberately constructed to be so broad that anyone, regardless of background, can potentially find something to say about them. (Are people’s lives the result of the choices they make? Can knowledge be a burden rather than a benefit?). Furthermore, students are free to support their arguments with examples from any area they choose – contrary to popular belief, there is ample room for creativity.

While students may, if they so choose, use personal examples, the top-scoring essays tend to use examples from literature, history, science, and current events. The example of a top-scoring essay in the Official Guide, if memory serves me correctly, is an analysis of the factors leading up to the stock market crash of 1929 – not exactly a personal narrative. In contrast, essays that rely on personal examples, particularly invented ones, tend to be vague, unconvincing, and immature. Yes, there are some students who can pull that type of fabrication off with aplomb, but in most cases, “can” does not mean “should.”

Furthermore, students who make up facts to support other types of examples are rarely able to do so convincingly. The ones who can are, by definition, strong writers who understand how to bullshit effectively – a highly useful real-world skill, it should be pointed out. But in general, the best writers tend to have strong knowledge bases (both being the result of a good education) and thus the least need to make up facts.

That is why the essay, formerly part of the Writing SAT II test, was relatively uncontroversial for most of its existence: only selective colleges required it, and so only the students who took it were students applying to selective college – a far, far smaller number than apply today. As prospective applicants to selective colleges, those-test takers were generally taking very rigorous classes and thus had very a solid academic base from which to draw. Remember that this was also in the days before work could be copied and pasted from Wikipedia, and when AP classes were still mostly restricted to very top students. While plenty of smart-alecks (including, I should confess, me) did of course invent examples, the phenomenon was considerably more limited than it became in 2005, when the essay was tacked on to the SAT-I.

Based on what I’ve witnessed, I suspect that the questionable veracity of many current essays is also a result of the reality that many students who attempt to write about books, historical events, scientific examples, etc. simply do not know enough facts to support their arguments effectively, either because they are not required to learn them at all in school (the acquisition of factual knowledge being dismissed as “rote memorization” or “mere facts”), or because information is presented in such a fragmentary, disorganized manner that they lack the sort of mental framework that would allow them to retain the facts they do learn.

One of the unfortunate consequences of doing away with lectures, I would argue, is that students are not given the sort of coherent narratives that tend to facilitate the retention of factual information. (Yes, they can read or watch online lectures, but there’s no substitute for sitting in a room with a real, live person who can sense when a class is confused and back up or adjust an explanation accordingly.)

At any rate, when word got out about just how ridiculous some of those top-scoring essays were… Well, the College Board had a public relations problem on its hands. The essay redesign was thus also prompted by the need to remove the factual knowledge component.

Now, here it gets interesting. As I forgot until recently, the GRE “analyze an argument” essay actually solves the College Board’s problem quite effectively. (The GMAT and LSAT also have similar essays.) Test-takers are presented with a brief argument, either in the form of a letter to an editor, a summary of research in a magazine or journal, or a pitch for a new business. While the exact prompt can vary slightly, it is usually something along the lines of this: Write a response in which you discuss what specific evidence is needed to evaluate the argument and explain how the evidence would weaken or strengthen the argument.

The beauty of the assignment is that it has clearly defined parameters – there is effectively no way for students to go outside the bounds of the situation described – yet allows for considerable flexibility. The situations are also general and neutral enough that no specific outside knowledge, terminology, or coursework is necessary to evaluate arguments concerning them.

In short, it is a solid, fair, well-designed task that reveals a considerable amount about students’ ability to think logically, present and organize their ideas in writing, evaluate claims/evidence, and “dialogue” with differing points of view while still maintaining a clear focus on their own argument.

There is absolutely no reason this assignment could not have been adapted for younger students. It would have eliminated any temptation for students to invent (personal) examples while providing an excellent snapshot of analytical writing ability and remaining more or less universally accessible. It also would have been perfectly consistent with the redesigned exam’s focus on “evidence.”

Instead, the College Board essentially created a diluted rhetorical strategy essay, taken from the AP English Composition exam — a very specific, subject-based essay that many students will lack prior experience writing. Students are given 50 minutes (double the current 25) to read a passage of about 750 words in response to the following prompt:

As you read the passage below, consider how the author uses

- evidence, such as facts or examples, to support claims.

- reasoning to develop ideas and to connect claims and evidence.

- stylistic or persuasive elements, such as word choice or appeals to emotion, to add power to the ideas expressed.

Write an essay in which you explain how the author builds an argument to persuade his/her audience that xxx. In your essay, analyze how the author uses one or more of the features in the directions that precede the passage (or features of your own choice) to strengthen the logic and persuasiveness of his/her argument. Be sure that your analysis focuses on the most relevant features of the passage.

Your essay should not explain whether you agree with the author’s claims, but rather explain how the author builds an argument to persuade his/her audience.

Before I go any further, I want to make something clear: I am not in any way opposed to asking students to engage closely with texts, or to analyzing how authors construct their arguments, or to requiring the use of textual evidence to support one’s arguments. Most of my work is devoted to teaching people to do these very things.

What I am opposed to is an assignment that directly contradicts claims of increased equity by testing skills only a small percentage of test-takers have been given the opportunity to acquire; that misrepresents the amount and type of knowledge needed to complete the assignment effectively; and that purports to reflect the type of work that students will do in college but that is actually very far removed from what the vast majority of actual college work entails.

In my next post, I’ll start to look at these issues more closely.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 6, 2015 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

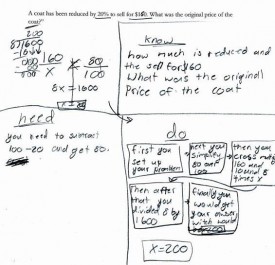

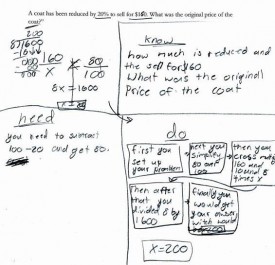

I’m not sure how I missed it when it came out, but Barry Garelick and Katherine Beals’s “Explaining Your Math: Unnecessary at Best, Encumbering at Worst,” which appeared in The Atlantic last month, is a must-read for anyone who wants to understand just how problematic some of Common Core’s assumptions about learning are, particularly as they pertain to requiring young children to explain their reasoning in writing.

(Side note: I’m not sure what’s up with the Atlantic, but they’ve at least partially redeemed themselves for the very, very factually questionable piece they recently ran about the redesigned SAT. Maybe the editors have realized how much everyone hates Common Core by this point and thought it would be in their best interest to jump on the bandwagon, but don’t think that the general public has yet drawn the connection between CC and the Coleman-run College Board?)

I’ve read some of Barry’s critiques of Common Core before, and his explanations of “rote understanding” in part provided the framework that helped me understand just what “supporting evidence” questions on the reading section of the new SAT are really about.

Barry and Katherine’s article is worth reading in its entirety, but one point that struck me as particularly salient.

Math learning is a progression from concrete to abstract…Once a particular word problem has been translated into a mathematical representation, the entirety of its mathematically relevant content is condensed onto abstract symbols, freeing working memory and unleashing the power of pure mathematics. That is, information and procedures that have been become automatic frees up working memory. With working memory less burdened, the student can focus on solving the problem at hand. Thus, requiring explanations beyond the mathematics itself distracts and diverts students away from the convenience and power of abstraction. Mandatory demonstrations of “mathematical understanding,” in other words, can impede the “doing” of actual mathematics.

Although it’s not an exact analogy, many of these points have verbal counterparts. Reading is also a progression from concrete to abstract: first, students learn that letters are represented as abstract symbols, and that those symbols correspond to specific sounds, which get combined in various ways. When students have mastered the symbol/sound relationship (decoding) and encoded them in their brains, their working memories are freed up to focus on the content of what they are reading, a switch that normally occurs around third or fourth grade.

Amazingly, Common Core does not prescribe that students compose paragraphs (or flow charts) demonstrating, for example, that they understand why c-a-t spells cat. (Actually, anyone, if you have heard of such an exercise, please let me know. I just made that up, but given some of the stories I’ve heard about what goes on in classrooms these days, I wouldn’t be surprised if someone, somewhere were actually doing that.)

What CC does, however, is a slightly higher level equivalent — namely, requiring the continual citing of textual “evidence.” As I outlined in my last couple of posts, CC, and thus the new SAT, often employs a very particular definition of “evidence.” Rather than use quotations, etc. to support their own ideas about a work or the arguments it contains (arguments that would necessarily reveal background knowledge and comprehension, or lack thereof), students are required to demonstrate their comprehension over and over again by “staying within the four corners of the text,” repeatedly returning it to cite key words and phrases that reveal its meaning — in other words, their understanding of the (presumably) self-evident principle that a text means what it means because it says what it says. As is true for math, entire approach to reading confuses demonstration of a skill with “deep” possession of that skill.

That, of course, has absolutely nothing to do with how reading works in the real world. Nobody, nobody, reads this way. Strong readers do not need to stop repeatedly in order to demonstrate that they understand what they’re reading. They do not need to point to words or phrases and announce that they mean what they mean because they mean it. Rather, they indicate their comprehension by discussing (or writing about) the content of the text, by engaging with its ideas, by questioning them, by showing how they draw on or influence the ideas of others, by pointing out subtleties other readers might miss… the list goes on and on.

Incidentally, I’ve had adults gush to me that their children/students are suddenly acquiring all sorts of higher level skills, like citing texts and using evidence, but I wonder whether they’re actually being taken in by appearances. As I mentioned in my last post, although it may seem that children being taught this way are performing a sophisticated skill (“rote understanding”), they are actually performing a very basic one. I think Barry puts it perfectly when he says that It is as if the purveyors of these practices are saying: “If we can just get them to do things that look like what we imagine a mathematician does, then they will be real mathematicians.”

In that context, these parents’/teachers’ reactions are entirely understandable: the logic of what is actually going on is so bizarre and runs so completely counter to a commonsense understanding of how the world works that such an explanation would occur to virtually no one who hadn’t spent considerable time mucking around in the CC dirt.

To get back to the my original point, though, the obsessive focus on the text itself, while certainly appropriate in some situations, ultimately serves to prohibit students from moving beyond the text, from engaging with its ideas in any substantive way. But then, I suspect that this limited, artificial type of analysis is actually the goal.

I think that what it ultimately comes down to is assessment — or rather the potential for electronic assessment. Students’ own arguments are messier, less “objective,” and more complicated, and thus more expensive, to assess. Holistic, open-ended assessment just isn’t scalable the same way that computerized multiple choice tests are, and choosing/highlighting specific lines of a text is an act that lends itself well to (cheap, automated) electronic grading. And without these convenient types of assessments, how could the education market ever truly be brought to scale?

by Erica L. Meltzer | Nov 29, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT

In my previous post, I examined the ways in which most so-called “supporting evidence” questions on the new SAT are not really about “evidence” at all, but are actually literal comprehension questions in disguise.

So to pick up where I left off, why exactly is the College Board reworking what are primarily literal comprehension questions in such an unnecessarily complicated way?

I think there are a couple of (interrelated) reasons.

One is to create an easily quantifiable way of tracking a particular “critical thinking” skill. According to the big data model of the world, things that cannot be tagged, and thus analyzed quantitatively, do not exist. (I’m tagged, therefore I am.) According to this view, the type of open-ended analytical essays that actually require students to formulate their own theses and analyze source material are less indicative of the ability to use evidence than are multiple-choice tests. Anything holistic is suspect.

The second reason – the one I want to focus on here – is to give the illusion of sophistication and “rigor.”

Let’s start with the fact that the new SAT is essentially a Common Core capstone test, and that high school ELA Common Core Standards consist pretty much exclusively of formal skills, e.g. identifying main ideas, summarizing, comparing and contrasting; specific content knowledge is virtually absent. As Bob Shepherd puts it, “Imagine a test of biology that left out almost all world knowledge about biology and covered only biology “skills” like—I don’t know—slide-staining ability.”

At the same time, though, one of the main selling points of Common Core has been that it promotes “critical thinking” skills and leads to the development of “higher-order thinking skills.”

The problem is that genuine “higher order thinking” requires actual knowledge of a subject; it’s not something that can be done in a box. But even the new SAT is being touted as a “curriculum-based test,” it can’t explicitly require any sort of pre-existing factual knowledge – at least not on the verbal side. Indeed, the College Board is very clear about insisting that no particular knowledge of (mere rote) facts is needed to do well on the test. So there we have a paradox.

To give the impression of increased rigor, then, the only solution was to create an exam that tested simple skills in inordinately convoluted ways – ways that are largely detached from how people actually read and write, and that completely miss the point of how those skills are applied in the real world.

That is, not coincidentally, exactly the same criticism that is consistently directed at Common Core as a whole, as well as all the tests associated with it (remember comedian Louis C.K.’s rant about trying to help his daughter with her homework?)

In practice, “using evidence” is not an abstract formal skill but a context-dependent one that arises out specific knowledge of a subject. What the new SAT is testing is something subtly but significantly different: whether a given piece of information is consistent with, a given claim.

But, you say, isn’t that the very definition of evidence? Well…sort of. But in the real world (or at least that branch of it not dominated by people completely uninterested in factual truth), “using evidence” isn’t simply a matter of identifying what texts say, i.e. comprehension, but rather using information, often from a variety of sources, to support an original argument. That information must not only be consistent with the claim it is used to support, but it must also be accurate.

To use evidence effectively, it is necessary to know what sources to consult and how to locate them; to be aware of the context in which those sources were produced; and to be capable of judging that validity of the information they present — all things that require a significant amount of factual knowledge.

Evidence that is consistent with a claim can also be suspect in any number of ways. It can be partially true, it can be distorted, it can be underreported, it can be exaggerated, it can be outright falsified… and so on. But there is absolutely no way to determine any of these things in the absence of contextual/background knowledge of the subject at hand.

Crucially, there is also no way to leap from practicing the formal skill of “using evidence,” as the College Board defines it, to using evidence in the real world, or at least in the way that college professors and employers will expect students/employees to use it. If you don’t know a lot about a subject, your ability to analyze – or even to fully comprehend – arguments concerning it will be limited, regardless of how much time you have spent labeling main ideas and supporting details. That is why even the most motivated students can hit the 700 wall in SAT Critical Reading, sometimes while scoring 800s in Math and Writing; there are a sufficient number of holes in their general knowledge that there’s always something they misunderstand. There is no short-term way to get around that weakness, no matter how many “main point” or “primary purpose” questions they do.

This (misc)conception of “evidence” as a strictly formal skill leads to a parody of what real-world academic inquiry actually consists of. A 16 year-old might impress her teacher by throwing around words like “discourse,” but that does not mean that her analytical abilities are in any way comparable to those of a 50-year old tenured historian with a Ph.D., a list of peer-reviewed articles, and a couple of books under her belt — not to mention a rock-solid understanding of the chronology, major players, and running debates in her particular area of specialization, as well as the ability to sit still, take notes, and listen to her colleagues speak for long stretches at a time. Yet the College Board is effectively insisting that by superficially mimicking certain aspects of the work that actual scholars do, teenagers can leapfrog over years of hard work and magically acquire adult skills. (Ever watched a high school sophomore try to complete an exercise in “historical thinking” about the Spanish conquest of the New World when she isn’t quite sure who the Amerindians were? I have, and it’s not pretty.)

In his “Common-Sense Approach to Common Core Math” series, Barry Garelick makes this point as well:

[Students] are taught to reproduce explanations that make it appear they possess understanding—and more importantly, to make such demonstrations on the standardized tests that require them to do so. And while “drill and kill” has been held in disdain by math reforms, students are essentially “drilling understanding.”

The repeated going back to the text to answer “evidence” questions serves exactly the same purpose; it gives the appearance that students are performing a sophisticated skill when in fact they’re doing nothing of the sort. The underlying issue, namely that students might not actually understand what they read because of deficiencies in vocabulary and background knowledge, is conveniently sidestepped.

I suspect that the College Board’s “skills and knowledge” slogan was created in an attempt to head off this criticism. By cannily associating (eliding) those two things, the College Board implies that it knows just what this whole education thing is really about, and that the new SAT reflects…well, all that good stuff.

Let us recall, though, that Common Core standards essentially had to consist of a series of empty formal skills slapped together and pushed through as quickly as possible in order to circumvent close investigation or pushback. Factual knowledge was an afterthought. It was never dealt with because it was politically inconvenient and could easily have led to the sort of controversy that would have deterred governors from signing on to the standards.

As a result, proponents of Common Core are left to assert that the knowledge element will somehow just take care of itself. Exactly how that is supposed to happen is never explained, but rest assured, it just will. That is how you get nonsensical articles like Natalie Wexler’s New York Times piece, “How Common Core Can Help in the Battle of Skills vs. Knowledge”. As it turns out, Wexler chairs the board of trustees at an organization called Writing Revolution… an organization that David Coleman just happens to sit on the board of. That’s quite a coincidence, is it not?