by Erica L. Meltzer | Nov 13, 2021 | Blog, IELTS

Although it is very important to make a good first impression on your examiner by writing a strong introduction to your Task 2 essay, the body paragraphs are where your overall mark will really be determined.

Body paragraphs form the substance of your essay, and so it is important that they be structured logically (Coherence and Cohesion), and in a way that allows you to respond to the question as directly and thoroughly as possible (Task Response).

Because the Writing test requires you to apply so many skills at the same time, it can be very helpful to have a standard body-paragraph “formula” that can be used for virtually any question.

Once you have determined the focus of your paragraph, each new idea can be introduced with linking device + point.

You can then discuss that point or give an example to illustrate it using no more than two additional sentences. The limit prevents repetition, over-explaining, and going off-topic.

(more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 30, 2021 | Blog, Reading (SAT & ACT), Tutoring, Tutors

Slowly but surely, I am making progress on my webinar for tutors working with struggling older readers.

After a crash course in using Zoom to record PowerPoints, numerous attempts, and much time spent finagling computer-camera angles in my office, I’ve actually managed to produce what I hope is a serviceable recording. (I was having a bad hair day in pt. 2, but I’m hoping that everyone can deal;)

There are two parts: a shorter (approx. 40 mins.) introduction part, in which I summarize some of the key issues and background information (the Simple View; the Matthew effect; the three-cueing system); and a longer recording (1:45), in which I present and demonstrate a series of short exercises based on the sequence developed by my colleague Richard McManus at the Fluency Factory in Cohasset, Mass.

Although I spend a lot of time going over the exercises, they can actually be done in about 30 mins. and can thus be split with regular test prep. I’ve also tried to actually integrate SAT/ACT-based materials into the exercises as much as possible.

I’m currently working on the materials packet (probably in the range of 70-75 pages) and will hopefully have the whole thing ready by the week of November 7th. I haven’t yet determined the overall price, but the packet will be included along with the webinar because it would be pretty ridiculous to explain all of the exercises without, you know, actually providing them. Initially, I was going to focus on the ACT since that’s the test where speed and processing issues tend to become most apparent, but because the SAT is the more popular test, I’ve integrated some material from that exam as well.

A few points: (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 9, 2021 | Blog, Issues in Education, Phonics, Tutoring, Tutors

At the beginning of the summer, after I did my series of posts for tutors who have unexpectedly found themselves working with struggling high-school readers trying to prepare for college admissions tests, I started putting together a presentation for a webinar to address the major issues at play and demonstrate some of the exercises that can be used to help remediate such students.

Alas, my summer and the beginning of my fall got hijacked by my IELTS books, followed in rapid succession by necessary updates to my GMAT, ACT English, and ACT Reading books (followed by the IELTS again).

I’m happy to announce, however, that I finally seem to be back on track and am planning to record the webinar in the next week or so, and then people can access it at their convenience. I’m also doing my best to put together an accompanying materials pack that includes all the exercises covered. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 4, 2021 | Blog, IELTS

The print version of my IELTS grammar and vocabulary guide covering both Academic and General Training is now available on Amazon as well as the Books page. If you’re studying for that exam, or are a tutor who prepare students for it, here is what you need to know.

IELTS® Writing: Grammar and Vocabulary is based on a simple premise: to write a good essay, one must first be able to write well at the sentence level.

Many IELTS Writing guides focus on overall essay organization and construction and treat grammar and sentence-structure almost as an afterthought. And if they do emphasize these aspects of English, they often include example sentences that are much simpler than those required by the exam, or that are not fully relevant to the kinds of topics it involves. As for books written by non-native English speakers… well, I’m not even going to go there.

This is book is different. To the greatest extent possible, it focuses on direct application to the IELTS. It shows how specific structures are particularly suited to certain topics and scenarios, and points out traps to avoid. It also walks readers through the process of constructing “complex” sentences without losing control of their writing, and covers common errors that many test-takers do not even realize can easily (and quickly) prevent them from achieving their desired score. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jul 24, 2021 | ACT Reading, Blog

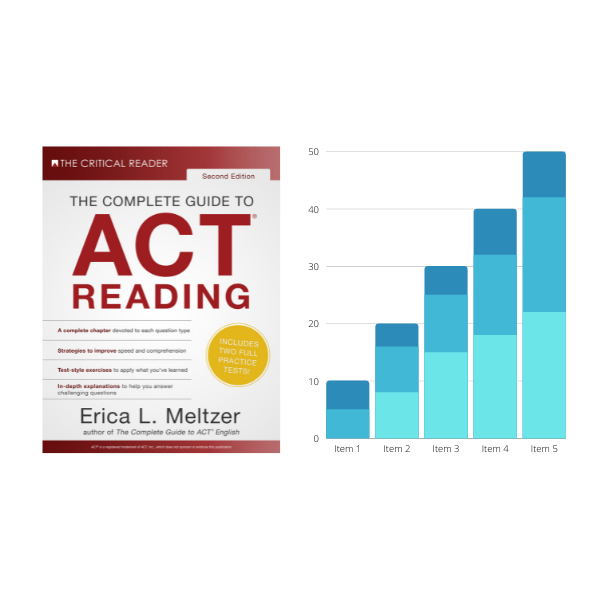

As you may have heard, the ACT is tweaking its Reading test to include some graph- or chart-based questions similar to those on the Science test and the SAT Reading test. I’ve received several inquiries regarding these changes, so I wanted to let everyone know where things stand in terms of my materials.

First, yes, I will be updating The Complete Guide to ACT Reading, although not immediately.

Unfortunately, the 2021-22 ACT Official Guide does not include any sample passages accompanied by the new question type; as of July 2021, the only example I’ve been able to locate is the one posted on the ACT website, and, well… It doesn’t seem particularly well done (to put things diplomatically). In the absence of any material from administered tests, there’s also no way for me to tell how well it reflects what the actual exam will look like. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jun 3, 2021 | Blog, Grammar (SAT & ACT), IELTS

There are three main types of conjunctions in English. Some words in different categories have identical meanings, but they have different grammatical functions. As a result, they are punctuated differently when used to begin a clause or sentence.

Although the conjunctions discussed below may also appear in the middle or at the end of a sentence in certain contexts, this post concerns their placement at the start of a sentence or clause only.

1) Coordinating Conjunctions (“FANBOYS”)

There are seven coordinating conjunctions, known collectively by the acronym FANBOYS:

These words are placed in the middle of a sentence to join two independent clauses and should follow a comma. Although the punctuation is often omitted in everyday writing, you should make an effort to use it because the comma serves to clearly separate the parts of the sentence and helps the reader follow your ideas more easily. (more…)