by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 27, 2015 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

Passage 1 is excerpted from a speech about the Common Core State Standards given by David Coleman at the senior leadership meeting at the University of Pittsburgh’s Institute of Learning in 2011. Passage 2 is from Sandra Stotsky’s June 2015 Testimony regarding Common Core, delivered at Bridgewater State University. Stotsky was a member of the Common Core validation committee who, along with R. James Milgram, refused to sign off on the Standards. Student Achievement Partners is a company founded by David Coleman that played a significant role in developing Common Core.

Passage 1

Student Achievement Partners, all you need to know about us are a couple of things. One is that we’re composed of that collection of unqualified people who were involved in developing the common standards. And our only qualification was our attention to and command of the evidence behind them. That is, it was our insistence in the standards process that it was not enough to say you wanted to or thought that kids should know these things, that you had to have evidence to support it, frankly because it was our conviction that the only way to get an eraser into the standards room was with evidence behind it, ‘cause otherwise the way standards are written you get all the adults into the room about what kids should know, and the only way to end the meeting is to include everything. That’s how we’ve gotten to the typical state standards we have today. (Mercedes Schneider, Common Core Dilemma, 2015, p. 2440 Kindle ed.) (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 19, 2015 | Blog, Issues in Education

On the surface, everyone’s favorite buzzword certainly seems unobjectionable enough. In addition to being short, snappy, and alliterative (all good qualities in a buzzword), who could possibly argue that high school students shouldn’t be prepared for college and careers? When you consider the slogan a bit more closely, however, it starts to make a little less sense.

First and most obviously, the American higher education system is staggeringly diverse, encompassing everything from for-profit trade schools to community colleges to state flagship institutions to the Ivy League. While it seems reasonable to assume that there is a baseline skills that all (or most) students should be expected to graduate from high school, a one-size-fits-all approach makes absolutely no sense when it comes to college admissions.

Does anyone seriously think that a student who wants to study accounting at a local community college and one who wants to study physics at MIT should come out of high school knowing the same things? Or that a student who wants to study communications through an online, for-profit college and a student who wants to study philosophy at Princeton should be expected to read at the same level? A student receiving straight A’s at one institution could easily need substantial remediation to even earn a passing grade at the other. Viewed this way, the definition of “college readiness” as “knowledge and skills in English and mathematics necessary to qualify for and succeed in entry-level, credit-bearing post-secondary coursework without the need for remediation” is effectively meaningless.

Second, let’s consider the “career readiness” part. Perhaps this was less true when the slogan was originally coined (by the ACT…I think), but today it is more or less impossible to obtain even the lowest-level white collar position without a college diploma. Virtually anyone entering the job market immediately after high school will almost certainly be considered only for service jobs (flipping burgers, stocking shelves at Walmart) or manual labor. While these jobs do require basic literacy and numeracy skills, they are light years away from those required by even a relatively un-challenging college program. It makes no sense to group them with post-secondary education.

Third, the pairing of “college and career” is more than a little problematic. While there are obviously some skills that translate well in both the classroom and in the boardroom (writing clearly and grammatically, organizing one’s thoughts in a logical manner, considering multiple viewpoints), there are other ways in which the skills valued in the classroom (searching for complexity, “problematizing” seemingly straightforward ideas) are exactly the opposite of those usually prized in the working world. They are enormously valuable skills, but on their own merits. It really only makes sense to lump college and work together in this way if you are attempting to redefine college as quasi-trade school for the tech industry.

Like most people, though, I assumed that the “college” part was intended refer to traditional, four-year institutions. Then, while reading one of the white papers released by Ze’ev Wurman and Sandra Stotsky (one of the writers of the 1998 Massachusetts ELA standards, considered the most rigorous in the country, and one of only two members of the Common Core validation committee to refuse to sign off on the standards), I came across this edifying tidbit:

The clearest statement of the meaning of [college and career readiness] that we have found appears in the minutes of the March 23 meeting of the Massachusetts Board of Elementary and Secondary Education. Jason Zimba, a member of the mathematics draft-writing team who had been invited to speak to the Board, stated, in response to a query, that “the concept of college readiness is minimal and focuses on non- selective colleges.” Earlier, Cynthia Schmeiser, president and CEO of ACT’s Education Division, one of Common Core’s key partners, testified to a U.S. Senate Committee that college readiness was aimed at such post-secondary institutions as “two- or four-year colleges, trade schools, or technical schools.” These candid comments raise professional and ethical issues. The concept is apparently little more than a euphemism for “minimum competencies,” the concept that guided standards and tests in the 1980s, with little success in increasing the academic achievement of low-performing students…

Moreover, it seems that this meaning for college readiness was intended only for low-achieving high school students who are to be encouraged to seek enrollment in non-selective post-secondary institutions. Despite its low academic goals and limited target, this meaning for college readiness was generalized as the academic goal for all students and offered to the public without explanation. (Stotsky and Wurman, “The Emperor’s New Clothes: National Assessments Based on Weak “College and Career Readiness Standards,” 2010.)

Stotsky goes on to point out that not a single detail from the very explicit standards laid out in the 2003 report “Understanding University Success” — a report that included input from 400 faculty members from 20 institutions, including Harvard, MIT, and the University of Virginia — was included in the Common Core Standards.

In contrast, Common Core standards were primarily written by 24 people, many of whom were affiliated with the testing industry, and some of whom had no teaching experience whatsoever. As Mercedes Schneider points out, Jason Zimba, the lead writer of the math standards:

…acknowledge[d] that ending with the Common Core in high school could preclude students from attending elite colleges. In many cases, the Core is not aligned with the expectations at the collegiate level. “If you want to take calculus your freshman year in college, you will need to take more mathematics than is in the Common Core.”

Likewise, I would add that analytical skills a tad more sophisticated than simply comparing and contrasting, or using evidence to support one’s arguments, are a prerequisite for doing any sort of serious university-level work in the humanities or social sciences. As is vocabulary beyond the level of synthesize and hypothesis.

Food for thought, the next time you hear/see Common Core described as a set of “more rigorous” (hah!) standards designed to prepare students for colleges and the workforce.”

Cynthia Schmeiser, incidentally, now works for the College Board. It’s amazing how, when you do a little prodding (or, should I say, “delve deep,” to invoke another preferred euphemism), the same names keep cropping up over and over again…

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 14, 2015 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

Carol Burris weighs in on the suggestion that the recent decline in SAT scores is due a more diverse pool of test-takers:

From the Washington Post:

Since 2011, average SAT scores have dropped by 10 points even though the proportion of test takers from the reported economic brackets has stayed the same and the modest uptick in the number of Latino students was partially offset by an increase in Asian American and international students [who have higher than average scores]. And in the year of the biggest drop (7 points), the proportional share of minority students is the same as it was in 2014. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 10, 2015 | ACT Essay, Blog

For this final part of the “writing the new ACT essay series,” we’re going to look at what is probably the most challenging aspect of writing the essay: the counterargument.

For those of you unfamiliar with the term, a counterargument is simply a perspective that refutes your main argument. Simply put, if you’re arguing that technology does more good than harm, the counterargument is that technology does more harm than good.

Before we look at an example, there are a couple of things I’d like to point out: first, I cannot stress how important transitions are in writing effective counterarguments. Without them, your reader will have no way of following your train of thought and will find it very difficult – if not impossible – to distinguish between which ideas you agree with and which ideas you disagree with.

Another key element of good counterarguments is the concession – that is, the acknowledgement that some aspects of the opposing argument are valid. This is the most unfamiliar aspect of counterarguments for many students – isn’t the whole point of a counterargument to “disprove” the opposing argument?

Ultimately, yes, the goal is to show why your argument wins out. That said, the point of a concession is to demonstrate that you’ve thought about an issue carefully, in a nuanced way rather than in straightforward black/white, good/bad terms. When presented clearly, this type of consideration actually strengthens your argument.

You can use this general template to create a counterargument:

According to Perspective x, _______________________. On one hand,

-it is true that _______________________.

-this claim has some merit because _______________________.

-the claim that _______________________ does have some validity.

On the other hand,

-this perspective fails to consider that _______________________.

-this claim overlooks the fact that _______________________.

Let’s see how this would play out in a sample paragraph that uses a personal example (yes, those are still fine). It doesn’t use the template exactly, but it’s pretty close.

Again, we’re going to use the sample prompt released by the ACT. For the purpose of this exercise, we’re only going to look at one of the perspectives; trying to work with more than that would be too confusing. In fact, you should generally avoid integrating more than one outside perspective per paragraph, unless you are a stellar writer who is already comfortable with this type of back-and-forth.

(Abridged) prompt: Automation is generally regarded as a sign of progress, but what is lost when we replace humans with machines? Given the accelerating variety and presence of intelligent machines, it is worth examining the implications and meanings of their presence in our lives.

Perspective 1: What we lose with the replacement of people with machines is some part of our humanity. Even our mundane encounters no longer require from us respect, courtesy, and tolerance for other people.

Thesis: Technology should be seen as a force for good because it creates new possibilities for people as well as a more prosperous society.

1) Topic sentence: introduce your argument (1 sentence)

Over the past few decades, new forms of technology have created ways for people communicate with one another more quickly and easily than ever before.

2) Elaborate on your argument, and provide a specific example (2-3 sentences)

From Skype to iphones apps to Facebook, technology erases borders, allowing us to talk to people halfway around the world as if they were in the next room. I have personally benefitted enormously from these technologies: my family immigrated to the United States from China when I was 6 years old, and over the past decade, gathering around the computer to chat with my grandparents and my aunt in Beijing has become a weekly ritual. Although I am sorry that we no longer live next door to them, as we did when I was little, I am nevertheless grateful to be able to see their faces and keep them updated on the details of my daily life – something that would be impossible without “smart” machines.

3) Introduce outside perspective: 1-2 sentences

Not everyone is so enthusiastic about the effects of new technologies, however. Perspective 1 offers a typical complaint, namely that the replacement of people with machines “causes us to lose some part of our humanity.”

4) Acknowledge that the perspective isn’t entirely wrong, and explain why (2-3 sentences)

On one hand, this complaint does have some merit. Walking down the street or sitting on the subway, I am often struck by the sheer number of people staring glassy-eyed into their phones. Sometimes they are so busy texting that they nearly bump into others, demonstrating a clear lack of courtesy and tolerance (notice how this statement weaves the viewpoint naturally into the writer’s argument).

5) Transition back to your argument and reaffirm it (3-4 sentences)

On the other hand, though, the benefits of technology far outweigh an occasional unpleasant sidewalk encounter – at least from my perspeective. Rather than isolate me from the world (notice how this statement indirectly refutes the counterargument), “smart” technology has served primarily to facilitate my relationships with others, not to replace them.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 10, 2015 | ACT Essay, Blog

After providing an overview of the new ACT essay and some possible approaches to it in my previous post, I want to now discuss one particular – and very important – skill involved in writing it: incorporating other perspectives into your own argument for support.

If you’ve ever written a research paper, you probably have some experience integrating the ideas of people you agree with into your writing. (And if you haven’t, you’ll get an introduction to doing so in this post.) That said, I find that most high schools do not explicitly teach students to weave supporting quotations, ideas, etc. fluidly into their writing. The quotes are there, but they’re often integrated awkwardly into the larger argument.

Very often, students assume that they do not really need to spend time introducing or explaining their quotes because they seem so self-explanatory. They’re there to support the argument, and if the argument is clear, then the point of the quotation is obvious…right? Well, not always.

The problem is that analytical writing requires much more explanation than might seem necessary. Generally speaking, people write about topics with which they are familiar. Because they know a lot of about their topics, they are often unaware of the gaps in other people’s understanding. As a result, it simply does not occur to them how explicit they need to be, and they end up inadvertently leaving out information that is necessary to understanding their thought process.

When you explain an idea – any idea – in writing, you must take your reader by the hand, so to speak, and lead them through each step of your thinking process so that they do not get lost. Introducing other people’s words or ideas in such a way that makes clear the relationship between your argument and theirs is a key part of that process. Otherwise, it’s as if you’ve skipped ahead a few steps, leaving the reader to stop and try put together the pieces. If there’s one thing you don’t want to do to your reader, it’s make your ideas hard to follow. That goes for school, the ACT, and any other writing you might do for the next sixty or seventy years.

Once again, we’re going to work with the sample prompt released by the ACT. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 8, 2015 | ACT Essay, Blog

For those of you unacquainted with it, the pre-September 2015 version of the ACT essay asked students to weigh in on a straightforward, usually high-school/teenager related question, e.g. “Should students have to maintain a C average in order to get their driver’s license,” or “Should schools establish a dress code?” Although the ACT was always pretty clear about the fact that a counterargument was necessary for a top score, it was traditionally possible to write the essay without taking one into account.

Now that’s no longer the case.

If you take the ACT with writing now, you will be given a prompt presenting a topic, then asked to consider three different viewpoints. You can write a straightforward agree/disagree thesis in response to one of the viewpoint (the simplest way to go) or fashion an original thesis based on one or more of the viewpoints (more potential for complication).

Regardless of which one you choose, you must take each of the views into account at some point in your essay.

(Click here for a sample prompt, or see below, and here for sample essays).

In comparison to the old ACT essay, the new one certainly looks more complicated: rather than one single question, there are now three separate perspectives to contend with. There’s a lot of information to absorb, analyze, and write about in a very short period.

In fact, the new ACT essay is essentially a synthesis essay, much like the one on the AP English Comp exam; the various viewpoints are simply presented in condensed form because of the 40-minute time limit.

If you’re a senior retaking the ACT and took the AP Comp test (or the AP French/Spanish/Italian language test) last year, you have a leg up because you have some experience integrating multiple arguments into your writing. If you’re a junior writing this type of essay for the first time, however, it can seem a little overwhelming.

Having tutored three out of those four exams, I’ve learned to explain some things upfront.

The most important one is that the primary focus of a synthesis essay should still be your argument. The requirement that you consider multiple perspectives does not alter that fact. Rather, your job is to talk about those various perspectives in relation to your own point of view. You can, therefore, think of the ACT essay as a standard, thesis-driven essay, just one in which you happen to discuss ideas other than your own. Your thoughts stay front and center.

Instead of viewing the various perspectives as something to make your task more complicated, think of it the opposite way: those perspectives are giving you material to work with so that you don’t have to come up with all the ideas on your own. They’re actually making your job easier.

To simplify things, you should initially take the various perspectives into account only as aids for determining your own point of view. Once you’ve come up with a clear thesis, you can then go back and work the different perspectives into your outline. To keep things simple again, focus on discussing one perspective (agree/disagree) in each paragraph; if you start to bring in too many ideas at once, you’ll most likely get lost.

I also cannot stress how important it is to spend a few minutes outlining. Don’t worry about getting behind — this is time well spent. For most people, the biggest difficulty in writing this type of essay is keeping the thread of their own argument and not getting so sidetracked by discussions of other people’s ideas that it becomes difficult to tell what they actually think. When you’re learning to write about other people’s ideas, this is the rhetorical equivalent of a tightrope walk. If you know where your argument is going from the beginning (and even have topic sentences that continually pull it back into focus, should it start to drift off in the course of a paragraph), you’re far more likely to stay on track.

If, on the other hand, you just start to write, there’s a pretty good chance your writing will either become repetitive or start to wander eventually, making it difficult for your readers to figure out just what you’re actually arguing.

Let’s look at an example of an outline based on the sample prompt released by the ACT.

(Abridged) prompt: Automation is generally regarded as a sign of progress, but what is lost when we replace humans with machines? Given the accelerating variety and presence of intelligent machines, it is worth examining the implications and meanings of their presence in our lives.

Perspective 1: What we lose with the replacement of people with machines is some part of our humanity. Even our mundane encounters no longer require from us respect, courtesy, and tolerance for other people.

Perspective 2: Machines are good at low skill, repetitive, jobs, and at high speed, extremely precise jobs. In both cases, they are better than humans. This efficiency leads to a more prosperous and progressive world for everyone.

Perspective 3: Intelligent machines challenge our longstanding idea of what humans are and can be. This is good because it pushes humans and machines toward new possibilities.

Thesis: While machines have enormous power to make our lives easier and more efficient, we must be careful not to become so dependent on them that we compromise our humanity.

Outline

I. Intro: increasing reliance on machines, 20-21st c.

II. Support: machines make life easier

-Ppl injured, increase mobility, lead normal lives

-Perspective 3

III. Against : too dependent = bad b/c texting, ignore ppl/physically present

– personal ex.

-Perspective 1

IV. Against: too dependent = bad b/c human oversight important f/work

-Work example: manufacturing high-tech parts

-Perspective 2

V. Conclusion: dangers of over reliance on machines, where are we going?

Notice a few things about this outline:

1) The organization of the essay matches the organization of the thesis (advantages, then disadvantages). This is not the only possible organization — you could just as easily discuss the disadvantages in the first two body paragraphs, then the advantages in the third — but it does save you some time in terms of trying to decide to arrange things.

2) Each paragraph focuses on one idea and integrates one outside perspective, preventing you from trying to tackle too many ideas at once and making it difficult for the reader to follow your argument.

3) Words are abbreviated in order to save time. The goal is to be just specific enough to keep yourself focused.

Next, see Part 2 of this series, which covers how to discuss supporting ideas and weave quotations smoothly into your arguments.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 7, 2015 | Blog

From Bloomberg:

Students in the high school class of 2015 turned in the lowest critical reading score on the SAT college entrance exam in more than 40 years, with all three sections declining from the previous year. Meanwhile, ACT Inc. reported that nearly 60 percent of all 2015 high school graduates took the ACT, up from 49 percent in 2011. (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-09-03/students-bombed-the-sat-this-year-in-four-charts)

Oh well, good thing the new SAT is right around the corner. Without all those obscure words and irrelevant passages, scores should start to artificially increase stabilize.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 6, 2015 | Blog, College Admissions

I don’t wade into the waters of college essays very often, but for those of you who are thinking about starting them or are already in the process of writing them, I’m going to offer some tips regarding things to avoid.

While the most effective college essays do tend to share some general features (specific, stylistically varied, have a clear story arc, are unique to the writer), they come in so many different varieties that there is no real formula to writing one. For that reason, I find it difficult to prescribe a particular set of “do’s.”

Ineffective essays, on the other hand, tend to exhibit a much clearer set of characteristics.

So having said that, I’m going start with one very big cliché to avoid: (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 3, 2015 | SAT Reading

Note: this article is part of a two-part series. See also this post, which covers the multiple-choice grammar section.

1) Take a moment to understand the question before you jump to eliminate any answers

This is especially true when a question is worded in a complex/confusing way. High scorers often lose points because they don’t take a few seconds to think about what complicated questions are really asking. As a result, they are either unsure of what they’re looking for, or thinking in the wrong “direction” when they go to look to look at the choices. Then they get confused.

Good rule of thumb: if you find yourself saying “Huh?” after you read a question or answer, you need to take a few moments and clarify.

2) Keep moving through the passages – and the questions

Reading and re-reading confusing sections of a passage is one of the biggest causes of time problems. If you find yourself starting to loop over the same section, you must resist the temptation to reread over and over again. That section might only be relevant to a single question – or no questions at all. If you spend a lot of time on it, you’re likely to end up rushing later in the section and losing easy points.

As you work through the questions, you should be doing something – anything – to work toward the answers at all times. If you’re so confused that you can’t even figure out how to start working through a question, leave it and move on. You won’t get the answer by sitting and staring. Very rarely do high scorers have time problems because they’re spending too much time on every question. More often it’s a couple of questions that drain all their time. If you’re spot-on everywhere else, you can afford to guess on a question or two; you cannot afford to rush and get two or three questions wrong per set. Figure out where your weak spots are, and learn to work around them.

As a general rule, you should spend the minimum amount of time possible on easy questions while still working carefully enough not to make any careless errors. Your goal is to leave yourself as much time as possible to work through the hardest questions.

3) Do not EVER eliminate an answer because it confuses you

I’ve said it before, but I’ll say it again. There is absolutely no relationship between your understanding of an answer and whether that answer is right or wrong. If you’re not sure about an answer, leave it.

4) Be willing to go back and forth between the question and the passage multiple times

The answer will most likely not reveal itself to you if you just sit and look at the choices. You may need to go back and forth between the question and the passage four or five times, checking one specific thing out at each go. Do not – I repeat, do not – rely on your memory.

5) Read before/after the line references

A line reference tells you where a particular word or phrase is located – it does not tell you where the answer is. The answers could be in the lines cited, or it could be before/after. If you’ve understood the question and the section of the passage referenced, and still can’t find the answer, there’s a good chance you’re looking in the wrong spot.

If you’re dealing with a function/purpose question, there’s about a 50% chance the answer won’t be in the exact lines cited, but regardless of the question type, do not ever start or stop reading in the middle of a sentence.

Likewise, if you’re asked about something close the beginning/end of a paragraph, back up or read forward as necessary. Main ideas are usually at the beginnings/ends of paragraphs – when in doubt, focus on them.

6) Answer questions in your own words

If you’re a strong reader, spot an answer immediately, and are 100% certain it’s right, it’s fine to pick it and move on. When things are less clear-cut, however, it would strongly behoove you to get a general idea of what information the correct answer will contain, keeping in mind that it might be phrased in a very different way from the way you’d say it. Even doing something as simple as playing positive/negative can make the right answer virtually pop out at you.

To reiterate: you cannot rely on the answers already there 100% of the time. They are there to sound plausible, even if they’re no such thing. Defend yourself.

7) Practice keeping calm when you don’t know the answer right away

If you stand a serious chance of scoring an 800, there’s a good chance that you’re pretty good at recognizing correct answers. There’s also a pretty good chance that most of the questions you’re getting wrong are the ones you aren’t sure about in the first place. When this is the case, one of the biggest challenges tends to involve managing your reactions when you encounter questions you aren’t sure about right away. This might only happen three or four times throughout the test, but that’s enough to cost you.

From what I’ve observed, many students who fall into this category have a tendency to freeze, then panic, then guess. Learning to keep calm is a process; you have to practice it when you’re studying in order for the there to be any chance of your doing it during the actual test.

Stop, take a moment, re-read the question calmly, and make sure you’re crystal clear on what it’s asking. Once, you’ve fully processed what you’re being asked, you can probably get rid of an answer or two. As you work through the question, you might find yourself getting a clearer idea of what it’s asking for. If you don’t, pick one specific aspect of each remaining answer to check against the passage. If you’re stuck between a general and a specific answer, start with the more specific one.

When you go back to the passage, pay attention to strong language and major transitions and “interesting” punctuation (however, therefore, but, colons, questions marks) since key information tends to be located right around them. If you’re unsure about what you’re looking for, focusing on these elements can make you suddenly notice things you missed the first time around.

8) Be willing to reconsider your original assumption

Sometimes you’ll understand a question, answer it in your own words, look at the answer choices… and find absolutely nothing that fits. When this happens, you must be willing to accept that the answer is coming from an unexpected angle, back up a couple of steps, and re-work through it from a different standpoint.

Reread the question carefully, make sure you haven’t overlooked something, get rid of answers that are clearly way off, and look at the remaining options anew.

9) Ask yourself what you’re missing

When you can’t figure out the answer, you must be willing to turn things back on yourself and ask yourself what it is you’re not seeing. Thoughts that start with, “But I think that the author is saying xxx…” will not get you to the answer. If you’ve understood the question and the answers and can’t connect one to the other, the answer must be coming from an angle you haven’t considered. You might need to read more literally, or you might have to consider an alternate meaning of a word. Embrace that fact, because fighting the test won’t change it.

10) Remember that the SAT can break its own “rules”

It’s undoubtedly a good idea to know some of the more common patterns of the test, e.g. “extreme” answers are usually wrong. If you’re seriously shooting for an 800, though, you must be willing to consider that on very rare occasions, there are exceptions. Sometimes the correct answer may include a word like always or never. You must find a balance between using the patterns of the test to your advantage and not getting so stuck on them that you let them override what’s actually going on in the passage.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 1, 2015 | Blog, Grammar (SAT & ACT)

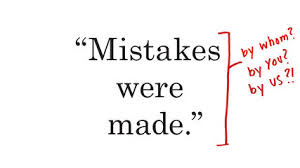

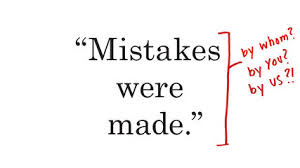

Although I can be a stickler for grammar (a tendency that I do my best to keep in check in non-teaching/blogging/grammar book-writing) life), there are nevertheless a handful of “rules” that I really and truly could not care less about. Among them are split infinitives (a ridiculous attempt to treat English like a purely Latin-based language that fails to take its Germanic roots into account); the use of “they” to refer to a singular noun when gender is not specified (no, “he” is not actually neutral, and seeing it used that way increasingly feels like an anachronism); and the prohibition against the passive voice.

The passive voice, in case you’re unfamiliar with the term, involves flipping the subject and object of a sentence around to emphasize that an action was performed by someone/something, e.g “The man drank the water,” becomes “The water was drunk by the man.” It is also possible to omit the “by” part and simply say “The water was drunk,” the implication clearly being that it was drunk by someone.

On the SAT and the ACT, answers that contain passive constructions are almost always wrong, if for no reason other than that they tend to be unnecessarily wordy and awkward. And in fact, passive constructions are by definition wordier than active ones. The awkward part… Well, that’s up for debate.

The use of the passive voice is an issue that blurs the line between grammar and style; there are instances in which the passive creates wordy, awkward horrors, but there are also cases in which it is useful to create a particular emphasis. For example, most people would never even be tempted to say “The car keys were lost by my mother.” On the other hand, it sounds perfectly normal to say “The bill was passed by Congress yesterday” — the emphasis is on the fact that the bill went through.

I always assumed that the “no passive” rule was simply something that had been cooked up a couple of centuries ago by linguistic purists (much like the “no split infinitives rule”) and handed down from masters to disciples through the ages. In this case, however, “through the ages” means more like “since the 1950s,” more specifically since the popularization of The Elements of Style.

Now, I confess to having a soft spot for Strunk and White’s chef d’oeuvre. It was the first grammar book I used in high school English class (we were handed copies in September and instructed to memorize it — progressive education this was not), and it introduced me to all sorts of wonders like non-essential clauses and the requisite semicolon before “however” at the start of a clause.

As I recently discovered, though, Strunk and White got some things wrong. As is, major, big-time, crash and burn wrong. (In my own defense, I haven’t looked at the book in years). I knew that some people had “issues” with the “little book” — to put it diplomatically — but I always wrote that off as a matter of personal taste. Then, a couple of days ago, I stumbled across Geoffrey Pullum’s delightfully titled Chronicle Review article “Fifty Years of Stupid Grammar Advice,” in which the author takes it upon himself to enumerate the ways in which Strunk and White managed to mangle their explanation of the passive voice. Indeed, they barely understood it themselves.

As Pullum points out:

What concerns me is that the bias against the passive is being retailed by a pair of authors so grammatically clueless that they don’t know what is a passive construction and what isn’t. Of the four pairs of examples offered to show readers what to avoid and how to correct it, a staggering three out of the four are mistaken diagnoses. “At dawn the crowing of a rooster could be heard” is correctly identified as a passive clause, but the other three are all errors:

- “There were a great number of dead leaves lying on the ground” has no sign of the passive in it anywhere.

- “It was not long before she was very sorry that she had said what she had” also contains nothing that is even reminiscent of the passive construction.

- “The reason that he left college was that his health became impaired” is presumably fingered as passive because of “impaired,” but that’s a mistake. It’s an adjective here. “Become” doesn’t allow a following passive clause. (Notice, for example, that “A new edition became issued by the publishers” is not grammatical.)

I’ve heard horror stories about college students getting marked down on papers because their TAs/professors mistakenly thought they had used the passive voice when that was not the case at all. (And at any rate, no one should get marked down just for using the passive voice.) It’s always a problem when people have knee-jerk reactions to concepts they don’t fully understand.

To be clear, though, I understand the pushback against the passive, especially on standardized tests. Standardized tests are, by nature, crude tools; their goal is to touch on the most common and misuses of various structures. I’ve read enough wordy, repetitive, marginally coherent SAT/ACT essays to last a lifetime, and given that experience, I don’t have a problem with the tests’ perhaps overzealous approach. In this case, however, know that the rule is a little more flexible in real life. But try not to go crazy, or a hard time will undoubtedly be had by your readers.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 1, 2015 | Blog, SAT Reading

I recently came across an inquiry from someone using the The Critical Reader to study for the SAT. The student in question had been getting all the exercise questions right in the book itself, but when he took full practice tests, he started making mistakes. How should he proceed?

While I don’t know exactly what was happening when the student took those tests, I can wager a pretty good guess.

Because The Critical Reader is organized by question type, each set of exercises focuses on a particular concept and follows a chapter focusing on that same concept. Not only is the strategy information is still pretty fresh for most people when they look at the questions, but they already know what concept every question will be testing.

When they go to take a practice test, however, that scaffolding is suddenly taken away. All the question types are mixed up together, and there’s no predicting what will come next. In addition, it is necessary to recall many different strategies and nuances of the test in rapid sequence, without any prompting about which ones are necessary. That’s a big strain on working memory. Most likely, the student was simply reading the questions and choosing answers without really considering what category each question fell into and what sort of approach would be required to answer it most effectively.

So if you find yourself in a similar situation, here’s my advice: You essentially have to create a bridge between the book and the test. Choose a couple of Reading sections and don’t worry about time. Go through each question and label it with its category (function, tone, inference, etc.).

Now, before you do each question, stop and review the strategy you need for it, e.g. remind yourself to read before and after the line reference for function questions, play positive/negative, and remember to mark off all the “supporting evidence” pairs.

Work this way for a couple of sections, or even a full test — however long it takes for the process to become more automatic. The goal is to practice identifying which strategies are necessary and get used to applying them when no one (me) is holding up a sign telling you what to look for.

When the process feels more automatic, take a timed test and see what holds. Then repeat as necessary.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 29, 2015 | ACT English/SAT Writing

If you google “perfect score on SAT writing” (or “perfect score on ACT English”) you’ll probably come up with a couple dozen hits that make it seem as if accomplishing that feat is merely a matter of learning a few simple rules.

Now, if you have an outstanding ear and a solid basic knowledge of grammar, that could indeed be the case. And to be sure, the SAT and ACT both test a limited number of concepts (somewhere between 10 and 20, depending on how you count) over and over again, in very predictable ways. Within those 10-20 rules, however, there are many variations, and it’s always possible for rules to be tested or combined in slightly new ways. And rules that initially seem simple and straightforward can have very challenging applications.

Passages frequently mention topics, individuals, and places that most students aren’t particularly familiar with. It can be hard to worry about subject-verb agreement when you’re trying to puzzle through sentences that refer to multi-syllabic chemical compounds.

Given that, I’ve decided to compile a different sort of list. It is not a list of rules tested on the multiple choice grammar portion of the SAT and the English portion of the ACT. You can find those in my complete list of SAT and ACT grammar rules. Rather, it is a list of skills that you must have in order to apply those rules effectively.

1) Recognizing prepositions and prepositional phrases

Prepositions are “location” and “time” words such as to, of, by, for, from, with, and about.

Prepositional phrases are phrases that begin with prepositions and include nouns, pronouns, and adjectives, e.g. on the shelf, by the author, with my father.

Both the SAT and ACT test a couple of errors involving prepositional phrases.

Most frequently, they test the “no comma before or after a preposition” rule — if you can recognize prepositions, this rule is extremely easy to apply. If you can’t, you have to puzzle things out by ear.

Prepositional phrases are also used to distract from subject-verb agreements, e.g. The forests of central Mexico provides an ideal habitat for Monarch butterflies.

In addition to knowing what prepositional phrases are, you must be able to recognize them so securely and consistently that you can remember, under pressure, to cross them out of potentially long and complicated sentences in order to check for disagreements.

2) Knowing the definitions of transition words

This is a big one. You probably don’t have any trouble with however and therefore, but what about less common transitions such as consequently, moreover, and nevertheless?

If you don’t know the literal meanings of these words as well as what sorts of relationships they’re used to indicate, you’ll have difficulty eliminating wrong answers and recognizing right ones. You might also start relying on how they sound (weird), and that’s usually a recipe for disaster.

3) Recognizing comma splices involving pronouns

A comma splice is formed when a comma rather than a period or semicolon is placed between two complete sentences. When this error involve two clearly separate sentences, it is generally easy to recognize; however, one very common problem arises when the second sentence begins with a pronoun (he, she, it, they, one) rather than a noun. Because the second sentence does not make sense out of context, many people falsely believe it cannot be a sentence.

Incorrect: The forests of central Mexico are warm and filled with a wide variety of plant life, they provide an ideal habitat for Monarch butterflies.

Correct: The forests of central Mexico are warm and filled with a wide variety of plant life. They provide an ideal habitat for Monarch butterflies.

Correct: The forests of central Mexico are warm and filled with a wide variety of plant life; they provide an ideal habitat for Monarch butterflies.

4) Being willing to read both forwards and backwards

One of the most important things to understand about SAT Writing/ACT English is that errors are context-based. As a result, the underlined portion of the sentence may not give you the information you need to answer a given question. Rather, the necessary information may be located elsewhere in the sentence or paragraph.

This skill is key for answering rhetoric questions that ask you to add, delete, or revise information. If you are asked about a topic sentence, for example, you must jump ahead and read the body of the paragraph in order to determine what topic the first sentence of the paragraph should introduce.

For example:

The exact elevation of Mt. Everest’s summit has long been a matter of controversy. In July, the warmest time of the year, temperatures average only about ?2°F on the summit; in January, the coldest month, summit temperatures average ?33 °F and can drop as low as ?76 °F. Storms can come up suddenly, and temperatures can plummet unexpectedly. The peak of Everest is so high that it reaches the lower limit of the jet stream, and it can be buffeted by sustained winds of more than 100 miles per hour. Precipitation falls as snow during the summer monsoon, and the risk of frostbite is extremely high.

Which of the following is the most effective introduction to the paragraph?

A. NO CHANGE

B. The climate of Mt. Everest is extremely hostile to climbers throughout the year.

C. Glacial action is the primary force behind the erosion of Mt. Everest and surrounding peaks.

D. The valleys below Everest are inhabited by Tibetan-speaking peoples.

In order to determine the answer, you must temporarily ignore the first sentence and instead focus on the rest of the paragraph — you cannot know what the topic sentence should be about until you know what sort of information it introduces. In this case, the paragraph discusses the extremely cold temperatures and dangerous weather conditions present on Mt. Everest. That corresponds to the phrase “hostile climate” in (B). Although the other answers refer to Mt. Everest, they are all off-topic.

5) Recognizing non-essential clauses

Simply put, a non-essential clause is a clause that can be eliminated from a sentence without affecting its essential structure or meaning. These clauses can be set off with either commas, dashes, or parentheses, but the same type of punctuation must be used at the beginning and end of the clause.

Correct: The peak known as El Capitan, which is considered by the majority of expert climbers to be the epicenter of the rock climbing world, is a vertical expanse stretching higher than the world’s tallest building, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai.

Correct: The peak known as El Capitan – which is considered by the majority of expert climbers to be the epicenter of the rock climbing world – is a vertical expanse stretching higher than the world’s tallest building, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai.

Correct: The peak known as El Capitan (which is considered by the majority of expert climbers to be the epicenter of the rock climbing world) is a vertical expanse stretching higher than the world’s tallest building, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai.

Incorrect answers to questions testing non-essential clauses often omit one or both of the punctuation marks surrounding the clause. They may also “mix and match” — for example, use a dash to end a non-essential clause begun by a comma, or vice versa.

To identify what type of punctuation should be used and where it should be placed, you must be able to identify where the non-essential clause logically begins and ends.

For example:

A mathematician, inventor, and philosopher, Charles Babbage, considered by some to be a “father of the computer” is credited with inventing the first mechanical computer.

A. NO CHANGE

B. computer is credited,

C. computer – is credited

D. computer, is credited

To answer this question, you must be able to recognize that the clause considered by some to be a “father of the computer” can be removed from the sentence without affecting its basic structure or meaning (A mathematician, inventor, and philosopher, Charles Babbage…is credited with inventing the first mechanical computer).

6) Distinguishing between number and tense

Number = singular or plural

Tense = past, present, or future

Consider the following sentence:

Incorrect: The relationship between goby fish and striped shrimp are truly symbiotic, for neither can exist without the other.

When asked to correct it, many students will simply change are to were. Not only does that not fix sentence, it misses the entire point of what’s being asked. And that becomes a problem when you encounter questions like this:

The relationship between sharks and remora fish are truly symbiotic, for neither can exist without the other.

A. are

B. is

C. have been

D. were

If you don’t clue into the fact that the verb must agree with the subject, the singular noun relationship, you have no real way of deciding between the answers.

Note that to answer subject-verb agreement questions, you also need to be able to distinguish between singular and plural verbs.

Singular verbs end in -s (e.g. he talks)

Plural verbs do not end in -s (e.g. they talk).

Many people associate -s with plural forms because, of course, plural nouns end in -s. Making the switch to verbs can be confusing, particularly when sentences are long and complicated, and subjects are separated from verbs. If you have a tendency to forget, write this rule down on the front of your test.

7) Recognizing formal vs. informal writing (register)

Questions testing diction, or word choice, appear frequently on both the SAT and the ACT. In some cases you must choose the word or phrase with the most appropriate meaning, while in others you must choose the word or phrase with the most appropriate tone or register — that is, the proper degree of formality or informality.

Passages are almost always written in a straightforward, moderately serious tone. Correct answers to register questions are consistent with the tone, whereas incorrect answers are typically too casual or slangy. They may also be excessively formal, but this is less common.

For example:

As a result of variations in snow height, light refraction, and gravity deviation, the exact elevation of Mt. Everest’s summit has long been a topic of debate. Beginning in the 1950s, numerous attempts were made to measure the summit’s true height.

A. NO CHANGE

B. a thing that people fight about.

C. a matter of great disputation.

D. the cause of a bunch of arguments.

In the above question, (B) and (D) are both awkward and overly casual, employing “vague,” highly informal words such as thing and bunch, whereas disputation in (C) is excessively formal. (A) is correct because it is consistent with the straightforward, middle-of-the-road tone found in the rest of the passage.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 29, 2015 | ACT English/SAT Writing, Grammar (SAT & ACT), SAT Grammar (Old Test), Uncategorized

Nouns

Nouns are the most common type of subjects. They include people, places, and things and can be concrete (book, chair, house) or abstract (belief, notion, theory).

Example: Bats are able to hang upside down for long periods because they possess specialized tendons in their feet.

Pronouns

Pronouns are words that replace nouns. Common pronouns include she, he, it, one, you, this, that, and there.

Less common pronouns include what, how, whether, and that, all of which are singular. They are typically used as part of a much longer complete subject (underlined in the second example below).

Example: They are able to hang upside down for long periods because they possess specialized tendons in their feet.

Example: How bats hang upside down for long periods was a mystery until it was discovered that they possess specialized tendons in their feet.

Gerunds

Gerunds are formed by adding -ING to the ends of verbs (e.g. read – reading; talk – talking). Although gerunds look like verbs, they act like nouns. They are always singular and take singular verbs.

Example: Hanging upside down for long periods is a skill that both bats and sloths possess.

Infinitives

The infinitive is the “to” form of a verb. Infinitives are always singular when they are used as subjects. They are most commonly used to create the parallel structure “To do x is to do y.”

Example: To hang upside down for a long period of time is to experience the world as a bat or sloth does.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 29, 2015 | Blog, College Admissions

From “Yale Students Campaign for All That Jazz:”

[Yale University Director of Bands Thomas C. Duffy] said he had encountered a shortage of qualified trombone and trumpet students, a situation he observed at other Ivy League schools trying to muster a big band. While he offered to lend music to the collective as it tried to reconstitute the jazz ensemble, he said he would be “stunned” if they could sustain 17 top-flight section players throughout the year.

Hmm… Tuba players have always been in short supply, but maybe the brass players will start getting ranked up there with the fencers and the squash players.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 28, 2015 | Blog, Issues in Education

But claiming that there is apparently makes for a good headline.

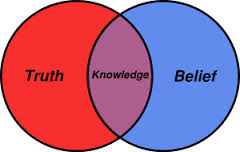

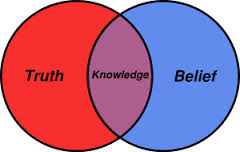

Knowledge and skills are intertwined; unless schools start acknowledging that critical thinking can only result from detailed content knowledge, conversations about what’s ailing American education will continue to be an exercise in nonsense.

The fact that anyone can use the phrase “knowledge-based learning” in a non-ironic way creeps me out to no end.

What’s next? Word-based reading? Number-based math? Language-based speech?

I don’t believe Common Core is really going to change many things here. It’s a set of skills; it does not lay out a coherent, specific body of knowledge. The ELA standards, at least, are so vague and repetitive as to be virtually meaningless, and would be met automatically in any rigorous traditional classroom headed by a knowledgeable, well-trained teacher.

If school districts use CC to implement a more content-rich curriculum, that is their choice. Requiring students to learn any particular set of facts, no matter how anodyne, is so politically contentious that no one would dare attempt such a thing at the national level.

Writing in the New York Times, Natalie Wexler acknowledges that:

…engineering the switch from skills to knowledge will take real effort. Schools will need to develop coherent curriculums and adopt different ways of training teachers and evaluating progress. Because the federal government can’t simply mandate a focus on knowledge, change will need to occur piecemeal, at the state, school district or individual school level.

To believe that such a change could miraculously occur “piecemeal” goes far beyond wishful thinking and into the realm of pure fantasy. And no, the fact that a bunch of people have downloaded a free online curriculum isn’t exactly going to compensate. Poor scores on CC tests are unlikely to simply “incentivize” low-income schools to shift over to a stronger emphasis on subject content, especially if their curriculums are effectively centered around test-prep. Besides, doing things in such a haphazard fashion is a pretty great way to ensure that huge disparities (geographic, economic, etc.) continue to exist.

When you take a crop of teachers indoctrinated by ed schools to believe that lecturing and memorization are forms of child abuse; pair them with administrators who use the threat of poor evaluations to keep less progressive teachers in line; and mix in an obsession with testing and accountability, you end up with a chaotic system driven by quick fixes. (But hey, no worries, the market will sort it out, right?)

In order for the focus to shift more towards teaching content, you need a critical mass of people who believe that subject knowledge is the basis for critical thinking, both in the classroom and in the administrative offices. Right now, those people are in pretty short supply. And with the number of people entering teaching dwindling, the chance of getting highly educated/knowledgeable/competent teachers, who believe even partially in the importance of transmitting knowledge, in front of classrooms on any sort of wide scale in the near future is pretty small.

The Right isn’t exactly helping here either. Rather than embrace what would actually be a conservative concept of education (classical curriculum, back-to-basics, etc.), they’re too busy screaming about school choice and privatizing everything.

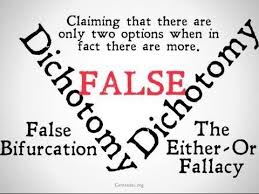

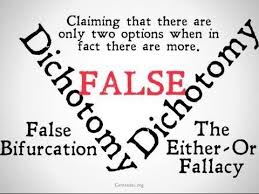

It’s a perfect storm of factors, and while everyone is busy setting up false dichotomies and waiting for technology to save the day, the descent into chaos continues.

I think a commenter named Emile from NY said it best:

I don’t know in depth the various pedagogical theories about K-12 education, but from the perspective of a college professor who’s been teaching at a mid-tier university for more than 25 years, K-12 education has been in a steady decline over the past few decades, and [E.D.] Hirsch is absolutely right about the reason for it.

I ask everyone in K-12 education this: What should a college professor who is teaching a course on Enlightenment ideas do in the face of a whole class of intelligent freshmen who don’t know the dates of the Civil War, or the Second World War, or the French Revolution, or know that once upon a time there was a Roman Empire? How, exactly, would you proceed? Or how, exactly, would you proceed in a basic college course in mathematics when faced with a college class of intelligent freshmen that can’t, as a whole, move easily between fractions, decimals and percents?

People hate the word “memorization,” but I’m here to tell you students love it. People who malign memorization often ask, “Why should anyone memorize dates that they’re bound to forget?” Not every date is remembered over the long haul, but the mind loves inductive reasoning, and has a way of gathering particular dates loosely into centuries, and from there building a kind of organized closet into which more knowledge can be added.

I’m not suggesting that first graders need to be able to able to discourse in detail about ancient Mesopotamia, but seriously, is it that unreasonable for college students to be expected to have a basic understanding of what happened in the past?

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 23, 2015 | ACT English/SAT Writing, Blog, SAT Grammar (Old Test)

Shortcut: semicolon + and/but = wrong

If you see an answer choice on either the SAT or the ACT that places a semicolon before the word and or but, cross out that answer immediately and move on.

Why? Because a semicolon is grammatically identical to a period, and you shouldn’t start a sentence with and or but.

The slightly longer explanation: In real life, semicolon usage is a little more flexible, and the choice to use when can sometimes be more a matter of clarity/style than one of grammar. It is generally considered acceptable to place a semicolon before and or but in order to break up a very long sentence, especially when there are already multiple commas/clauses.

For example:

Pamela Meyer, a certified fraud examiner, author, and entrepreneur, became interested in the science of deception at business school workshop during which a professor detailed his findings on behaviors associated with lying; and she subsequently worked with a team of researchers to survey and analyze existing research on deception from academics, experts, law enforcement, the military, espionage and psychology.

In the above sentence, either a comma or a semicolon could be used before and. In this case, however, the sentence is so long and contains so many different parts that the semicolon is a logical choice to create stronger break between the parts.

Why not just use a period? Well, because a semicolon implies a stronger connection between the clauses than a period would; it keeps the sentence going rather than marking a full break between thoughts. Again, this is a matter of style, not grammar.

The SAT and the ACT, however, are not interested in these details. Rather, their goal is to check whether you understand the most common version of the rule. Anything beyond that would simply be too ambiguous.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 20, 2015 | Blog, General Tips, The New SAT, Tutoring

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere on this site, I’m often a tutor of last resort. That is, people find their way to me after they’ve exhausted other test-prep options (self-study, online program, private tutor) and still find themselves short of their goals. Sometimes very, very far short of their goals. When people come to me very late in the process, e.g. late spring of junior year or the summer before senior year, there’s unfortunately a limited amount that I can do. Most of it is triage at that point: finding and focusing on a handful of areas in which improvement is most likely.

Not coincidentally, many of the students in this situation who find their way to me have been cracking their heads against the SAT for months, sometimes even a year or more. Often, they’re strong math and science students whose reading and writing scores lag significantly behind their math scores, even after very substantial amounts of prep and multiple tests. They’re motivated, diligent workers, but the verbal is absolutely killing them. Basically, they’re fabulous candidates for the ACT. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 19, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT

In case you haven’t seen them, they can be downloaded https://collegereadiness.collegeboard.org/sat/practice/full-length-practice-tests

The basic formula for determining scaled scores is simple enough (count how many you got right, convert to a raw score, and multiple by 10); however, if I hadn’t witnessed some of the College Board’s recent antics, I sincerely would have thought that the subscore charts were some kind of parody.

If want a definition for convoluted (assuming you’re taking the SAT before March 2016), this pretty much sums it up. Just looking at those charts gives me a headache.

I’m sorry, but does anyone truly think that college admissions officers with thousands of applications to get through are going to even LOOK at those sub-scores?

But as everyone knows, more data is always better. Except, of course, when it isn’t.