by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 6, 2015 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

I’m not sure how I missed it when it came out, but Barry Garelick and Katherine Beals’s “Explaining Your Math: Unnecessary at Best, Encumbering at Worst,” which appeared in The Atlantic last month, is a must-read for anyone who wants to understand just how problematic some of Common Core’s assumptions about learning are, particularly as they pertain to requiring young children to explain their reasoning in writing.

(Side note: I’m not sure what’s up with the Atlantic, but they’ve at least partially redeemed themselves for the very, very factually questionable piece they recently ran about the redesigned SAT. Maybe the editors have realized how much everyone hates Common Core by this point and thought it would be in their best interest to jump on the bandwagon, but don’t think that the general public has yet drawn the connection between CC and the Coleman-run College Board?)

I’ve read some of Barry’s critiques of Common Core before, and his explanations of “rote understanding” in part provided the framework that helped me understand just what “supporting evidence” questions on the reading section of the new SAT are really about.

Barry and Katherine’s article is worth reading in its entirety, but one point that struck me as particularly salient.

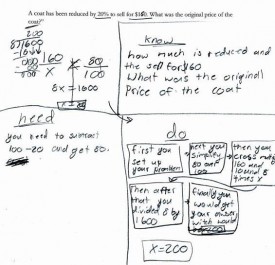

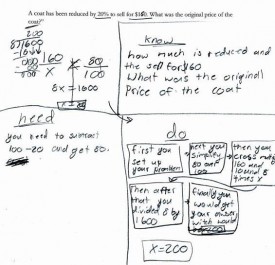

Math learning is a progression from concrete to abstract…Once a particular word problem has been translated into a mathematical representation, the entirety of its mathematically relevant content is condensed onto abstract symbols, freeing working memory and unleashing the power of pure mathematics. That is, information and procedures that have been become automatic frees up working memory. With working memory less burdened, the student can focus on solving the problem at hand. Thus, requiring explanations beyond the mathematics itself distracts and diverts students away from the convenience and power of abstraction. Mandatory demonstrations of “mathematical understanding,” in other words, can impede the “doing” of actual mathematics.

Although it’s not an exact analogy, many of these points have verbal counterparts. Reading is also a progression from concrete to abstract: first, students learn that letters are represented as abstract symbols, and that those symbols correspond to specific sounds, which get combined in various ways. When students have mastered the symbol/sound relationship (decoding) and encoded them in their brains, their working memories are freed up to focus on the content of what they are reading, a switch that normally occurs around third or fourth grade.

Amazingly, Common Core does not prescribe that students compose paragraphs (or flow charts) demonstrating, for example, that they understand why c-a-t spells cat. (Actually, anyone, if you have heard of such an exercise, please let me know. I just made that up, but given some of the stories I’ve heard about what goes on in classrooms these days, I wouldn’t be surprised if someone, somewhere were actually doing that.)

What CC does, however, is a slightly higher level equivalent — namely, requiring the continual citing of textual “evidence.” As I outlined in my last couple of posts, CC, and thus the new SAT, often employs a very particular definition of “evidence.” Rather than use quotations, etc. to support their own ideas about a work or the arguments it contains (arguments that would necessarily reveal background knowledge and comprehension, or lack thereof), students are required to demonstrate their comprehension over and over again by “staying within the four corners of the text,” repeatedly returning it to cite key words and phrases that reveal its meaning — in other words, their understanding of the (presumably) self-evident principle that a text means what it means because it says what it says. As is true for math, entire approach to reading confuses demonstration of a skill with “deep” possession of that skill.

That, of course, has absolutely nothing to do with how reading works in the real world. Nobody, nobody, reads this way. Strong readers do not need to stop repeatedly in order to demonstrate that they understand what they’re reading. They do not need to point to words or phrases and announce that they mean what they mean because they mean it. Rather, they indicate their comprehension by discussing (or writing about) the content of the text, by engaging with its ideas, by questioning them, by showing how they draw on or influence the ideas of others, by pointing out subtleties other readers might miss… the list goes on and on.

Incidentally, I’ve had adults gush to me that their children/students are suddenly acquiring all sorts of higher level skills, like citing texts and using evidence, but I wonder whether they’re actually being taken in by appearances. As I mentioned in my last post, although it may seem that children being taught this way are performing a sophisticated skill (“rote understanding”), they are actually performing a very basic one. I think Barry puts it perfectly when he says that It is as if the purveyors of these practices are saying: “If we can just get them to do things that look like what we imagine a mathematician does, then they will be real mathematicians.”

In that context, these parents’/teachers’ reactions are entirely understandable: the logic of what is actually going on is so bizarre and runs so completely counter to a commonsense understanding of how the world works that such an explanation would occur to virtually no one who hadn’t spent considerable time mucking around in the CC dirt.

To get back to the my original point, though, the obsessive focus on the text itself, while certainly appropriate in some situations, ultimately serves to prohibit students from moving beyond the text, from engaging with its ideas in any substantive way. But then, I suspect that this limited, artificial type of analysis is actually the goal.

I think that what it ultimately comes down to is assessment — or rather the potential for electronic assessment. Students’ own arguments are messier, less “objective,” and more complicated, and thus more expensive, to assess. Holistic, open-ended assessment just isn’t scalable the same way that computerized multiple choice tests are, and choosing/highlighting specific lines of a text is an act that lends itself well to (cheap, automated) electronic grading. And without these convenient types of assessments, how could the education market ever truly be brought to scale?

by Erica L. Meltzer | Nov 29, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT

In my previous post, I examined the ways in which most so-called “supporting evidence” questions on the new SAT are not really about “evidence” at all, but are actually literal comprehension questions in disguise.

So to pick up where I left off, why exactly is the College Board reworking what are primarily literal comprehension questions in such an unnecessarily complicated way?

I think there are a couple of (interrelated) reasons.

One is to create an easily quantifiable way of tracking a particular “critical thinking” skill. According to the big data model of the world, things that cannot be tagged, and thus analyzed quantitatively, do not exist. (I’m tagged, therefore I am.) According to this view, the type of open-ended analytical essays that actually require students to formulate their own theses and analyze source material are less indicative of the ability to use evidence than are multiple-choice tests. Anything holistic is suspect.

The second reason – the one I want to focus on here – is to give the illusion of sophistication and “rigor.”

Let’s start with the fact that the new SAT is essentially a Common Core capstone test, and that high school ELA Common Core Standards consist pretty much exclusively of formal skills, e.g. identifying main ideas, summarizing, comparing and contrasting; specific content knowledge is virtually absent. As Bob Shepherd puts it, “Imagine a test of biology that left out almost all world knowledge about biology and covered only biology “skills” like—I don’t know—slide-staining ability.”

At the same time, though, one of the main selling points of Common Core has been that it promotes “critical thinking” skills and leads to the development of “higher-order thinking skills.”

The problem is that genuine “higher order thinking” requires actual knowledge of a subject; it’s not something that can be done in a box. But even the new SAT is being touted as a “curriculum-based test,” it can’t explicitly require any sort of pre-existing factual knowledge – at least not on the verbal side. Indeed, the College Board is very clear about insisting that no particular knowledge of (mere rote) facts is needed to do well on the test. So there we have a paradox.

To give the impression of increased rigor, then, the only solution was to create an exam that tested simple skills in inordinately convoluted ways – ways that are largely detached from how people actually read and write, and that completely miss the point of how those skills are applied in the real world.

That is, not coincidentally, exactly the same criticism that is consistently directed at Common Core as a whole, as well as all the tests associated with it (remember comedian Louis C.K.’s rant about trying to help his daughter with her homework?)

In practice, “using evidence” is not an abstract formal skill but a context-dependent one that arises out specific knowledge of a subject. What the new SAT is testing is something subtly but significantly different: whether a given piece of information is consistent with, a given claim.

But, you say, isn’t that the very definition of evidence? Well…sort of. But in the real world (or at least that branch of it not dominated by people completely uninterested in factual truth), “using evidence” isn’t simply a matter of identifying what texts say, i.e. comprehension, but rather using information, often from a variety of sources, to support an original argument. That information must not only be consistent with the claim it is used to support, but it must also be accurate.

To use evidence effectively, it is necessary to know what sources to consult and how to locate them; to be aware of the context in which those sources were produced; and to be capable of judging that validity of the information they present — all things that require a significant amount of factual knowledge.

Evidence that is consistent with a claim can also be suspect in any number of ways. It can be partially true, it can be distorted, it can be underreported, it can be exaggerated, it can be outright falsified… and so on. But there is absolutely no way to determine any of these things in the absence of contextual/background knowledge of the subject at hand.

Crucially, there is also no way to leap from practicing the formal skill of “using evidence,” as the College Board defines it, to using evidence in the real world, or at least in the way that college professors and employers will expect students/employees to use it. If you don’t know a lot about a subject, your ability to analyze – or even to fully comprehend – arguments concerning it will be limited, regardless of how much time you have spent labeling main ideas and supporting details. That is why even the most motivated students can hit the 700 wall in SAT Critical Reading, sometimes while scoring 800s in Math and Writing; there are a sufficient number of holes in their general knowledge that there’s always something they misunderstand. There is no short-term way to get around that weakness, no matter how many “main point” or “primary purpose” questions they do.

This (misc)conception of “evidence” as a strictly formal skill leads to a parody of what real-world academic inquiry actually consists of. A 16 year-old might impress her teacher by throwing around words like “discourse,” but that does not mean that her analytical abilities are in any way comparable to those of a 50-year old tenured historian with a Ph.D., a list of peer-reviewed articles, and a couple of books under her belt — not to mention a rock-solid understanding of the chronology, major players, and running debates in her particular area of specialization, as well as the ability to sit still, take notes, and listen to her colleagues speak for long stretches at a time. Yet the College Board is effectively insisting that by superficially mimicking certain aspects of the work that actual scholars do, teenagers can leapfrog over years of hard work and magically acquire adult skills. (Ever watched a high school sophomore try to complete an exercise in “historical thinking” about the Spanish conquest of the New World when she isn’t quite sure who the Amerindians were? I have, and it’s not pretty.)

In his “Common-Sense Approach to Common Core Math” series, Barry Garelick makes this point as well:

[Students] are taught to reproduce explanations that make it appear they possess understanding—and more importantly, to make such demonstrations on the standardized tests that require them to do so. And while “drill and kill” has been held in disdain by math reforms, students are essentially “drilling understanding.”

The repeated going back to the text to answer “evidence” questions serves exactly the same purpose; it gives the appearance that students are performing a sophisticated skill when in fact they’re doing nothing of the sort. The underlying issue, namely that students might not actually understand what they read because of deficiencies in vocabulary and background knowledge, is conveniently sidestepped.

I suspect that the College Board’s “skills and knowledge” slogan was created in an attempt to head off this criticism. By cannily associating (eliding) those two things, the College Board implies that it knows just what this whole education thing is really about, and that the new SAT reflects…well, all that good stuff.

Let us recall, though, that Common Core standards essentially had to consist of a series of empty formal skills slapped together and pushed through as quickly as possible in order to circumvent close investigation or pushback. Factual knowledge was an afterthought. It was never dealt with because it was politically inconvenient and could easily have led to the sort of controversy that would have deterred governors from signing on to the standards.

As a result, proponents of Common Core are left to assert that the knowledge element will somehow just take care of itself. Exactly how that is supposed to happen is never explained, but rest assured, it just will. That is how you get nonsensical articles like Natalie Wexler’s New York Times piece, “How Common Core Can Help in the Battle of Skills vs. Knowledge”. As it turns out, Wexler chairs the board of trustees at an organization called Writing Revolution… an organization that David Coleman just happens to sit on the board of. That’s quite a coincidence, is it not?

by Erica L. Meltzer | Nov 26, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT

As I’ve written about recently, the College Board (and David Coleman in particular) appears to have a somewhat tenuous relationship to the concept of evidence. It is therefore entirely unsurprising that the new SAT reflects this muddled definition.

Consider the following:

In a normal academic context, the word “evidence” refers to information (facts, statistics, anecdotes etc.) used to support an argument.

An argument is, by definition, a debatable statement. The point of using evidence is to provide support for one side or the other. On the other hand, reality-based statements that cannot be argued with, at least under normal circumstances, are generally considered facts. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Nov 18, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT

A couple of days ago, I was interviewed by Michael Arlen Davis for his forthcoming documentary The Test (working title).

Michael had interviewed me before, but this time he wanted to talk about the recent series of blog posts in which I’ve taken the College Board to task for the many inconsistencies and, shall we say, questionable claims regarding the new SAT.

One of the things that Michael asked me in the course of the interview was why so few people seemed to be talking about these issues and why, when they were brought up, they were usually dealt with in such as cursory and superficial manner.

As I explained, I’m a little taken aback that so few people are (publicly) scratching below the surface of the College Board’s claims in anything resembling a substantive manner. After all, only a very small amount of scrutiny is necessary to poke holes in many of those claims. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Nov 15, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT, Vocabulary

I’ve been following Diane Ravitch’s blog for a while now. I think she does a truly invaluable job of bringing to light the machinations of the privatization/charter movement and the assault on public education. (I confess that I’m also in awe of the sheer amount of blogging she does — somehow she manages to get up at least three or four posts a day, whereas I count myself lucky if I can get up that every couple of weeks.)

I don’t agree with her about everything, but I was very much struck by this post, entitled “The Reformers’ War on Language and Democracy.”

Diane writes:

Maybe it is just me, but I find myself outraged by the “reformers'” incessant manipulation of language. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Nov 8, 2015 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

I’ve been doing some more pondering about the claims of increased equity attached to the new SAT, and although I’m still trying to sift through everything, I’ve at least managed to put my finger on something that’s been nagging at me.

Basically, the College Board is now espousing two contradictory views: on one hand, it trumpets things like the inclusion of “founding documents” in order to proclaim that the SAT will be “more aligned with what students are doing in school,” and on the other hand, it insists that no particular outside knowledge is necessary to do well on the reading portion of the exam.

While that assertion may contain a grain of truth – some very strong readers with just enough background knowledge will be able to able to navigate the test without excessive difficulty – it is also profoundly disingenuous. Comprehension can never be completely divorced from knowledge, and even middling readers students who have been fed a steady diet of “founding documents” in their APUSH classes will be at a significant advantage over even strong readers with no prior knowledge of those passages.

You really can’t have it both ways. If background knowledge truly isn’t important and the SAT is designed to be as close to a pure reading test as possible, then every effort should be made to use passages that the vast majority of students are unlikely to have already seen. (That perspective, incidentally, is the basis for the current SAT.)

On the flip side, a test that is truly intended to be aligned with schoolwork can only be fair if everyone taking the test is doing the same schoolwork – a virtual impossibility in the United States. That’s not a bug in the system, so to speak; it is the system. Even if Common Core had been welcomed with open arms, there would still be a staggering amount of variation.

To state what should be obvious, it is impossible to design an exam that is aligned with “what students are learning in school” when even students in neighboring towns – or even at two different schools in the same town – are doing completely different things. Does anyone sincerely think that students in public school in the South Bronx are doing the same thing as those at Exeter? Or, for that matter, that students in virtual charter schools in Mississippi are doing the same things as those in public school in Scarsdale? Yet all of these students will be taking the exact same test.

The original creators of the SAT were perfectly aware of how dramatically unequal American education was; they knew that poorer students would, on the whole, score below their better-off peers. Their primary goal was to identify the relatively small number of students from modest backgrounds who were capable of performing at a level comparable to students at top prep schools. Knowing that the former had not been exposed to the same quality of curriculum as the latter, they deliberately designed a test that was as independent as possible from any particular curriculum.

So when people complain that the SAT doesn’t reflect, or has somehow gotten away from, “what students are doing in school,” they are, in some cases very deliberately, missing the whole point – the test was never intended to be aligned with school in the first place. Given the American attachment to local control of education, that was not an irrational decision. (Although I somehow doubt they could have ever imagined the industry, not to mention the accompanying stress, that would eventually grow up around the exam.)

Viewed in this light, the attempt to create a school-aligned SAT can actually be seen as a step backwards – one that either dramatically overestimates the power of Common Core to standardize curricula, or that simply turns a blind eye to very substantial differences in the type of work that students are actually doing in school.

The problem is even more striking on the math side than on the verbal. As Jason Zimba, who led the Common Core math group, admitted, Common Core math is not intended to go beyond Algebra II, yet the SAT math section will now include questions dealing with trigonometry – a subject to which many juniors will not yet have been exposed. (For more about the problems with math on the new exam, see “The Revenge of K-12: How Common Core and the New SAT Lower College Standards in the U.S.” as well as “Testing Kids on Content They’ve Never Learned” by blogger Jonathan Pelto.) In that regard, the new SAT is even more misaligned with schoolwork than the reading. The current exam, in contrast, does not go beyond Algebra II – the focus is on material that pretty much everyone taking a standard college-prep program has covered.

The unfortunate reality is that disparities in test scores reflect larger educational disparities; it’s a lot easier to blame a test than to address underlying issues, for example the relationship between tax dollars and public school funding. Yes, the test plays a role in the larger system of inequality, but it is one factor, not the primary cause. Any nationally-administered exam, whatever it happens to be called, will to some extent reflect the gap (unless, of course, you start with the explicit goal of engineering a test on which everyone can do well and work backwards to create an exam that ensures that outcome).

Assuming, however, that the goal is not to design an exam that everyone aces, then there’s no obvious way out of the impasse. Create an exam that isn’t tied to any particular curriculum, and students are forced to take time away from school to prepare. Create an exam that’s “curriculum-based,” and you inevitably leave out huge numbers of students since there’s no such thing as a standard curriculum.

Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Nov 4, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT

This is another little oddity I came across on the College Board website. While poking around, trying to find information about the connection between the College Board and The Atlantic in an attempt to explain why the latter was publishing false information about the SAT, I ended up on the AP US History (APUSH) professional development page – specifically the section devoted to teaching using historical documents to teach “close reading” and analytical writing.

I’d heard about the controversy surrounding the redesigned AP test, and I was curious just what the College Board was preaching to teachers in terms of how to prepare students for the new exam. Although I probably shouldn’t be surprised by these things anymore, I was a bit taken aback by the multiple-choice “check for understanding” questions. The page is, after all, designed for adult professionals, a reasonable number of whom hold graduate degrees; for those of you who don’t care to read, let’s just say it’s not exactly what anyone would call a sophisticated pedagogical approach.

What really shocked me, however, was this video of a model AP classroom, in which a group of students discuss a primary source document about… you guessed it, Frederick Douglass and the 4th of July. Based on everything I’ve heard about the PSAT, this was almost certainly the same passage that appeared on that test.

While the video must have made a while ago to coincide with the first administration of the new APUSH exam — the students featured in it are presumably well past the point of taking the PSAT — there’s still something not quite kosher about the College Board swearing students to secrecy about the content of an exam when content from that exam was presented on its website (albeit in a section students are exceedingly unlikely to find on their own) before the exam was even administered.

It also got me wondering whether passages (“founding documents” or otherwise) that will appear on the new SAT are already presented or alluded to elsewhere on the College Board’s website. In particular, at the possibility that the “founding documents” that appear on the SAT will simply be chosen from among the key APUSH primary source documents. Assuming that the Official Guide is accurate, there will be non-American documents as well, but it seems like a reasonable assumption that many of the documents will issue from that list.

Again, something seems a little off here. This is a list intended for APUSH classes; surely there are many US history classes across the country that will not have such a heavy focus on primary-source documents. If the students who read these documents in school prior to encountering them on the SAT are primarily APUSH students, where does that leave everyone else? Even a strong reader is at a disadvantage if he or she has limited knowledge of a topic, and most students are not exactly racing home after school and reading Frederick Douglass for fun.

You cannot create an internationally administered exam that is given to students following every sort of curriculum imaginable and then claim is is somehow aligned with “what students are doing in school.” Rather, it is aligned — or intended to be aligned — with what some students doing in school. Exactly how is that supposed to make things more equitable?

by Erica L. Meltzer | Nov 3, 2015 | Blog, SAT Critical Reading (Old Test)

After I posted a support/undermine question as my question of the day last week, I got a message from a student asking me if I could put up more reading questions that require more extended reasoning (usually corresponding to Level 4 and 5 Critical Reading questions on the pre-March 2016 SAT). As I explained to the student, these questions are unfortunately extremely time-consuming to produce; I sometimes need to tinker with them for a few days to get them into shape.

Given that, I started thinking about what students could do in order to get more practice on these question types, which normally show up no more than once or twice per test. Even if someone uses both the Blue Book and the College Board online program, there still aren’t a whole lot of them. The problem, of course, is that these are the exact questions that a lot of people stuck in the high 600s/low 700s need to focus on.

It finally occurred to me that the reading portions of the GRE (Master’s and Ph.D. admissions), GMAT (MBA admissions), and LSAT (law school admissions) are chock full of these types of questions.

The GRE in particular is a great source of practice material because it’s written by ETS; the “flavor” and style of the tests are the same. And you can sit and do support/undermine questions to your heart’s content.

Now, to be clear: this is not a recommendation I would make to anyone not aiming for an 800, or at least a 750+. These tests are considerably harder than the SAT; if you’re not comfortable reading at a college level, trying to work with prep material geared toward graduate-level exams is likely to be an exercise in frustration. Unlike SAT passages, which are taken from mainstream “serious” non-fiction, graduate exam passages tend to be taken from academic articles — the work is written for subject specialists, not a general audience.

I would also not recommend this option unless you’ve already exhausted all the authentic SAT practice material at your disposal.

But if you do happen to fall into that category and are chomping at the bit for more material, you might want to consider the official guides for these tests as supplemental options. If you spend some time working with them, you’ll probably be surprised at how easy the SAT ends up seeming by comparison.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Nov 2, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT

Dear College Board:

I understand that you are very busy helping students prepare for college and career readiness success in the 21st century; however, as I was perusing (excuse me, looking at) the section of your website devoted to describing the essay contest run jointly by your organization and The Atlantic magazine, I couldn’t help but notice a sentence that read as follows:

“To be successful at analytical writing, students must support your arguments with evidence found in the text and clearly convey information to the reader.”

As the writers of your website copy presumably know, the correct use of parallel structure and pronoun agreement is an important component of analytical writing — the exact type of writing that employees use authentically in their actual careers.

Moreover, given that your organization is responsible for testing over 1.5 million students on these exact concepts annually, I assume that the appearance of this type of faulty construction is simply the result of an oversight rather than any sort of indication that College Board writers lack the skills and knowledge necessary for success in the 21st century — that is, the skills and knowledge that matter most.

As you update your website to reflect the upcoming changes to the SAT, however, do try to remember that carefully editing your work is also an important skill for college and career readiness. After all, you wouldn’t want to set a poor example.

Best,

Erica

by Erica L. Meltzer | Nov 1, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT

Ever since I encountered Emmanuel Felton’s article “How the Common Core is Transforming the SAT” a couple of days ago and wrote my ensuing diatribe, I’ve been trying to figure out just why The Atlantic in particular would publish information so blatantly false. Sure, there have been plenty of articles regurgitating the standard hype about the new test, in pretty much every major media outlet, but this one crossed a line.

To be perfectly fair, Felton doesn’t actually state flat-out that analogies are still included on the test, but with lines such as On the reading side, gone are analogies like “equanimity is to harried” as “moderation is to dissolute,” the implication is so strong that it’s pretty much impossible for casual readers not to draw that conclusion.

Then, halfway through my run this morning, I had a “duh” moment. I had somehow forgotten that the Atlantic had partnered with the College Board to run an annual “analytical writing” contest for high school students.

In fact, James Bennett, the president and editor-chief of The Atlantic even appears in this College Board video on analytical writing for the new APUSH exam. That exam is Coleman’s baby.

Coincidence? I think not.

Mystery solved.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 31, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT, Uncategorized

From Emmanuel Felton’s Atlantic article, “How the New SAT is Taking Cues from Common Core:

While other standardized tests have also been criticized for rewarding the students who’ve mastered the idiosyncrasies of the test over those who have the best command of the underlying substance, the SAT—with its arcane analogy questions and somewhat counterintuitive scoring practices—often received special scorn.

And this:

On the reading side, gone are analogies like “equanimity is to harried” as “moderation is to dissolute…Eliminating “SAT words” isn’t the only change to the new reading and writing section, which will require a lot more reading…The passages themselves are changing, as The College Board tries to have them represent a range of topics from across the disciplines of social studies, science, and history.

Emmanuel Felton is entitled to his own opinion about the SAT; he is not entitled to his own facts.

The SAT eliminated analogy questions in 2005 — that was 10 full years ago, in case you didn’t care to do the math. Yet his article very directly implies that these questions are still part of the exam.

Felton also does not acknowledge that the SAT already includes passages drawn from fiction, social science, science, and history, on every single test. The fact that the passages are not explicitly labeled as such, as they are on the ACT, does not mean that they are drawn randomly.

These are exceedingly basic facts, which presumably could have been checked with five seconds of internet research and a quick glance through the Official Guide.

Does the Atlantic not employ fact-checkers? Or does it simply not care about facts?

Furthermore, the small print at the bottom of Felton’s article indicates that it was written “in collaboration with the Hechinger Report.” On its website, The Hechinger Report describes itself as “… an independent nonprofit, nonpartisan organization based at Teachers College, Columbia University. We on support from foundations and individual donors to carry out our work.” (Unsurprisingly, the Gates Foundation is listed among those donors.)

Why on earth is a publication produced by an Ivy League university allowing this type of blatant misinformation to be disseminated?

If you are going to take potshots at the SAT in a major national magazine, fine; people have been doing that for decades. At the very least, though, those criticisms should be anchored in some sort of reality.

Even by the very questionable standards of general reporting about the new SAT, this is sloppy, lazy work.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 31, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT

A month or so ago, when I first became aware of the questions surrounding ETS’s involvement (or lack thereof) in the new SAT, I wrote to several people who had been vocal about criticizing Common Core and the slapdash manner in which it was thrown together by Coleman et. al. One of the people I contacted was Jim Milgram, whose response I cited in an earlier post; the other was his colleague Sandra Stotsky, the other member of the validation committee who refused to sign off on the Standards.

Unfortunately, neither of them was able to offer any insight into the authorship of the SAT; however, Sandra did suggest that I write to Valerie Strauss at the Washington Post and alert her to the College Board’s deliberate and persistent evasiveness regarding that question. (The Post’s Education section, unlike that of the Los Angeles Times, hasn’t been bought out by one of the billionaires funding the reform movement… at least not yet.) Valerie promptly responded to let me know that she found the issue “fascinating” and would do some investigation of her own.

So stay tuned. If enough people start asking questions, perhaps the powers that be at the College Board will finally be forced into providing some answers — no doubt heaping on scads of reformster gibberish in an attempt evade the issue at every step. (Transparency? What transparency?). But at least that would be a step in the right direction.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 29, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT

After listening to me natter on about who was writing the new SAT, a tutor friend of mine decided to take matters into her own hands and email the College Board.

Just as I had predicted, the response (posted below) consisted of a non-answer packed full of every favorite reformer platitude imaginable (College and career readiness! measuring skills and knowledge! evidence for validity! Ummm… It hasn’t been administered yet. Exactly how does one go about acquiring evidence for the validity of something before it’s occurred?).

This was my friend’s original inquiry:

Hi,

I’m just wondering if the new redesigned SAT and PSAT were written/designed by ETS.

Thanks!

And this is the response she received from the College Board:

Subject

Inquiry for SAT

Discussion Thread

Response Via Email (Vivian Agent ID 192285) 10/22/2015 02:27 PM

Thank you for contacting the College Board.

We have received your email in reference to the redesigned SAT and PSAT exams. We will be more than happy to assist you and provide you with some information.

To establish a strong foundation of evidence for validity, the new test design is based on a growing body of national and international research on the skills and knowledge needed for college and career readiness and success. Great care goes into developing and evaluating every question that appears on the SAT and PSAT exams. College Board test development committees, made up of experienced educators and subject-matter experts, advice on the test specifications and the types of questions that are asked. Before appearing in a test form that will count toward a student’s score, every potential SAT and PSAT question is:

• Reviewed by external subject-matter experts, such as math or English educators, to make sure it reflects the knowledge and skills that are part of a rigorous high school curriculum.

• Subjected to an independent fairness review process.

• Pretested on a diverse sample of students under live testing conditions for analysis by subgroups.

Meticulous care goes into developing and evaluating each test for fairness. Classroom teachers, higher education faculty who teach freshman courses, test developers, and other trained content experts write the test questions for the SAT and PSAT exams. Test developers, trained content experts, and members of subject-based development committees write the test questions for the SAT Subject Tests.

Test development committees, made up of racially/ ethnically diverse high school and college educators from across the country, review each test item and test form before it is administered. To ensure that the SAT, SAT Subject Tests, and PSAT are valid measures of the skills and knowledge specified for the tests, as well as fair to all students, the SAT Program maintains rigorous standards for administering and scoring the tests.

Careful and thorough procedures are involved in creating the test. Educators monitor the test development practices and policies and scrupulously review each new question to ensure its utility and fairness. Each test question is pretested before use in an actual SAT, SAT Subject Test, and PSAT exams. Not until this rigorous process is completed are newly developed questions finally used in the administrations.

For further information or assistance, please feel free to call us at 1 (866) 756-7346 (Domestic), 001 (212) 713-7789 (International), Monday through Friday, from 8:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. (Eastern Time) or visit us at www.collegeboard.org.

Thank You,

Vivian

Agent ID #192285

The College Board Service Center

The only part that took me even slightly aback was the length; I guess it’s hard to say nothing concisely. At any rate, it’s a masterpiece of obfuscation — “obfuscation” being highly relevant word that means “deliberating making something unclear in order to avoid awkward or unpleasant facts.”

So while it’s reassuring to know that the writing committees are made up of “racially and ethnically diverse high school and college educators” (does that include current classroom teachers or just administrators?), it would also be nice to have a straight answer regarding whether ETS is still involved, and if so, in what capacity?

As Larry Krieger put it:

Why not just be succinct and say: “Yes, the ETS is responsible for the new SATs.” Or, “No a new team at Pierson [sic] is responsible for the new SATs.”

Reading between the lines, I would assume the answer is no but that the College Board has imposed some sort of prohibition against admitting as much directly — presumably because they don’t want to stir things up, and because that type of admission could lead to awkward questions about things like validity. Proclaiming that the new test is “relevant” has gotten the College Board pretty far, but then again the same thing happened with Common Core before people actually understood anything about it. The other tests linked to Common Core have already come under plenty of fire; the last thing the College Board needs is to be linked to that kind of controversy.

It could just be me, but something doesn’t seem right here.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 28, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT

A while back, in the course of my discussion about how to choose between the current SAT, the new SAT, and the ACT, I mentioned in passing that the SAT would no longer be written by ETS. Larry Kreiger (of Direct Hits and APUSH Crash Course fame) posted a comment expressing his surprise and asking what my source was for that information.

I responded somewhat sheepishly to Larry that I didn’t actually remember — I had been given the information so long ago that I actually no longer recalled who had told it to me. Until Larry asked me, I had just assumed it was common knowledge, or at least somewhat common knowledge.

As I pointed out in my previous post, the tests released thus far seem sloppier and less consistent than what I’ve come to expect from ETS (more about that another time). Even when correct answers were justified, they seemed to be lacking the precision I’ve come to associate with the SAT. Granted, that could be because the details of the test are still being worked out, but these questions simply didn’t have an ETS feel. Having spent countless hours analyzing SAT questions in order to mimic them as effectively as possible, I think my instincts are pretty reliable.

Larry’s response to me, however, was as follows:

I can tell you that the CB has a long standing contract with the ETS. In fact they have a person who earns a six figure salary whose job is to monitor the contract. Given the lack of an authoritative source I believe it is likely that the ETS is writing the new test. I do agree that the questions are below the usual ETS standards.

I was willing concede that I – or, rather, my source – had been mistaken, but now my curiosity was piqued. I didn’t want to be responsible for disseminating misinformation, but something about those questions seemed “off.”

I did some googling, which turned up absolutely nothing.

I also tried calling the College Board where, after a several surprised silences, various representatives quickly passed me off to other representatives, who eventually left me right back at the original menu. I considered making some further attempts; however, after considering that any response I did manage to elicit would inevitably consist of a non-answer involving edu-babble about “best practices,” “evidence-based standards,” “21st century skills,” and “preparation for college and career readiness,” I decided I was better off pursuing other avenues.

I got back in touch with the blog-reader who had worked for ETS several decades ago and had written to me to express her surprise at the clearly lowered standards. She mentioned that she’d heard David Coleman had “cleaned house” and had fired many experienced ETS writers, and that some of the sloppiness could be attributed to that.

When I thought about it, though, that didn’t make sense. My understanding has always been that the College Board and ETS are separate entities; ETS has traditionally contracted to write the SAT. Why would the head of the College Board have the discretion to fire ETS employees?

I posted on the LinkedIn SAT prep teachers forum, where one tutor (and former ETS writer) with ETS contacts reported that she couldn’t get a straight answer out of anyone affiliated with that organization.

While trying to find more information online, I stumbled across “The Revenge of K-12,” by Richard Phelps and R. James Milgram, which confirmed that “house cleaning” did in fact occur. For those of who haven’t been following my blog, Jim Milgram is an emeritus professor of math at Stanford and one of two members of the Common Core validation committee who refused to sign off on the Standards; he has since co-authored a number of papers presenting in-depth critiques of the process by which they were created and implemented.

As Milgram and Phelps write:

Prior to Coleman’s arrival, competent and experienced testing experts suffused the College Board’s staff. But, rather than rely on them, Coleman appointed Cyndie Schmeiser, previously president of rival ACT’s education division, as College Board’s Director of Assessments. Schmeiser brought along her own non- psychometric advisors to supervise the College Board’s psychometric staff. While an executive at ACT, Schmeiser aided Coleman’s early standards- production effort from 2008–2010 by loaning him full-time ACT standards writers. (It should be no surprise, then, that many of the “college readiness” measures and conventions for CCS-aligned tests sound exactly like ACT’s.)

I was aware that Coleman had brought in a number of people from the ACT, but prior to reading the article, I had not realized that Coleman had brought in new, less qualified people to advise the psychometricians themselves. (This is hardly a surprise, though – as Coleman has indicated in the past, he’s not particularly interested in whether his hires are qualified.)

I emailed Jim Milgram, who told me that unfortunately he had no more information regarding who was writing the actual test than what I had turned up.

Then, a couple of days later, I happened to find myself at the house of a friend whose son is a junior. My friend wasn’t sure whether I’d seen this year’s practice PSAT booklet, so she made a point of showing it to me. I’d already seen the test, but as I looked over all the fine print, I realized I should check it for references to ETS. I couldn’t find any, which meant nothing in itself, but then something else occurred to me – perhaps I could compare this year’s booklet to previous years’ booklets and see whether those booklets contained references to ETS.

Sure, enough, at the bottom of the back page, previous years’ PSAT booklets contained a standard disclaimer stating that the views presented in the passages were not intended to reflect those of the College Board, the National Merit Corporation, or ETS.

This year’s booklet did not mention ETS.

Furthermore, references to the SAT on ETS’ website link back only to the current version of the test; aside from one mention of an ETS testing code, I could find no reference to ETS on any of the material intended for post-January 2016 use.

I realize that this is no way represents conclusive proof, but it does suggest that ETS is playing a less prominent role in the writing of the new test than it did in the old.

If it is in fact true that ETS is no longer writing the SAT, it would mark the end of a nearly 70-year relationship and create an even more radical break with the current exam than what has already been publicized.

SAT questions have always been written by a motley group – professional test-writers, teachers, even students – but they have also undergone an extensive, rigorous field-testing process closely supervised by people qualified to supervise it.

So if ETS is no longer responsible for writing the test (or assembling groups to write the test) and overseeing the test-writing process, then who is?

A group of test-writers handpicked/led by David Coleman? (We know how well his attempt at national standards-writing has been received.)

Former ACT writers and remaining College Board employees deemed sufficiently loyal to the Coleman regime?

Khan Academy employees?

Or, dare I say, it…might Pearson be somehow involved? (I really did think that was a stretch until I saw Dipti Desai’s graphic; I emailed her to ask what information she had about the connection, but I still haven’t heard back.)

Based on Milgram and Phelps’s report, it would certainly seem that regardless of who is writing the actual questions, the people supervising the process have far less expertise than those who did so in the past.

Furthermore, with the experimental section gone, there will no longer be a way for new questions to be tested out nationally on an actual group of test-takers. That absence of an experimental section is, I imagine, a significant part of the reason ACT scales can be so unpredictable; the questions just aren’t vetted as rigorously.

Say what you want about the SAT, but it is nothing if not consistent. It’s actually quite remarkable to watch a student take a test administered in 2007 and one administered in 2014 and get exactly the same score. In the absence of an experimental section, it’s hard to see how that kind of consistency will be retained.

In reality, though, the new test is not really the SAT at all. Call it a modified (ripped-off) ACT, a Common Core capstone exam, or just a grab for lost market share. The name is simply being retained because altering it would risk calling attention to the extremity of the changes and create too much potential for backlash.

Likewise, the return to the 1600 scoring scale is a carefully calculated distraction, designed to make adults think that the test will be closer to what it was when they were in high school and thus not to bother to investigate further.

Somehow, though, I wouldn’t be surprised if the same problems that have plagued other Common Core-aligned tests (PARCC, SBAC) start cropping up with the new SAT. Witness, for example, this discussion on College Confidential about determining cutoffs for National Merit. Somehow, I don’t recall so many pages of a thread ever being devoted to something so basic in the past. Elegance and transparency…right. And I’m guessing that this is only a warm-up for what’s to come.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 22, 2015 | Blog

I am happy to announce that my SAT and ACT books can now be purchased directly through this website. Selling directly now allows me to offer steep discounts off the Amazon list prices. Both domestic and international shipping are available. See the Books page for details.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 19, 2015 | Blog, Issues in Education

I stumbled across this little priceless little ditty left by SomeDAM Poet in the comments sections of this post on Diane Ravitch’s blog and felt compelled to repost it:

“Don’t drink the Colemanade”

Stop! Don’t drink the Colemanade!

The Coleman Core that Coleman made

What Coleman aided has culminated

In public schools calumniated

And to that I would add my own poetic two cents:

The Colemanade that Coleman made

Has percolated unallayed

In classrooms Coleman has created

His Standards march on, unabated

Now Coleman’s Core and Coleman’s aid

Do flow to schools now desiccated

The urgency must be conveyed

to clean the mess that Coleman made.

In all seriousness, though, anyone who’s even the least bit concerned about Common Core should read Diane’s post. And Lyndsey Layton’s article. And Mercedes Schneider’s book (both of them, actually).

I cannot overstate the importance of what these people have to say about public education in the United States right now.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 13, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT

If you’ve looked at the redesigned PSAT or SATs, you’ve probably noticed that the reading section now includes a number of “supporting evidence” sets — that is, pairs of questions in which the second question asks which lines provide the best “evidence” for the answer to the previous question.

The first thing to understand about these questions is that they are not really about “evidence” in the usual sense. Rather they are comprehension questions asked two different ways. The answer to the second question simply indicates where in the passage the answer the first question appears.

So although paired questions may look very complicated, that appearance is deceiving. The correct answer to the first question must appear in one of the four sets of lines in the second question. As a result, the easiest way to approach these questions is usually to plug the line references from the second question into the first question. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 3, 2015 | Blog, SAT Grammar (Old Test), The New SAT

So I’m in the middle of rewriting the workbook to The Ultimate Guide to SAT Grammar. After the finishing the new SAT grammar and reading books, I somehow thought that this one would be easier to manage. Annoying, yes, but straightforward, mechanical, and requiring nowhere near the same intensity of focus that the grammar and reading books required. Besides, I no longer have 800 pages worth of revisions hanging over me — that alone makes things easier.

However, having managed to get about halfway through, I have to say that I’ve never had so much trouble concentrating on what by this point should be a fairly rote exercise. Even writing three or four questions a day feels like pulling teeth. (So of course I’m procrastinating by posting here.)

In part, this is because I have nothing to build on. With the other two book, I was revising and/or incorporating material I’d already written elsewhere; this one I have to do from scratch. I’m also just plain sick and tired of rewriting material that I already poured so much into the first time around.

The problem goes beyond that, though. (more…)