by Erica L. Meltzer | Mar 9, 2016 | Blog

This is courtesy of a commenter on Diane Ravitch’s blog who goes by the handle RageAgainstTheTestocracy. I wish I could take credit for it, but alas, I’m just not that good. Definitely the funniest piece of Common Core commentary I’ve read since Akil Bello’s Skills, Skills, Skills.

All I can say is that David Coleman may have taken the humor out of the SAT, but at least he’s giving the people who follow the exploits of the tester-in-chief a field day.

Oh well, better to laugh than cry.

The Sorting Test

A thousand thoughts or more ago,

When I was newly known,

There lived four wizards of renown,

Whose names are still well-known:

Bold Billy Gates from Microsoft,

Fair Rhee from her DC stint,

Sweet Duncan from Down Under,

Lord Coleman from Vermint.

They shared a wish, a hope, a scheme,

They hatched a daring plan,

To test all children in the land,

Thus Common Core began.

Now each of these four founders

Stack ranked to find the best

They value just one aptitude,

In the ones they had to test.

By level 1, the lowest were

There just to detest;

For Level 2, the closest

But failed to be the best;

For Level 3, hard workers were

Barely worthy of admission;

And power-hungry Level 4s

Were those of great ambition.

While still alive they did divide

Their favorites from the throng,

Yet how to pick the worthy ones

When they were dead and gone?

‘Twas Coleman then who found the way,

He whipped me out of his head

The founders wrote the standards

So I could choose instead!

Now slip me snug around your brain,

I’ve never yet been wrong,

I’ll have a look inside your mind

And tell where you belong!”

by Erica L. Meltzer | Mar 6, 2016 | Blog, College Admissions

Frank Bruni wrote a column in yesterday’s The New York Times, in which he expounded on the virtues of college admission committees’ decisions to look past marginal test scores in a handful of underprivileged applicants in order to diversify their classes.

Depending on your perspective, what Bruni describes can either be construed as a noble undertaking or the symptom of a corrupt system that unfairly disadvantages hardworking, middle-class applicants, but I’m actually not concerned with that particular debate here.

Rather, my issue with Bruni’s column is that it perpetuates a common straw man argument in the debate over college admissions — namely, that test scores have traditionally been the be-all end-all of the admissions game, and that only now are a handful of intrepid admissions officers are willing to look past less-than-stellar scores and consider other aspects of a student’s application. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Mar 3, 2016 | Blog, SAT Reading

1) Start with your favorite passage(s)

You’re going to be sitting and reading for over an hour (well over an hour, if you count the Writing section), so you don’t want to blow all your energy on the first couple of passages. Take a few minutes at the start of the test, and see which passages seem easiest/most interesting, and which ones seem hardest/least interesting. Start with the easy ones, and end with the hard ones. This is not the ACT; you have plenty of time, and taking a few minutes to do this step can help you pace yourself more efficiently. You’ll get a confidence boost upfront, and you’ll be less likely to panic when you hit the harder stuff later on.

2) Be willing to skip questions

Unless you’re absolutely set on getting an 800 or close to it, you don’t need to answer every question — in fact, you probably shouldn’t (although you should always make sure to fill in answer for every question, since the quarter point wrong-answer penalty has been eliminated). If your first reaction when you look at a question is that you have no idea what it’s asking, that’s probably a sign you’re better off moving onto other things. That is particularly true on the Reading section because questions are not presented in order of difficulty. A challenging question can be followed by a very easy one, and there’s no sense getting hung up on the former if you can answer the latter quickly. And if you truly hate graph questions or Passage 1/Passage 2 relationship questions, for example, then by all means just skip them and be done with it.

3) Be willing to skip an entire passage

This might sound a little radical, but hear me out. It’s an adaptation of an ACT strategy that actually has the potential to work even better on the new SAT than it does on the ACT. This is especially true if you consistently do well on the Writing section; a strong score there can compensate if you are weaker in Reading, giving you a respectable overall Verbal score. Obviously this is not a good strategy if you are aiming for a score in the 700s; however, if you’re a slow but solid reader who is scoring in the high 500s and aiming for 600s, you might want to consider it.

Think of it this way: if four of the passages are pretty manageable for you but the fifth is very hard, or if you feel a little short on time trying to get through every passage and every question, this strategy allows you to focus on a smaller number of questions that you are more likely to answer correctly. In addition, you should pick one letter and fill it in for every question on the set you skip. Assuming that letters are distributed evenly as correct answers (that is, A, B, C, and D are correct approximately the same number of times on a given test, and in a given passage/question set), you will almost certainly grab an additional two or even three points.

If you’re not a strong reader, I highly recommend skipping either the Passage 1/Passage 2, or any fiction passages that include more antiquated language, since those are the passage types most likely to cause trouble.

4) Label the “supporting evidence” pairs before you start the questions

Although you may not always want to use the “plug in” strategy (plugging in the line references from the second question into the first question in order to answer both questions simultaneously), it’s nice to have the option of doing so. If you don’t know the “supporting evidence” question is coming, however, you can’t plug anything in. And if you don’t label the questions before you start, you might not remember to look ahead. This is particularly true when the first question is at the bottom of one page and the second question is at the top of the following page.

5) Don’t spend too much time reading the passages

You will never — never — remember every single bit of a passage after a single read-through, so there’s no point in trying to get every last detail. The most important thing is to avoid getting stuck in a reading “loop,” in which you re-read a confusing phrase or section of a passage multiple times, emerging with no clearer a sense of what it’s saying than when you began. This is a particular danger on historical documents passages, which are more likely to include confusing turns of phrase. Whatever you do, don’t fall into that trap! You will waste both time and energy, two things you cannot afford to squander upfront. Gently but firmly, force yourself to move on, focusing on the beginning and the end for the big picture. You can worry about the details when you go back.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Feb 29, 2016 | Blog, The New SAT

This just in: earlier today I met with a tutor colleague who told me that the College Board had sent emails to at least 10 of his New York-area colleagues who were registered for the first administration of the new SAT, informing them that their registration for the March 5th exam had been transferred to the May exam. Not coincidentally, the May test will be released, whereas the March one will not.

Another tutor had his testing location moved to, get this… Miami.

I also heard from another tutor in North Carolina whose registration was also transferred to May for “security measures.” Apparently this is a national phenomenon. Incidentally, the email she received gave her no information about why her registration had been cancelled for the March test. She had to call the College Board and wait 45 minutes on hold to get even a semi-straight answer from a representative. Along with releasing test scores on time, customer service is not exactly the College Board’s strong suit. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Feb 28, 2016 | Blog, The New SAT

The Washington Post reported yesterday that the new SAT will in fact continue to include an experimental section. According to James Murphy of the Princeton Review, guest-writing in Valerie Strauss’s column, the change was announced at a meeting for test-center coordinators in Boston on February 4th.

To sum up:

The SAT has traditionally included an extra section — either Reading, Writing, or Math — that is used for research purposes only and is not scored. In the past, every student taking the exam under regular conditions (that is, without extra time) received an exam that included one of these sections. On the new SAT, however, only students not taking the test with writing (essay) will be given versions of the test that include experimental multiple-choice questions, and then only some of those students. The College Board has not made it clear what percentage will take the “experimental” version, nor has it indicated how those students will be selected.

Murphy writes:

In all the public relations the company has done for the new SAT, however, no mention has been made of an experimental section. This omission led test-prep professionals to conclude that the experimental section was dead.

He’s got that right — I certainly assumed the experimental section had been scrapped! And I spend a fair amount of time communicating with people who stay much more in the loop about the College Board’s less publicized wheelings and dealings than I do.

Murphy continues:

The College Board has not been transparent about the inclusion of this section. Even in that one place it mentions experimental questions—the counselors’ guide available for download as a PDF — you need to be familiar with the language of psychometrics to even know that what you’re actually reading is the announcement of experimental questions.

The SAT will be given in a standard testing room (to students with no testing accommodations) and consist of four components — five if the optional 50-minute Essay is taken — with each component timed separately. The timed portion of the SAT with Essay (excluding breaks) is three hours and 50 minutes. To allow for pretesting, some students taking the SAT with no Essay will take a fifth, 20-minute section. Any section of the SAT may contain both operational and pretest items.

The College Board document defines neither “operational” nor “pretest.” Nor does this paragraph make it clear whether all the experimental questions will appear only on the fifth section, at the start or end of the test, or will be dispersed throughout the exam. During the session, I asked if all the questions on the extra section won’t count and was told they would not. This paragraph is less clear on that issue, since it suggests that experimental (“pretest”) questions can show up on any section.

When The Washington Post asked for clarification on this question, they were sent the counselor’s paragraph, verbatim. Once again, the terminology was not defined and it was not clarified that “pretest” does not mean before the exam, but experimental.

For starters, I was unaware that the term “pretest” could have a second meaning. Even by the College Board’s current standards, that’s pretty brazen (although closer to the norm than not).

Second, I’m not sure how it is possible to have a standardized test that has different versions with different lengths, but one set of scores. (Although students who took the old test with accommodations did not receive an experimental section, they presumably formed a group small enough not to be statistically significant.) In order to ensure that scores are as valid as possible, it would seem reasonable to ensure that, at bare minimum, as many students as possible receive the same version of the test.

As Murphy rightly points out, issues of fatigue and pacing can have a significant effect on students’ scores — a student who takes a longer test will, almost certainly, become more tired and thus more likely to incorrectly answers questions that he or should would otherwise have gotten right.

Second, I’m no expert in statistics, but there would seem to be some problems with this method of data collection. Because the old experimental section was given to nearly all test-takers, any information gleaned from it could be assumed to hold true for the general population of test-takers.

The problem now is not simply that only one group of testers will be given experimental questions, but that the the group given experimental questions and the group not given experimental questions may not be comparable.

If you consider that the colleges requiring the Essay are, for the most part, quite selective, and that students tend not to apply to those schools unless they’re somewhere in the ballpark academically, then it stands to reason that the group sitting for the Essay will be, on the whole, a higher-scoring group than the group not sitting for the Essay.

As a result, the results obtained from the non-Essay group might not apply to test-takers across the board. Let’s say, hypothetically, that test takers in the Essay group are more likely to correctly answer a certain question than are test-takers in the non-Essay group. Because the only data obtained will be from students in the non-Essay group, the number of students answering that question correctly is lower than it would be if the entire group of test-takers were taken into account.

If the same phenomenon repeats itself for many, or even every, experimental question, and new tests are created based on the data gathered from the two unequal groups, then the entire level of the test will eventually shift down — perhaps further erasing some of the score gap, but also giving a further advantage to the stronger (and likely more privileged) group of students on future tests.

All of this is speculation, of course. It’s possible that the College Board has some way of statistically adjusting for the difference in the two groups (maybe the Hive can help with that!), but even so, you have to wonder… Wouldn’t it just have been better to create a five-part exam and give the same test to everyone?

by Erica L. Meltzer | Feb 5, 2016 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

A couple of weeks ago, I posted a guest commentary entitled “For What It’s Worth,” detailing the College Board’s attempt not simply to recapture market share from the ACT but to marginalize that company completely. I’m planning to write a fuller response to the post another time; for now, however, I’d like to focus on one point that was lurking between in the original article but that I think could stand to be made more explicit. It’s pretty apparent that the College Board is competing very hard to reestablish its traditional dominance in the testing market – that’s been clear for a while now – but what’s less apparent is that it may not be a fair fight.

I want to take a closer look at the three states that the College Board has managed to wrest away from the ACT: Michigan, Illinois, and Colorado. All three of these states had fairly longstanding relationships with the ACT, and the announcements that they would be switching to the SAT came abruptly and caught a lot of people off guard. Unsurprisingly, they’ve also engendered a fair amount of pushback. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jan 23, 2016 | Blog

Here I was, all set for the SAT to take its final bow when, in a remarkable twist, it was announced that hundreds of testing centers would be closed and the January test postponed until Feb. 20th thanks to the blizzard about to descend on the east coast.

Given that it was 60 degrees on Christmas Day in New York City and that this is the first real snowfall of the year, I can’t help but find this to be an bizarrely coincidental turn of events. It would seem that the SAT is not about to go quietly.

That notwithstanding, tomorrow is still the last official SAT test date, and thus I feel obligated to post a few words in tribute to an exam that’s had a disproportionately large impact on my life over these last few years. (Full disclosure: I’m also posting this now because I’ve gone through the trouble of writing this post, and if I wait another month, I might get caught up in something and forget to post it.)

I’ll do my best not to get all mushy and sentimental.

From time to time, various students used to ask me hedgingly whether I loved the SAT. It was a reasonable question. After all, who would spend quite so much time tutoring and writing about a test they didn’t really, really like?

I can’t say, however, that I ever loved the SAT in a conventional sense. The test was something I happened to be good at more or less naturally (well, the verbal portion at least), and tutoring it was something I just happened to fall into. I didn’t start out with any particular agenda or viewpoint about the test; it was simply a necessary hurdle to be dealt with on the path to college, and as I saw it, my job was to make that hurdle as straightforward and painless as possible. To be sure, there were aspects of the tests that were genuinely interesting to discuss, and don’t even get me started on the let’s-use-Harry-Potter-examples-to-define-vocabulary-fests, but as I always told my students, “You don’t have to like it — you just have to take it.”

What I will say, though, is something I’ve heard from many tutors as well as from many students (and their parents), namely that after spending a certain amount of time grappling with the SAT, picking it apart and understanding its strengths as well as its shortcomings, you develop a sort of grudging respect for the test. For a lot of students, the SAT is the first truly challenging academic obstacle they’ve faced — the first test they couldn’t ace just by reading the Sparknotes version or programming their calculator with a bunch of formulas. For the students I tutored long-term, there was almost always a moment when it finally sank in: Oh. This test is actually difficult. I’m going to have to really work if I want to improve. And usually they rose to the challenge.

But the interesting part is that what started out as no more than a nuisance, another hoop to jump through on the way to college, could sometimes turn into a real educational experience — one that left them noticeably more comfortable reading college-level material, whether or not they got all the way to where they wanted to go. And when they did improve, sometimes to levels beyond what their parents had thought them capable of, their sense of accomplishment was enormous. They had fought for those scores. Perhaps I lack imagination, but I just don’t see students having those types of experiences quite as often with the new test.

That’s a best-case scenario, of course; I think the worst-case scenarios have been sufficiently rehashed elsewhere to make it unnecessary for me to go into all that here. But regardless of what you happen to think of the SAT, there’s a lot to be said for having the experience of wrestling with something just high enough above your level to be genuinely challenging but just close enough to be within reach.

This test has also led me down roads I never could have foreseen. While I’ve also been primarily interested in the SAT’s role as a cultural flashpoint, in the way it sits right at the crux of a whole host of social and educational issues, it’s also taught me more than I ever could have imagined about what constitutes effective teaching, how the reading process works, and about the gap between high school and college learning. And I’ve met a lot of (mostly) great people because of it, many of whom have become not only colleagues but also friends. I never thought I’d say this, but I owe the SAT a lot. It wasn’t a perfect test, but considered within the narrow confines of what it could realistically be expected to demonstrate, it did its job pretty well.

So on that note, I’m going to say something that might sound odd: to those of you taking this last test, consider yourselves lucky. Consider yourselves lucky to have been given the opportunity to take a test that holds you to an actual standard; that gives you a snapshot of the type of vocabulary and reading that genuinely reflect what you’ll encounter in college; that isn’t designed to pander to your ego by twisting the numbers until they’re all but meaningless.

And if you’ve been granted a reprieve for tomorrow, enjoy the snow day and catch up on your sleep.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jan 20, 2016 | Blog, The New SAT

Update #2 (1/27/16): Based on the LinkedIn job notification I received yesterday, it seems that ETS will be responsible for overseeing essay grading on the new SAT. That’s actually a move away from Pearson, which has been grading the essays since 2005. Not sure what to think of this. Maybe that’s the bone the College Board threw to ETS to compensate for having taken the actual test-writing away. Or maybe they’re just trying to distance themselves from Pearson.

Update: Hardly had I published this post when I discovered recent information indicating that ETS is still playing a consulting role, along with other organizations/individuals, in the creation of the new SAT. I hope to clarify in further posts. Even so, the information below raises a number of significant questions.

Original post:

Thanks to Akil Bello over at Bell Curves for finally getting an answer:

(In case the image is too small for you to read, the College Board’s Aaron Lemon-Strauss states that “with rSAT we manage all writing/form construction in-house. use some contractors for scale, but it’s all managed here now.” You can also view the original Twitter conversation here.)

Now, some questions:

What is the nature of the College Board’s contract with ETS?

Who exactly is writing the actual test questions?

Who are these contractors “used for scale,” and what are their qualifications? What percentage counts as “some?”

What effect will this have on the validity of the redesigned exam? (As I learned from Stanford’s Jim Milgram, one of the original Common Core validation committee members, many of the College Board’s most experienced psychometricians have been replaced.)

Are the education officials who are mandated the redesigned SAT in Connecticut, Michigan, Colorado, Illinois, and New York City aware that the test is no longer being written by ETS?

Why has this not been reported in the media? I cannot recall a single article, in any outlet, about the rollout of the new test that even alluded to this issue. ETS has been involved in writing the SAT since the 1940s. It is almost impossible to overstate what a radical change this is.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jan 18, 2016 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

For those of you who haven’t been following the College Board’s recent exploits, the company is in the process of staging a massive, national attempt to recapture market share from the ACT. Traditionally, a number of states, primarily in the Midwest and South, have required the ACT for graduation. Over the past several months, however, several states known for their longstanding relationships with the ACT have abruptly – and unexpectedly – announced that they will be dropping the ACT and mandating the redesigned SAT. The following commentary was sent to me by a West Coast educator who has been closely following these developments.

For What It’s Worth

On December 4, 2015 a 15-member evaluation committee met in Denver, Colorado to begin the process of awarding a 5-year state testing contract to either the ACT, Inc. or the College Board. After meeting three more times (December 10, 11, and 18th) the evaluation committee awarded the Colorado contract to the College Board on December 21, 2015. The committee’s meetings were not open to the public and the names of the committee members were not known until about two weeks later.

Once the committee’s decision became public, parents complained that it placed an unfair burden on juniors who had been preparing for the ACT. Over 150 school officials responded by sending a protest letter to Interim Education Commissioner Elliott Asp. The letter emphasized the problem faced by juniors and also noted that Colorado would be abandoning a test for which they had 15 years of data for a new test with no data. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jan 17, 2016 | Blog, The New SAT

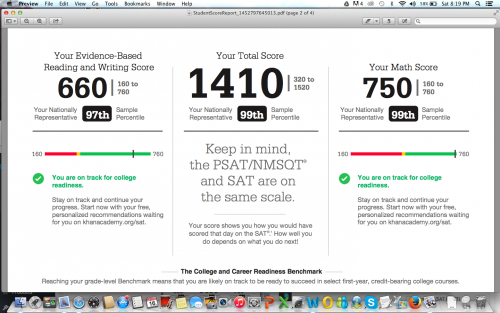

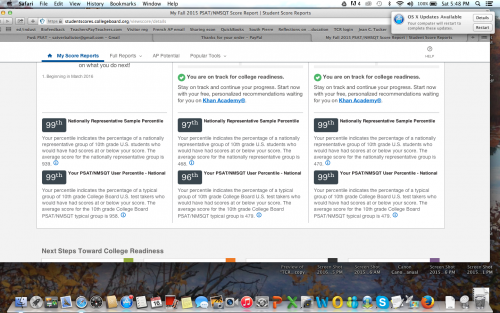

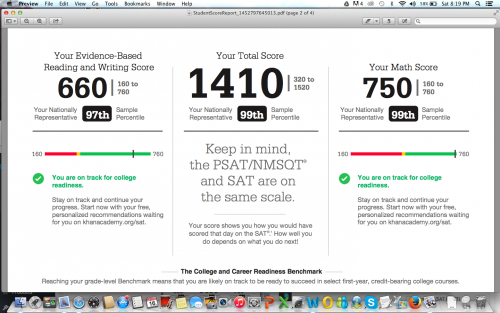

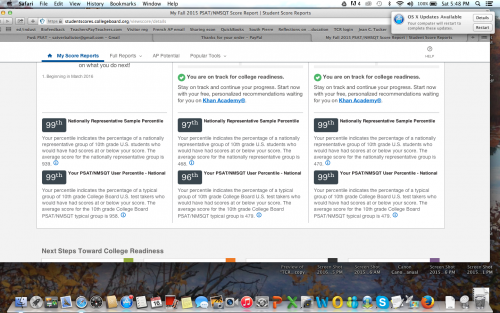

A couple of posts back, I wrote about a recent Washington Post article in which a tutor named Ned Johnson pointed out that the College Board might be giving students an exaggeratedly rosy picture of their performance on the PSAT by creating two score percentiles: a “user” percentile based on the group of students who actually took the test; and a “national percentile” based on how the student would rank if every 11th (or 10th) grader in the United States took the test — a percentile almost guaranteed to be higher than the national percentile.

When I read Johnson’s analysis, I assumed that both percentiles would be listed on the score report. But actually, there’s an additional layer of distortion not mentioned in the article.

I stumbled on it quite by accident. I’d seen a PDF-form PSAT score report, and although I only recalled seeing one set of percentiles listed, I assumed that the other set must be on the report somewhere and that I simply hadn’t noticed them.

A few days ago, however, a longtime reader of this blog was kind enough to offer me access to her son’s PSAT so that I could see the actual test. Since it hasn’t been released in booklet form, the easiest way to give me access was simply to let me log in to her son’s account (it’s amazing what strangers trust me with!).

When I logged in, I did in fact see the two sets of percentiles, with the national, higher percentile of course listed first. But then I noticed the “download report” button, and something occurred to me. The earlier PDF report I’d seen absolutely did not present the two sets of percentiles as clearly as the online report did — of that I was positive.

So I downloaded a report, and sure enough, only the national percentiles were listed. The user percentile — the ranking based on the group students who actually took the test — was completely absent. I looked over every inch of that report, as well as the earlier report I’d seen, and I could not find the user percentile anywhere.

Unfortunately (well, fortunately for him, unfortunately for me), the student in question had scored extremely well, so the discrepancy between the two percentiles was barely noticeable. For a student with a score 200 points lower, the gap would be more pronounced. Nevertheless, I’m posting the two images here (with permission) to illustrate the difference in how the percentiles are reported on the different reports.

Somehow I didn’t think the College Board would be quite so brazen in its attempt to mislead students, but apparently I underestimated how dirty they’re willing to play. Giving two percentiles is one thing, but omitting the lower one entirely from the report format that most people will actually pay attention to is really a new low.

I’ve been hearing tutors comment that they’ve never seen so many students obtain reading scores in the 99th percentile, which apparently extends all the way down to 680/760 for the national percentile, and 700/760 for the user percentile. Well…that’s what happens when a curve is designed to inflate scores. But hey, if it makes students and their parents happy, and boosts market share, that’s all that counts, right? Shareholders must be appeased.

Incidentally, the “college readiness” benchmark for 11th grade reading is now set at 390. 390. In contrast, the I confess: I tried to figure out what that corresponds to on the old test, but looking at the concordance chart gave me such a headache that I gave up. (If anyone wants to explain it me, you’re welcome to do so.) At any rate, it’s still shockingly low — the benchmark on the old test was 550 — as well as a whopping 110 points lower than the math benchmark. There’s also an “approaching readiness” category, which further extends the wiggle room.

A few months back, before any of this had been released, I wrote that the College Board would create a curve to support the desired narrative. If the primary goal was to pave the way for a further set of reforms, then scores would fall; if the primary goal was to recapture market share, then scores would rise. I guess it’s clear now which way they decided to go.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jan 12, 2016 | Blog

Then apparently you’re not alone.

I was under the impression that all PSAT scores had been finally released on 1/7, at least until I happened to check Mercedes Schneider’s blog. Apparently, some students are still unable to access their scores (or at least they were as of 1/9).

According to one Pennsylvania parent Schneider cites:

As of today, more than 24 hours after the scores were supposedly released yesterday, we are still unable to see them. I have been advised by a school counselor that this is also happening to [several other] top ranked [Pennsylvania] high schools. There may be many others here and around the country, because when parents/students call the College Board to complain, the PSAT help line (866-433-7728) is so profoundly overloaded that a recorded message comes on advising to try to call again tomorrow or after going through a series of prompts hangs up or puts people into an endless cue. I just reached an agent after holding for nearly an hour. The agent looked into my teen’s account and confirmed that no October 2015 scores have been released and that access codes for …many high schools have not been delivered. She offered to “escalate” my concern to another department, which she said would respond in 5-7 business days, which is outrageous.

If this is widespread, College Board is in deep crisis. If it is just [our area in our state], then our students are being placed at a disadvantage compared to other students in terms of preparation for the March SAT. In any case, College Board has demanded that it hold the key to the futures of millions of children, but it is increasingly showing that is unworthy of such a great trust and responsibility.

You can read the entire post here.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jan 10, 2016 | Blog, The New SAT

Apparently I’m not the only one who thinks the College Board might be trying to pull some sort of sleight-of-hand with scores for the new test.

In this Washington Post article about the (extremely delayed) release of 2015 PSAT scores, Ned Johnson of PrepMatters writes:

Here’s the most interesting point: College Board seems to be inflating the percentiles. Perhaps not technically changing the percentiles but effectively presenting a rosier picture by an interesting change to score reports. From the College Board website, there is this explanation about percentiles:

Percentiles

A percentile is a number between 0 and 100 that shows how you rank compared to other students. It represents the percentage of students in a particular grade whose scores fall at or below your score. For example, a 10th-grade student whose math percentile is 57 scored higher or equal to 57 percent of 10th-graders.

You’ll see two percentiles:

The Nationally Representative Sample percentile shows how your score compares to the scores of all U.S. students in a particular grade, including those who don’t typically take the test.

The User Percentile — Nation shows how your score compares to the scores of only some U.S. students in a particular grade, a group limited to students who typically take the test.

What does that mean? Nationally Representative Sample percentile is how you would stack up if every student took the test. So, your score is likely to be higher on the scale of Nationally Representative Sample percentile than actual User Percentile.

On the PSAT score reports, College Board uses the (seemingly inflated) Nationally Representative score, which, again, bakes in scores of students who DID NOT ACTUALLY TAKE THE TEST but, had they been included, would have presumably scored lower. The old PSAT gave percentiles of only the students who actually took the test.

For example, I just got a score from a junior; 1250 is reported 94th percentile as Nationally Representative Sample percentile. Using the College Board concordance table, her 1250 would be a selection index of 181 or 182 on last year’s PSAT. In 2014, a selection index of 182 was 89th percentile. In 2013, it was 88th percentile. It sure looks to me that College Board is trying to flatter students. Why might that be? They like them? Worried about their feeling good about the test? Maybe. Might it be a clever statistical sleight of hand to make taking the SAT seem like a better idea than taking the ACT? Nah, that’d be going too far.

I’m assuming that last sentence is intended to be taken ironically.

One quibble. Later in the article, Johnson also writes that “If the PSAT percentiles are in fact “enhanced,” they may not be perfect predictors of SAT success, so take a practice SAT.” But if PSAT percentiles are “enhanced,” who is to say that SAT percentiles won’t be “enhanced” as well?

Based on the revisions to the AP exams, the College Board’s formula seems to go something like this:

(1) take a well-constructed, reasonably valid test, one for which years of data collection exists, and declare that it is no longer relevant to the needs of 21st century students.

(2) Replace existing test with a more “holistic,” seemingly more rigorous exam, for which the vast majority of students will be inadequately prepared.

(3) Create a curve for the new exam that artificially inflates scores.

(4) Proclaim students “college ready” when they may be still lacking fundamental skills.

(5) Find another exam, and repeat the process.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 29, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT

Among the partial truths disseminated by the College Board, the phrase “guessing penalty” ranks way up there on the list of things that irk me most. In fact, I’d say it’s probably #2, after the whole “obscure vocabulary” thing.

Actually, calling it a partial truth is generous. It’s actually more of a distortion, an obfuscation, a misnomer, or, to use a “relevant” word, a lie.

Let’s deconstruct it a bit, shall we?

It is of course true that the current SAT subtracts an additional ¼ point for each incorrect answer. While this state of affairs is a perennial irritant to test-takers, not to mention a contributing factor to the test’s reputation for “trickiness,” it nevertheless serves a very important purpose – namely, it functions as a corrective to prevent students from earning too many points from lucky guessing and thus from achieving scores that seriously misrepresent what they actually know. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 27, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT

In a Washington Post article describing the College Board’s attempt to capture market share back from the ACT, Nick Anderson writes:

Wider access to markets where the SAT now has a minimal presence would heighten the impact of the revisions to the test that aim to make it more accessible. The new version [of the SAT], debuting on March 5, will eliminate penalties for guessing, make its essay component optional and jettison much of the fancy vocabulary, known as “SAT words,” that led generations of students to prepare for test day with piles of flash cards.

Nick Anderson might be surprised to discover that “jettison” is precisely the sort of “fancy” word that the SAT tests.

But then again, that would require him to do research, and no education journalist would bother to do any of that when it comes to the SAT. Because, like, everyone just knows that the SAT only tests words that no one actually uses. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 26, 2015 | Blog, SAT Essay, The New SAT

For the last part in this series, I want to consider the College Board’s claim that the redesigned SAT essay is representative of the type of assignments students will do in college.

Let’s start by considering the sorts of passages that students are asked to analyze.

As I previously discussed, the redesigned SAT essay is based on the rhetorical essay from the AP English Language and Composition (AP Comp) exam. While they comprise a wide range of themes, styles, and periods, the passages chosen for that test are usually selected because they are exceptionally interesting from a rhetorical standpoint. Even if the works they are excerpted from would most likely be studied in their social/historical context in an actual college class, it makes sense to study them from a strictly rhetorical angle as well. Different types of reading can be appropriate for different situation, and this type of reading in this particular context is well justified.

In contrast, the texts chosen for analysis on the new SAT essay are essentially the type of humanities and social science passages that routinely appear on the current SAT – serious, moderately challenging contemporary pieces intended for an educated general adult audience. To be sure, this type of writing is not completely straightforward: ideas and points of views are often presented in a manner that is subtler than what most high school readers are accustomed to, and authors are likely to make use of the “they say/I say” model, dialoguing with and responding to other people’s ideas. Most students will in fact do a substantial amount of this type of reading in college.

By most academic standards, however, these types of passages would not be considered rhetorical models. It is possible to analyze them rhetorically – it is possible to analyze pretty much anything rhetorically – but a more relevant question is why anyone would want to analyze them rhetorically. Simply put, there usually isn’t all that much to say. As a result, it’s entirely unsurprising that students will resort to flowery, overblown descriptions that are at odds with actual moderate tone and content of the passages. In fact, that will often be the only way that students can produce an essay that is sufficiently lengthy to receive a top score.

There are, however, a couple of even more serious issues.

First, although the SAT essay technically involves an analysis, it is primarily a descriptive essay in the sense that students are not expected to engage with either the ideas in the text or offer up any ideas of their own. With exceedingly few exceptions, however, the writing that students are asked to do in college with be thesis-driven in the traditional sense – that is, students will be required to formulate their own original arguments, which they then support with various pieces of specific evidence (facts, statistics, anecdotes, etc.) Although they may be expected to take other people’s ideas into account and “dialogue” with them, they will generally be asked to do so as a launching pad for their own ideas. They may on occasion find it necessary to discuss how a particular author presents his or her evidence in order to consider a particular nuance or implication, but almost never will they spend an entire assignment focusing exclusively on the manner in which someone else presents an argument. So although the skills tested on the SAT essay may in some cases be a useful component of college work, the essay itself has virtually nothing to do with the type of assignments students will actually be expected to complete in college.

By the way, for anyone who wants understand the sort of work that students will genuinely be expected to do in college, I cannot recommend Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein’s They Say/I Say strongly enough. This is a book written by actual freshman composition instructors with decades of experience. Suffice it to say that it doesn’t have much to do with what the test-writers at the College Board imagine that college assignments look like.

Now for the second point: the “evidence” problem.

As I’ve mentioned before, the SAT essay prompt does not explicitly ask students to provide a rhetorical analysis; rather, it asks them to consider how the writer uses “evidence” to build his or her argument. That sounds like a reasonable task on the surface, but it falls apart pretty quickly once you start to consider its implications.

When students do the type of reading that the SAT essay tests in college, it will pretty much always be in the context of a particular subject (sociology, anthropology, economics, etc.). By definition, non-fiction is both dependent on and engaged with the world outside the text. There is no way to analyze that type of writing meaningfully or effectively without taking that context into account. Any linguistic or rhetorical analysis would always be informed by a host of other, external factors that pretty much any professor would expect a student to discuss. There is a reason that “close reading” is normally associated with fiction and poetry, whose meanings are far less dependent on outside factors. Any assignment that asks students to analyze a non-fiction author’s use of evidence without considering the surrounding context is therefore seriously misrepresenting what it means to use evidence in the real world.

In college and in the working world, the primary focus is never just on how evidence is presented, but rather how valid that evidence is. You cannot simply present any old facts that happen to be consistent with the claim you are making – those facts must actually be true, and any competent analysis must take that factor into account. The fact that professors and employers complain that students/employees have difficulty using evidence does not mean that the problem can be solved just by turning “evidence” into a formal skill. Rather, I would argue that the difficulties students and employees have in using evidence effectively is actually a symptom of a deeper problem, namely a lack of knowledge and perhaps a lack of exposure to (or an unwillingness to consider) a variety of perspectives.

If you are writing a Sociology paper, for example, you cannot simply state that the author of a particular study used statistics to support her conclusion, or worse, claim that an author’s position is “convincing” or “effective,” or that it constitutes a “rich analysis” because the author uses lots of statistics as evidence. Rather, you are responsible for evaluating the conditions under which those statistics were gathered; for understanding the characteristics of the groups used to obtain those statistics; and for determining what factors may not have been taken into account in the gathering of those statistics. You are also expected to draw on socio-cultural, demographic, and economic information about the population being studied, about previous studies in which that population was involved, and about the conclusions drawn from those studies.

I could go on like this for a while, but I think you probably get the picture.

As I discussed in my last post, some of the sample essays posted by the College Board show a default position commonly adopted by many students who aren’t fully sure how to navigate the type of analysis the new SAT essay requires – something I called “praising the author.” Because the SAT is such an important test, they assume that any author whose work appears on it must be a pretty big. As a result, they figure that they can score some easy points by cranking up the flattery. Thus, authors are described as “brilliant” and “passionate” and “renowned,” even if they are none of those things.

As a result, the entire point of the assignment is lost. Ideally, the goal of close reading is to understand how an author’s argument works as precisely as possible in order to formulate a cogent and well-reasoned response. The goal is to comprehend, not to judge or praise. Otherwise, the writer risks setting up straw men and arguing in relation to positions that they author does not actually take.

The sample essay scoring, however, implies something different and potentially quite problematic. When students are rewarded for offering up unfounded praise and judgments, they can easily acquire the illusion that they are genuinely qualified to evaluate professional writers and scholars, even if their own composition skills are at best middling and they lack any substantial knowledge about a subject. As a result, they can end up confused about what academic writing entails, and about what is and is not appropriate/conventional (which again brings us back to They Say/I Say).

These are not theoretical concerns for me; I have actually tutored college students who used these techniques in their writing.

My guess is that a fair number of colleges will recognize just how problematic an assignment the new essay is and deem it optional. But that in turn creates an even larger problem. Colleges cannot very well go essay-optional on the SAT and not the ACT. So what will happen, I suspect, is that many colleges that currently require the ACT with Writing will drop that requirement as well – and that means highly selective colleges will be considering applications without a single example of a student’s authentic, unedited writing. Bill Fitzsimmons at Harvard came out so early and so strongly in favor of the SAT redesign that it would likely be too much of an embarrassment to renege later, and Princeton, Yale, and Stanford will presumably continue to go along with whatever Harvard does. Aside from those four schools, however, all bets are probably off.

If that shift does in fact occur, then no longer will schools be able to flag applicants whose standardized-test essays are strikingly different from their personal essays. There will be even less of a way to tell what is the result of a stubborn 17 year-old locking herself in her room and refusing to show her essays to anyone, and what is the work of a parent or an English teacher… or a $500/hr. consultant.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 18, 2015 | Blog, SAT Essay, The New SAT

In response to my previous post on the equity issues surrounding the redesigned SAT essay, one reader had this to say:

I read a few of the essay prompts and honestly they seem like a joke. Essentially, each prompt asked for the exact same thing, it’s almost like CB is just screaming “MAKE A TEMPLATE” because all students need to do is plug in the author’s name, cite an example, and put a quote here and there and if it’s surrounded by prepared fancy sentences, they’ve got an easy 12. (or whatever it is now)

That’s a fair point. I didn’t actually mean to imply in my earlier post that students would actually need to be experts in rhetoric in order to score well – my goal was primarily to point out the mismatch between the background a student would need to seriously be able to complete the assignment, and the sort of background the most students will actually bring to the assignment.

For a good gauge of what is likely to happen, consider the French AP exam, which was revised a couple of years ago to be more holistic and “relevant.” It now includes a synthesis essay that is well beyond what most AP French students can write. The result? Score inflation. A similar phenomenon is inevitable here: when there is such a big mismatch between ideal and reality, the only way for the College Boart to avoid embarrassment and promote the illusion that students are actually doing college-level work is assign high scores to reasonably competent work that does not actually demonstrate mastery but that throws in a few fancy flourishes, and solid passing scores to work that is only semi-component.

So I agree halfway. Something like what the reader describes is probably going to be a pretty reliable formula, albeit one that many students will need tutoring to figure out. But that said, I suspect that it will be one for churning out solid, mid-range essays, not top-scoring ones. Here’s why:

While looking through the examples provided by the College Board, I noticed something interesting: out of all the essays, exactly one made extensive use of “fancy” rhetorical terminology (anecdote, allusion, pathos, dichotomy). Would you like to guess which one? If you said the only essay to earn top scores in each of the three rubric categories, you’d be right.

What this suggests to me is that the redesigned essay will in fact be vulnerable to many of the same “inflation” techniques that many high-scoring students already employ. As Katherine Beals and Barry Garelick’s recent Atlantic article discussed, the only way to assess learning is to look for “markers” typically associated with comprehension/mastery. A problem arises, however, when the goal becomes solely to exhibit the markers of mastery without actually mastering anything – and standardized test- essays are nothing if not famous for being judged on markers of mastery rather than on substance.

The current SAT essay, of course, has been criticized for encouraging fake “fancy” writing – bombastic, flowery prose stuffed full of ten-dollar words, and there is absolutely nothing to suggest that this will change. In fact, the new essay is likely to encourage that type of writing just as much, if not more, than the old one.

Indeed, the top-scoring examples include some truly cringe-worthy turns of phrase. For example, consider one student’s statement that “This dual utilization of claims from two separate sources conveys to Gioia’s audience the sense that the skills built through immersion in the arts are vital to succeeding in the modern workplace which aids in logically leading his audience to the conclusion that a loss of experience with the arts may foreshadow troubling results.”

Not to mention this: “In paragraph 5, Gioia utilizes a synergistic reference to two separate sources of information that serves to provide a stronger compilation of support for his main topic” (https://collegereadiness.collegeboard.org/sample-questions/essay/2, last example).

And this: “In order to achieve proper credibility and stir emotion, undeniable facts must reside in passage.”

This is the sort of prose that makes freshman (college) composition instructors tear their hair out. Is this what the College Board means by “college readiness?”

Furthermore, if the use of fancy terminology correlates with high scores, why not exploit that correspondence and simply pump out essays stuffed to the gills with exotic terms, with little regard for whether they describe what is actually occurring in the text? As long as the description is sufficiently flowery, those sorts of details are likely to slip by unnoticed.

In fact, why not go a step further and simply make up some Greek-sounding literary terms? Essay graders are unlikely to spend more than the current two minutes scoring essays; they don’t have the time or the liberty to check whether obscure rhetorical terms actually exist. Some really smart kids with a slightly twisted sense of humor will undoubtedly decide to have some fun at the College Board’s expense. Heck, if I could force myself to wake up at 6 a.m. on a Saturday morning, I’d be tempted to go and do it myself.

Another observation: as discussed in an earlier post, one of the key goals of the SAT essay redesign was to stop students from making up information. But even that seems to have failed: lacking sufficient background information about the work they are analyzing, students will simply resort to conjecture. For example, the writer of the essay scoring 4/3/4 states that Bogard (the author of the first sample passage) is “respected,” and that “he has done his research.” Exactly how would the student know that Bogard is “respected?” Or that he even did research? (Maybe he just found the figures in a magazine somewhere.) Or that the figures he cites are even accurate?

It is of course reasonable to assume those things are true, but strictly speaking, the student is “stepping outside the four corners of the text” and making inferences that he or she cannot “prove” objectively. So despite the College Board’s adamant insistence that essays rely strictly on the information provided in the passages, the inclusion of these sorts of statements in a high-scoring sample essay certainly suggests that the boundary between “inside” and “outside” the text is somewhat more flexible than it would appear.

The point, of course, is that it is extraordinarily difficult, if not downright impossible, to remain 100% within the “four corners” of a non-fiction text and still write an analysis that makes any sense at all – particularly if one lacks the ability to identify a wide range of rhetorical figures. Of course students will resort to making up plausible-sounding information to pad their arguments. And based on the sample essays, it certainly seems that they will continue to be rewarded for doing so.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 13, 2015 | Blog, SAT Essay, The New SAT

In my previous post, I introduced some of background issues surrounding the new SAT essay. Here, I’d like to examine to examine how the redesigned essay, rather than make the SAT a fairer test as the College Board claims, will likely provide further advantages to a small, already privileged segment of the test-taking population.

Let’s start with the fact that the new essay was adapted from the rhetorical essay on the AP English Language and Composition (AP Comp) exam.

To be sure, the colleges that require the essay are likely to draw many applicants enrolled in AP Comp as juniors, but there will still undoubtedly be tens of thousands of students sitting for the SAT essay who are not enrolled in AP Comp, or whose schools do not even offer that class. Many other students whose schools do offer AP Comp may not take it until senior year, well after they’ve taken their first SAT. And then there will be students who are enrolled in AP Comp as juniors but who spend class talking in small groups with their classmates and not ever being taught about rhetorical analysis. (Based on my own experience tutoring AP Comp, I suspect that many students fall into that last category.) What sort of value is there in asking so many students to write an essay that they are totally unprepared to write?

The College Board, of course, has attempted to make the essay appear more egalitarian by insisting that no particular terminology or background knowledge is required, and that students can find all the information they need in the passage. Whereas the AP Comp prompt explicitly asks students to analyze the rhetorical choices…an author makes in order to develop her/her argument, the College Board deliberately avoids use of the term “rhetoric” for the SAT essay, opting for the more neutral “evidence and reasoning” and stylistic or persuasive elements,” and giving the impression that the assignment is wide open by asserting that students may also analyze features of [their] own choice.

The problem is that this type of formal, written textual analysis is a highly artificial task. It involves a very particular type of abstract thought, one that really only exists in school. (I suspect that the only American students seriously studying rhetoric at a high level are budding classicists at a handful of very, very elite mostly private schools – a minuscule percentage of test-takers.) Learning to notice, to divide, to label, to categorize, to enter into a text and describe the order and logic by which it functions… These are not instinctive ways of reading; learning to do these things well takes considerable practice. If students don’t acquire this particular skill set in school, and more particularly in English class, they almost certainly won’t acquire it anywhere else. Of all the things tested on the new SAT, this is the one Khan Academy is least equipped to handle.

It also strikes me as naïve and more than a little bit misleading to insist that this type of analysis can be performed by any old student if the technical aspect is removed – that is, if students write “appeal to emotion” rather than pathos. Yes, it is possible to write a top-scoring essay that employs nothing but plain old Anglo-Saxon words, but in most cases, the students most capable of even faking their way through a rhetorical analysis will be precisely the ones who have learned the formal terms. Students don’t somehow acquire skills simply from being allowed to express themselves in non-technical language.

The choice to adopt this particular template for the SAT essay was, I imagine, based on the presumption that Common Core would sweep through classrooms across the United States, with all students spending their English periods diligently practicing for college and career readiness by combing through non-fiction passages, finding “evidence” (the text means what it means because it says what it says) and identifying “appeals to emotion and authority.”

Needless to say, that reality has not materialized; however, the SAT is based on the assumption that it would.

So whereas smart, solid writers who didn’t do much of anything in English class had as good a chance as anyone else at doing well on the pre-2016 essay, smart, solid writers who have not been given practice in this particular type of writing in English class will now be at a much larger disadvantage. There will of course be the extreme outliers who can sit themselves down with a prep book, read over a few examples, and start churning out flawless expository prose, but they will be the exceptions that prove the rule.

As for the rest, well… let’s just say the new essay is basically the College Board’s gift to the tutoring industry.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 9, 2015 | Blog, SAT Essay, The New SAT

In the past, I haven’t posted much about the SAT essay. Even though my students always did well, teaching the SAT essay was never my favorite part of tutoring, in large part because I’m what most people would consider a natural writer (thanks in large part to the 5,000 or so books I consumed over the course of my childhood), and “naturals” don’t usually make the best teachers. Besides, teaching someone to write is essentially a question of teaching them to think, and that’s probably the only thing harder than teaching someone to read.

The redesigned essay is a little different, first because it directly concerns the type of rhetorical analysis that so much of my work focuses on. In theory, I should like it a lot. At the same time, though, it embodies some of the most problematic aspects of the new SAT for me. Some of these issues recur throughout the test but seem particularly thorny here.

I’ve been trying to elucidate my thoughts about the essay for a long time; for some reason, I’m finding it exceptionally difficult to disentangle them. Every point seems mixed up with a dozen other points, and every time I start to go in one direction, I inevitably get tugged off in a different one. For that reason, I’ve decided to devote multiple posts to this topic. That way, I can keep myself focused on a limited number of ideas at a time and avoid writing a post so long that no one can get more than halfway through!

Before launching into an examination of the essay itself, some background.

First, it is necessary to understand that the major driving force behind the essay change is the utter lack of correlation between factual accuracy and scores – that is, the rather embarrassing fact that students are free to invent examples (personal experiences, historical figures/battles/act, novels, etc.) without penalty. In particular, personal examples have been a particular target of David Coleman’s ire because they cannot be assessed “objectively.” The College Board simply could not withstand any more bad publicity for that particular shortcoming. As a result, it was necessary to devise a structure that would simultaneously require students to use “evidence” yet not require – or rather appear not to require – any outside knowledge whatsoever.

As I’ve pointed out before, students have been – and still are – perfectly free to make up examples on the ACT essay, but for some mysterious reason, the ACT never seems to take the kind of flack that the SAT does. Again, marketing.

My feelings on this issue have evolved somewhat over the years; they’re sufficiently complex to merit an entire post, if not more, so for now I’ll leave my opinion out of this particular aspect of the discussion.

Let’s start with the pre-2016 essay.

Despite its very considerable shortcomings, the current SAT essay is as close as possible to a pure exercise in “using evidence” – or at least in supporting a claim with information consistent with that claim (information that may or may not be factually accurate), which is essentially the meaning of “evidence” that the College Board itself has chosen to adopt.

For all its pseudo-philosophical hokeyness, the current SAT essay does at least represents an attempt to be fair. The questions are deliberately constructed to be so broad that anyone, regardless of background, can potentially find something to say about them. (Are people’s lives the result of the choices they make? Can knowledge be a burden rather than a benefit?). Furthermore, students are free to support their arguments with examples from any area they choose – contrary to popular belief, there is ample room for creativity.

While students may, if they so choose, use personal examples, the top-scoring essays tend to use examples from literature, history, science, and current events. The example of a top-scoring essay in the Official Guide, if memory serves me correctly, is an analysis of the factors leading up to the stock market crash of 1929 – not exactly a personal narrative. In contrast, essays that rely on personal examples, particularly invented ones, tend to be vague, unconvincing, and immature. Yes, there are some students who can pull that type of fabrication off with aplomb, but in most cases, “can” does not mean “should.”

Furthermore, students who make up facts to support other types of examples are rarely able to do so convincingly. The ones who can are, by definition, strong writers who understand how to bullshit effectively – a highly useful real-world skill, it should be pointed out. But in general, the best writers tend to have strong knowledge bases (both being the result of a good education) and thus the least need to make up facts.

That is why the essay, formerly part of the Writing SAT II test, was relatively uncontroversial for most of its existence: only selective colleges required it, and so only the students who took it were students applying to selective college – a far, far smaller number than apply today. As prospective applicants to selective colleges, those-test takers were generally taking very rigorous classes and thus had very a solid academic base from which to draw. Remember that this was also in the days before work could be copied and pasted from Wikipedia, and when AP classes were still mostly restricted to very top students. While plenty of smart-alecks (including, I should confess, me) did of course invent examples, the phenomenon was considerably more limited than it became in 2005, when the essay was tacked on to the SAT-I.

Based on what I’ve witnessed, I suspect that the questionable veracity of many current essays is also a result of the reality that many students who attempt to write about books, historical events, scientific examples, etc. simply do not know enough facts to support their arguments effectively, either because they are not required to learn them at all in school (the acquisition of factual knowledge being dismissed as “rote memorization” or “mere facts”), or because information is presented in such a fragmentary, disorganized manner that they lack the sort of mental framework that would allow them to retain the facts they do learn.

One of the unfortunate consequences of doing away with lectures, I would argue, is that students are not given the sort of coherent narratives that tend to facilitate the retention of factual information. (Yes, they can read or watch online lectures, but there’s no substitute for sitting in a room with a real, live person who can sense when a class is confused and back up or adjust an explanation accordingly.)

At any rate, when word got out about just how ridiculous some of those top-scoring essays were… Well, the College Board had a public relations problem on its hands. The essay redesign was thus also prompted by the need to remove the factual knowledge component.

Now, here it gets interesting. As I forgot until recently, the GRE “analyze an argument” essay actually solves the College Board’s problem quite effectively. (The GMAT and LSAT also have similar essays.) Test-takers are presented with a brief argument, either in the form of a letter to an editor, a summary of research in a magazine or journal, or a pitch for a new business. While the exact prompt can vary slightly, it is usually something along the lines of this: Write a response in which you discuss what specific evidence is needed to evaluate the argument and explain how the evidence would weaken or strengthen the argument.

The beauty of the assignment is that it has clearly defined parameters – there is effectively no way for students to go outside the bounds of the situation described – yet allows for considerable flexibility. The situations are also general and neutral enough that no specific outside knowledge, terminology, or coursework is necessary to evaluate arguments concerning them.

In short, it is a solid, fair, well-designed task that reveals a considerable amount about students’ ability to think logically, present and organize their ideas in writing, evaluate claims/evidence, and “dialogue” with differing points of view while still maintaining a clear focus on their own argument.

There is absolutely no reason this assignment could not have been adapted for younger students. It would have eliminated any temptation for students to invent (personal) examples while providing an excellent snapshot of analytical writing ability and remaining more or less universally accessible. It also would have been perfectly consistent with the redesigned exam’s focus on “evidence.”

Instead, the College Board essentially created a diluted rhetorical strategy essay, taken from the AP English Composition exam — a very specific, subject-based essay that many students will lack prior experience writing. Students are given 50 minutes (double the current 25) to read a passage of about 750 words in response to the following prompt:

As you read the passage below, consider how the author uses

- evidence, such as facts or examples, to support claims.

- reasoning to develop ideas and to connect claims and evidence.

- stylistic or persuasive elements, such as word choice or appeals to emotion, to add power to the ideas expressed.

Write an essay in which you explain how the author builds an argument to persuade his/her audience that xxx. In your essay, analyze how the author uses one or more of the features in the directions that precede the passage (or features of your own choice) to strengthen the logic and persuasiveness of his/her argument. Be sure that your analysis focuses on the most relevant features of the passage.

Your essay should not explain whether you agree with the author’s claims, but rather explain how the author builds an argument to persuade his/her audience.

Before I go any further, I want to make something clear: I am not in any way opposed to asking students to engage closely with texts, or to analyzing how authors construct their arguments, or to requiring the use of textual evidence to support one’s arguments. Most of my work is devoted to teaching people to do these very things.

What I am opposed to is an assignment that directly contradicts claims of increased equity by testing skills only a small percentage of test-takers have been given the opportunity to acquire; that misrepresents the amount and type of knowledge needed to complete the assignment effectively; and that purports to reflect the type of work that students will do in college but that is actually very far removed from what the vast majority of actual college work entails.

In my next post, I’ll start to look at these issues more closely.