by Erica L. Meltzer | Nov 8, 2015 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

I’ve been doing some more pondering about the claims of increased equity attached to the new SAT, and although I’m still trying to sift through everything, I’ve at least managed to put my finger on something that’s been nagging at me.

Basically, the College Board is now espousing two contradictory views: on one hand, it trumpets things like the inclusion of “founding documents” in order to proclaim that the SAT will be “more aligned with what students are doing in school,” and on the other hand, it insists that no particular outside knowledge is necessary to do well on the reading portion of the exam.

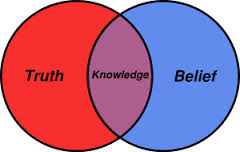

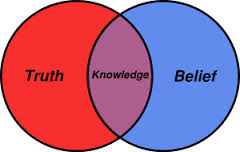

While that assertion may contain a grain of truth – some very strong readers with just enough background knowledge will be able to able to navigate the test without excessive difficulty – it is also profoundly disingenuous. Comprehension can never be completely divorced from knowledge, and even middling readers students who have been fed a steady diet of “founding documents” in their APUSH classes will be at a significant advantage over even strong readers with no prior knowledge of those passages.

You really can’t have it both ways. If background knowledge truly isn’t important and the SAT is designed to be as close to a pure reading test as possible, then every effort should be made to use passages that the vast majority of students are unlikely to have already seen. (That perspective, incidentally, is the basis for the current SAT.)

On the flip side, a test that is truly intended to be aligned with schoolwork can only be fair if everyone taking the test is doing the same schoolwork – a virtual impossibility in the United States. That’s not a bug in the system, so to speak; it is the system. Even if Common Core had been welcomed with open arms, there would still be a staggering amount of variation.

To state what should be obvious, it is impossible to design an exam that is aligned with “what students are learning in school” when even students in neighboring towns – or even at two different schools in the same town – are doing completely different things. Does anyone sincerely think that students in public school in the South Bronx are doing the same thing as those at Exeter? Or, for that matter, that students in virtual charter schools in Mississippi are doing the same things as those in public school in Scarsdale? Yet all of these students will be taking the exact same test.

The original creators of the SAT were perfectly aware of how dramatically unequal American education was; they knew that poorer students would, on the whole, score below their better-off peers. Their primary goal was to identify the relatively small number of students from modest backgrounds who were capable of performing at a level comparable to students at top prep schools. Knowing that the former had not been exposed to the same quality of curriculum as the latter, they deliberately designed a test that was as independent as possible from any particular curriculum.

So when people complain that the SAT doesn’t reflect, or has somehow gotten away from, “what students are doing in school,” they are, in some cases very deliberately, missing the whole point – the test was never intended to be aligned with school in the first place. Given the American attachment to local control of education, that was not an irrational decision. (Although I somehow doubt they could have ever imagined the industry, not to mention the accompanying stress, that would eventually grow up around the exam.)

Viewed in this light, the attempt to create a school-aligned SAT can actually be seen as a step backwards – one that either dramatically overestimates the power of Common Core to standardize curricula, or that simply turns a blind eye to very substantial differences in the type of work that students are actually doing in school.

The problem is even more striking on the math side than on the verbal. As Jason Zimba, who led the Common Core math group, admitted, Common Core math is not intended to go beyond Algebra II, yet the SAT math section will now include questions dealing with trigonometry – a subject to which many juniors will not yet have been exposed. (For more about the problems with math on the new exam, see “The Revenge of K-12: How Common Core and the New SAT Lower College Standards in the U.S.” as well as “Testing Kids on Content They’ve Never Learned” by blogger Jonathan Pelto.) In that regard, the new SAT is even more misaligned with schoolwork than the reading. The current exam, in contrast, does not go beyond Algebra II – the focus is on material that pretty much everyone taking a standard college-prep program has covered.

The unfortunate reality is that disparities in test scores reflect larger educational disparities; it’s a lot easier to blame a test than to address underlying issues, for example the relationship between tax dollars and public school funding. Yes, the test plays a role in the larger system of inequality, but it is one factor, not the primary cause. Any nationally-administered exam, whatever it happens to be called, will to some extent reflect the gap (unless, of course, you start with the explicit goal of engineering a test on which everyone can do well and work backwards to create an exam that ensures that outcome).

Assuming, however, that the goal is not to design an exam that everyone aces, then there’s no obvious way out of the impasse. Create an exam that isn’t tied to any particular curriculum, and students are forced to take time away from school to prepare. Create an exam that’s “curriculum-based,” and you inevitably leave out huge numbers of students since there’s no such thing as a standard curriculum.

Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 19, 2015 | Blog, Issues in Education

I stumbled across this little priceless little ditty left by SomeDAM Poet in the comments sections of this post on Diane Ravitch’s blog and felt compelled to repost it:

“Don’t drink the Colemanade”

Stop! Don’t drink the Colemanade!

The Coleman Core that Coleman made

What Coleman aided has culminated

In public schools calumniated

And to that I would add my own poetic two cents:

The Colemanade that Coleman made

Has percolated unallayed

In classrooms Coleman has created

His Standards march on, unabated

Now Coleman’s Core and Coleman’s aid

Do flow to schools now desiccated

The urgency must be conveyed

to clean the mess that Coleman made.

In all seriousness, though, anyone who’s even the least bit concerned about Common Core should read Diane’s post. And Lyndsey Layton’s article. And Mercedes Schneider’s book (both of them, actually).

I cannot overstate the importance of what these people have to say about public education in the United States right now.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 27, 2015 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

Passage 1 is excerpted from a speech about the Common Core State Standards given by David Coleman at the senior leadership meeting at the University of Pittsburgh’s Institute of Learning in 2011. Passage 2 is from Sandra Stotsky’s June 2015 Testimony regarding Common Core, delivered at Bridgewater State University. Stotsky was a member of the Common Core validation committee who, along with R. James Milgram, refused to sign off on the Standards. Student Achievement Partners is a company founded by David Coleman that played a significant role in developing Common Core.

Passage 1

Student Achievement Partners, all you need to know about us are a couple of things. One is that we’re composed of that collection of unqualified people who were involved in developing the common standards. And our only qualification was our attention to and command of the evidence behind them. That is, it was our insistence in the standards process that it was not enough to say you wanted to or thought that kids should know these things, that you had to have evidence to support it, frankly because it was our conviction that the only way to get an eraser into the standards room was with evidence behind it, ‘cause otherwise the way standards are written you get all the adults into the room about what kids should know, and the only way to end the meeting is to include everything. That’s how we’ve gotten to the typical state standards we have today. (Mercedes Schneider, Common Core Dilemma, 2015, p. 2440 Kindle ed.) (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 19, 2015 | Blog, Issues in Education

On the surface, everyone’s favorite buzzword certainly seems unobjectionable enough. In addition to being short, snappy, and alliterative (all good qualities in a buzzword), who could possibly argue that high school students shouldn’t be prepared for college and careers? When you consider the slogan a bit more closely, however, it starts to make a little less sense.

First and most obviously, the American higher education system is staggeringly diverse, encompassing everything from for-profit trade schools to community colleges to state flagship institutions to the Ivy League. While it seems reasonable to assume that there is a baseline skills that all (or most) students should be expected to graduate from high school, a one-size-fits-all approach makes absolutely no sense when it comes to college admissions.

Does anyone seriously think that a student who wants to study accounting at a local community college and one who wants to study physics at MIT should come out of high school knowing the same things? Or that a student who wants to study communications through an online, for-profit college and a student who wants to study philosophy at Princeton should be expected to read at the same level? A student receiving straight A’s at one institution could easily need substantial remediation to even earn a passing grade at the other. Viewed this way, the definition of “college readiness” as “knowledge and skills in English and mathematics necessary to qualify for and succeed in entry-level, credit-bearing post-secondary coursework without the need for remediation” is effectively meaningless.

Second, let’s consider the “career readiness” part. Perhaps this was less true when the slogan was originally coined (by the ACT…I think), but today it is more or less impossible to obtain even the lowest-level white collar position without a college diploma. Virtually anyone entering the job market immediately after high school will almost certainly be considered only for service jobs (flipping burgers, stocking shelves at Walmart) or manual labor. While these jobs do require basic literacy and numeracy skills, they are light years away from those required by even a relatively un-challenging college program. It makes no sense to group them with post-secondary education.

Third, the pairing of “college and career” is more than a little problematic. While there are obviously some skills that translate well in both the classroom and in the boardroom (writing clearly and grammatically, organizing one’s thoughts in a logical manner, considering multiple viewpoints), there are other ways in which the skills valued in the classroom (searching for complexity, “problematizing” seemingly straightforward ideas) are exactly the opposite of those usually prized in the working world. They are enormously valuable skills, but on their own merits. It really only makes sense to lump college and work together in this way if you are attempting to redefine college as quasi-trade school for the tech industry.

Like most people, though, I assumed that the “college” part was intended refer to traditional, four-year institutions. Then, while reading one of the white papers released by Ze’ev Wurman and Sandra Stotsky (one of the writers of the 1998 Massachusetts ELA standards, considered the most rigorous in the country, and one of only two members of the Common Core validation committee to refuse to sign off on the standards), I came across this edifying tidbit:

The clearest statement of the meaning of [college and career readiness] that we have found appears in the minutes of the March 23 meeting of the Massachusetts Board of Elementary and Secondary Education. Jason Zimba, a member of the mathematics draft-writing team who had been invited to speak to the Board, stated, in response to a query, that “the concept of college readiness is minimal and focuses on non- selective colleges.” Earlier, Cynthia Schmeiser, president and CEO of ACT’s Education Division, one of Common Core’s key partners, testified to a U.S. Senate Committee that college readiness was aimed at such post-secondary institutions as “two- or four-year colleges, trade schools, or technical schools.” These candid comments raise professional and ethical issues. The concept is apparently little more than a euphemism for “minimum competencies,” the concept that guided standards and tests in the 1980s, with little success in increasing the academic achievement of low-performing students…

Moreover, it seems that this meaning for college readiness was intended only for low-achieving high school students who are to be encouraged to seek enrollment in non-selective post-secondary institutions. Despite its low academic goals and limited target, this meaning for college readiness was generalized as the academic goal for all students and offered to the public without explanation. (Stotsky and Wurman, “The Emperor’s New Clothes: National Assessments Based on Weak “College and Career Readiness Standards,” 2010.)

Stotsky goes on to point out that not a single detail from the very explicit standards laid out in the 2003 report “Understanding University Success” — a report that included input from 400 faculty members from 20 institutions, including Harvard, MIT, and the University of Virginia — was included in the Common Core Standards.

In contrast, Common Core standards were primarily written by 24 people, many of whom were affiliated with the testing industry, and some of whom had no teaching experience whatsoever. As Mercedes Schneider points out, Jason Zimba, the lead writer of the math standards:

…acknowledge[d] that ending with the Common Core in high school could preclude students from attending elite colleges. In many cases, the Core is not aligned with the expectations at the collegiate level. “If you want to take calculus your freshman year in college, you will need to take more mathematics than is in the Common Core.”

Likewise, I would add that analytical skills a tad more sophisticated than simply comparing and contrasting, or using evidence to support one’s arguments, are a prerequisite for doing any sort of serious university-level work in the humanities or social sciences. As is vocabulary beyond the level of synthesize and hypothesis.

Food for thought, the next time you hear/see Common Core described as a set of “more rigorous” (hah!) standards designed to prepare students for colleges and the workforce.”

Cynthia Schmeiser, incidentally, now works for the College Board. It’s amazing how, when you do a little prodding (or, should I say, “delve deep,” to invoke another preferred euphemism), the same names keep cropping up over and over again…

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 14, 2015 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

Carol Burris weighs in on the suggestion that the recent decline in SAT scores is due a more diverse pool of test-takers:

From the Washington Post:

Since 2011, average SAT scores have dropped by 10 points even though the proportion of test takers from the reported economic brackets has stayed the same and the modest uptick in the number of Latino students was partially offset by an increase in Asian American and international students [who have higher than average scores]. And in the year of the biggest drop (7 points), the proportional share of minority students is the same as it was in 2014. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 28, 2015 | Blog, Issues in Education

But claiming that there is apparently makes for a good headline.

Knowledge and skills are intertwined; unless schools start acknowledging that critical thinking can only result from detailed content knowledge, conversations about what’s ailing American education will continue to be an exercise in nonsense.

The fact that anyone can use the phrase “knowledge-based learning” in a non-ironic way creeps me out to no end.

What’s next? Word-based reading? Number-based math? Language-based speech?

I don’t believe Common Core is really going to change many things here. It’s a set of skills; it does not lay out a coherent, specific body of knowledge. The ELA standards, at least, are so vague and repetitive as to be virtually meaningless, and would be met automatically in any rigorous traditional classroom headed by a knowledgeable, well-trained teacher.

If school districts use CC to implement a more content-rich curriculum, that is their choice. Requiring students to learn any particular set of facts, no matter how anodyne, is so politically contentious that no one would dare attempt such a thing at the national level.

Writing in the New York Times, Natalie Wexler acknowledges that:

…engineering the switch from skills to knowledge will take real effort. Schools will need to develop coherent curriculums and adopt different ways of training teachers and evaluating progress. Because the federal government can’t simply mandate a focus on knowledge, change will need to occur piecemeal, at the state, school district or individual school level.

To believe that such a change could miraculously occur “piecemeal” goes far beyond wishful thinking and into the realm of pure fantasy. And no, the fact that a bunch of people have downloaded a free online curriculum isn’t exactly going to compensate. Poor scores on CC tests are unlikely to simply “incentivize” low-income schools to shift over to a stronger emphasis on subject content, especially if their curriculums are effectively centered around test-prep. Besides, doing things in such a haphazard fashion is a pretty great way to ensure that huge disparities (geographic, economic, etc.) continue to exist.

When you take a crop of teachers indoctrinated by ed schools to believe that lecturing and memorization are forms of child abuse; pair them with administrators who use the threat of poor evaluations to keep less progressive teachers in line; and mix in an obsession with testing and accountability, you end up with a chaotic system driven by quick fixes. (But hey, no worries, the market will sort it out, right?)

In order for the focus to shift more towards teaching content, you need a critical mass of people who believe that subject knowledge is the basis for critical thinking, both in the classroom and in the administrative offices. Right now, those people are in pretty short supply. And with the number of people entering teaching dwindling, the chance of getting highly educated/knowledgeable/competent teachers, who believe even partially in the importance of transmitting knowledge, in front of classrooms on any sort of wide scale in the near future is pretty small.

The Right isn’t exactly helping here either. Rather than embrace what would actually be a conservative concept of education (classical curriculum, back-to-basics, etc.), they’re too busy screaming about school choice and privatizing everything.

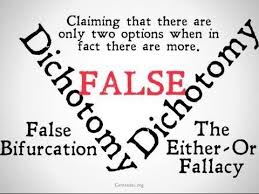

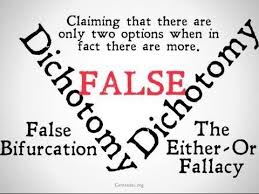

It’s a perfect storm of factors, and while everyone is busy setting up false dichotomies and waiting for technology to save the day, the descent into chaos continues.

I think a commenter named Emile from NY said it best:

I don’t know in depth the various pedagogical theories about K-12 education, but from the perspective of a college professor who’s been teaching at a mid-tier university for more than 25 years, K-12 education has been in a steady decline over the past few decades, and [E.D.] Hirsch is absolutely right about the reason for it.

I ask everyone in K-12 education this: What should a college professor who is teaching a course on Enlightenment ideas do in the face of a whole class of intelligent freshmen who don’t know the dates of the Civil War, or the Second World War, or the French Revolution, or know that once upon a time there was a Roman Empire? How, exactly, would you proceed? Or how, exactly, would you proceed in a basic college course in mathematics when faced with a college class of intelligent freshmen that can’t, as a whole, move easily between fractions, decimals and percents?

People hate the word “memorization,” but I’m here to tell you students love it. People who malign memorization often ask, “Why should anyone memorize dates that they’re bound to forget?” Not every date is remembered over the long haul, but the mind loves inductive reasoning, and has a way of gathering particular dates loosely into centuries, and from there building a kind of organized closet into which more knowledge can be added.

I’m not suggesting that first graders need to be able to able to discourse in detail about ancient Mesopotamia, but seriously, is it that unreasonable for college students to be expected to have a basic understanding of what happened in the past?