by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 3, 2015 | Blog, SAT Grammar (Old Test), The New SAT

So I’m in the middle of rewriting the workbook to The Ultimate Guide to SAT Grammar. After the finishing the new SAT grammar and reading books, I somehow thought that this one would be easier to manage. Annoying, yes, but straightforward, mechanical, and requiring nowhere near the same intensity of focus that the grammar and reading books required. Besides, I no longer have 800 pages worth of revisions hanging over me — that alone makes things easier.

However, having managed to get about halfway through, I have to say that I’ve never had so much trouble concentrating on what by this point should be a fairly rote exercise. Even writing three or four questions a day feels like pulling teeth. (So of course I’m procrastinating by posting here.)

In part, this is because I have nothing to build on. With the other two book, I was revising and/or incorporating material I’d already written elsewhere; this one I have to do from scratch. I’m also just plain sick and tired of rewriting material that I already poured so much into the first time around.

The problem goes beyond that, though. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 29, 2015 | ACT English/SAT Writing, Grammar (SAT & ACT), SAT Grammar (Old Test), Uncategorized

Nouns

Nouns are the most common type of subjects. They include people, places, and things and can be concrete (book, chair, house) or abstract (belief, notion, theory).

Example: Bats are able to hang upside down for long periods because they possess specialized tendons in their feet.

Pronouns

Pronouns are words that replace nouns. Common pronouns include she, he, it, one, you, this, that, and there.

Less common pronouns include what, how, whether, and that, all of which are singular. They are typically used as part of a much longer complete subject (underlined in the second example below).

Example: They are able to hang upside down for long periods because they possess specialized tendons in their feet.

Example: How bats hang upside down for long periods was a mystery until it was discovered that they possess specialized tendons in their feet.

Gerunds

Gerunds are formed by adding -ING to the ends of verbs (e.g. read – reading; talk – talking). Although gerunds look like verbs, they act like nouns. They are always singular and take singular verbs.

Example: Hanging upside down for long periods is a skill that both bats and sloths possess.

Infinitives

The infinitive is the “to” form of a verb. Infinitives are always singular when they are used as subjects. They are most commonly used to create the parallel structure “To do x is to do y.”

Example: To hang upside down for a long period of time is to experience the world as a bat or sloth does.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 23, 2015 | ACT English/SAT Writing, Blog, SAT Grammar (Old Test)

Shortcut: semicolon + and/but = wrong

If you see an answer choice on either the SAT or the ACT that places a semicolon before the word and or but, cross out that answer immediately and move on.

Why? Because a semicolon is grammatically identical to a period, and you shouldn’t start a sentence with and or but.

The slightly longer explanation: In real life, semicolon usage is a little more flexible, and the choice to use when can sometimes be more a matter of clarity/style than one of grammar. It is generally considered acceptable to place a semicolon before and or but in order to break up a very long sentence, especially when there are already multiple commas/clauses.

For example:

Pamela Meyer, a certified fraud examiner, author, and entrepreneur, became interested in the science of deception at business school workshop during which a professor detailed his findings on behaviors associated with lying; and she subsequently worked with a team of researchers to survey and analyze existing research on deception from academics, experts, law enforcement, the military, espionage and psychology.

In the above sentence, either a comma or a semicolon could be used before and. In this case, however, the sentence is so long and contains so many different parts that the semicolon is a logical choice to create stronger break between the parts.

Why not just use a period? Well, because a semicolon implies a stronger connection between the clauses than a period would; it keeps the sentence going rather than marking a full break between thoughts. Again, this is a matter of style, not grammar.

The SAT and the ACT, however, are not interested in these details. Rather, their goal is to check whether you understand the most common version of the rule. Anything beyond that would simply be too ambiguous.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jul 25, 2015 | Blog, SAT Grammar (Old Test)

So after months of living under a rock in a desperate attempt to finish my revised SAT books in time for the summer stampede, I’m finally taking a few tentative steps into the sunlight.

Several of you have written to me lamenting my lack of acerbic commentary on the June SAT scoring scandal, the new SAT, and other educational embarrassments, and I promise you that I am well aware of that shortcoming. Rest assured that I do in fact have many, many things to say; I’ve merely had to devote every last brain cell to rewriting my books for the last half-year, leaving me precious little room for other thoughts, acerbic or otherwise. I’m hoping to begin posting some commentary here in the next weeks.

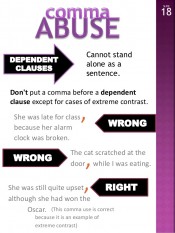

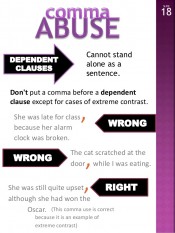

For the moment, though, I want to address a topic that a couple of people have written to me about recently, namely the “no comma before ‘because’ or ‘since’ rule.”

Actually, it’s not really a “rule” per se. It’s more of a guideline. In the universe of SAT grammar errors, it’s a pretty minor one, and for that reason it’s pretty certain that an answer’s correctness/incorrectness will never depend exclusively on it. It’s merely a secondary consideration.

Let me back up and explain.

There are two main types of conjunction: coordinating and subordinating.

Coordinating conjunctions (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so) are also known by the acronym FANBOYS. They can be used to join two independent clauses (complete sentences) and must always follow a comma when employed in this way.

Correct: The city’s government has curtailed spending on all non-essential services, so the new theater company has been forced to suspend its productions for lack of funding.

A FANBOYS conjunction can only be used at the start of the second clause; it cannot be used at the start of the first. Even if you don’t know the grammatical rule, you should be able to recognize that this usage does not make any sense.

Incorrect: So the new theater company has been forced to suspend its productions for lack of funding, the city’s government has curtailed spending on all non-essential services.

Subordinating conjunctions on the other hand, can be used to start either the first or the second clause. Common subordinating conjunctions include because, while, since, when, until, and unless.

Now, here’s the rub. If you are being absolutely, technically correct, a comma should be used to separate two clauses when the clause begun by the subordinating conjunction comes first.

Correct: Because/Since the city’s government has curtailed spending on all non-essential services COMMA the new theater company has been forced to suspend its productions for lack of funding.

When the clause begun by the subordinating conjunction comes second, no comma should be used (although there is an exception for “strong” subordinating conjunctions such as although and even though, which do take a comma).

Incorrect: The new theater company has been forced to suspend its productions for lack of funding COMMA because/since the city’s government has curtailed spending on all non-essential services.

Correct: The new theater company has been forced to suspend its productions for lack of funding NO COMMA because/since the city’s government has curtailed spending on all non-essential services.

That’s the strict version of the rule. The more complicated truth is that it depends on context: if a sentence is very long, or it seems necessary to insert a comma before because in order to make the meaning of the sentence clear, then that construction is acceptable.

From what I’ve observed, the College Board/ETS/whoever it is setting the rules tends to adhere to the strict version: answers that contain the construction comma + because/since are pretty much always wrong. (Please note that this pattern was observed in regards to the pre-2016 SAT only.)

That said, wrong answers with that construction almost always contain an additional problem that makes them absolutely, incontrovertibly wrong. So maybe it’s more correlation, not causation.

A while back, someone contacted me about a question in the online program that violated that rule; an answer with the construction comma + because was correct. That did make me rethink things, but only up to a point. I’ve found slight inconsistencies between the online tests and real tests in the past, and I’ve never seen a question from an administered test that broke this “rule” (although if anyone reading this post has seen one, please let me know!).

My suggestion, therefore, is to work from the standpoint that any answer with the construction comma + because/since is probably wrong, and only reevaluate that assumption if there’s a clear grammatical problem with every other answer. To be fair, the SAT does break its own “rules” sometimes, and this one isn’t particularly hard and fast. But still, you’re better off playing the odds and working from there.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jul 6, 2014 | Blog, SAT Grammar (Old Test)

Perhaps you’ve heard the saying “when you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.” If you’re not familiar with the expression, it means that when searching for an explanation, you should always consider obvious possibilities before thinking about more unlikely options. Whenever I tutor the Writing section of the SAT, I find myself uttering these words with inordinate frequency.

I’ve worked with a number of students trying to pull their Writing scores from the mid-600s to the 750+ range. Most have done well on practice tests but then unexpectedly seen their scores drop on the actual test. Unsurprisingly, they were puzzled by their performance on the real thing; they just couldn’t figure out what they had done differently. And at first glance, they did seem to know what they were doing. When I worked very carefully through a section with them, however, some cracks inevitably emerged. Not a lot, mind you, but just enough to consistently pull them down. They would be sailing along, identifying errors like there was no tomorrow, when all of the sudden they would hit a question whose error (if any) they simply could not identify.

When that happened, they would stop and read the sentence again. And when they couldn’t hear anything wrong, they would read the sentence again, slowly, trying to hear whether something was wrong (mistake #1). Then, if they really didn’t want to choose “No error” but weren’t sure whether something was truly wrong, they would start searching for an explanation, usually a somewhat convoluted one, for why a perfectly acceptable construction was ambiguous or awkward or otherwise wrong (mistake #2). Almost always they did so when the actual answers — answers based on concepts they understood perfectly well — were staring them right in the face.

One of things that it’s easy to forget — or, in the case of many natural high-scorers who haven’t needed to study the framework of the test, to never realize — is that “hard” questions are not necessarily hard because they test hard concepts. Most often, they are hard either because they test (relatively) simple concepts in hard ways or because they combine concepts in unexpected ways.

Hard questions can — and often do — have “easy” answers. That does not mean that the answer is the option that sounds weird (that’s the distractor answer). It does, however, mean that the answer is likely to be an extremely simple word like “is” or “are” or “it.” It also means that the answer probably involves an extremely common error, like subject verb agreement or pronoun agreement, not some obscure rule you’ve never heard of.

The challenge is figuring out which concept is being tested, not understanding the concept itself. So when people who can usually hear the error come across a question whose answer they don’t instantly hear, their instinctive reaction is to look for something outlandish to be wrong with it, not to think systematically about what the most common errors are and check to see whether the question contains them. In others words, they hear hoofbeats and imagine that a herd of zebras is about to come racing around the corner.

For example, consider the following question, which a very high-scoring student of mine recently missed:

(A) Thanks to the strength (B) of the bonds between (C) its

constituent carbon atoms, a diamond has exceptional

physical properties (D) that makes it useful in a wide

variety of industrial applications. (E) No error

If you spotted the error immediately, great, but bear with me for illustrative purposes. The sentence itself is rather challenging: it discusses a topic (chemistry) that many students are unlikely to have unpleasant associations with, and it also contains the word “constituent,” which many weaker readers will have difficulty decoding, and whose meaning many slightly stronger readers will not know or be able to figure out. So right there we have two big stumbling blocks likely to distract from the grammar of the sentence. Many test-takers are also likely to think that “Thanks to” sounds too casual and would be considered wrong on a serious test like the SAT. Many other test-takers are likely to just not hear any error.

In that case, the most effective approach is to consider the structure of the test. The most common error is subject-verb agreement, and when in doubt, it’s the error you should always check first. There is exactly one underlined verb in the sentence: “makes.” It singular (remember: singular verbs ends in “-s”), which means that it’s subject must be singular as well.

But what is the subject? “Physical properties,” which is plural, so there’s a disagreement. The answer is therefore (D). The sentence should read “…physical properties that make it useful.”

The moral of the story is that if you don’t spot an error immediately, whatever you do, don’t fall into the loop of endlessly rereading the sentence and trying to figure out whether something sounds funny. Instead, check systematically for the top five or so errors: subject-verb agreement, pronoun agreement (check “it” and “they”), verb tense (pay attention to dates and “time” words), adjectives vs. adverbs (easy to overlook), and, if you’re at the end of a section, faulty comparisons.

If all of those things check out, the sentence is probably fine.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jun 4, 2013 | Blog, SAT Grammar (Old Test)

I spend a lot of time teaching people to stop looking so hard at the details. Not that details are so bad in and of themselves — it’s just that they’re not always terribly relevant. There’s a somewhat infamous SAT Critical Reading passage that deals with the qualities that make for a good physicist, and since the majority of high school students don’t have particularly positive associations with that subject, most of them by extension tend to dislike the passage.

The remarkable thing is, though, that the point of the passage is essentially the point of the SAT: the mark of a good physicist is the ability to abstract out all irrelevant information.

Likewise, the mark of a good SAT-taker is the ability to abstract out all unimportant information and focus on what’s actually being asked.

One of the things that people tend to forget is that the SAT is an exam about the big picture — for Writing as well as Reading.

I say this because very often smart, detail-oriented students have a tendency to worry about every single thing that sounds even remotely odd or incomprehensible, all the while missing something major that’s staring them in the face. Frequently, they blame this on the fact that they’ve been taught in school to read closely and pay attention to all the details (and because they can’t imagine that their teachers could be wrong, they conclude that the SAT is a “stupid” test).

Well, I have some news: not all books are the kind you read in English class, and different kinds of texts and situations call for different kinds of reading. When find yourself in college social sciences class with a 300 page reading assignment that you have two days to get through, you won’t have time to annotate every last detail — nor will your professors expect you to do so. Your job will be to get the big picture and perhaps focus on one or two areas that you find particularly interesting so that you can show up with something intelligent to say.

But back to the SAT.

On CR, it’s fairly common for people to simply grind to a halt in passage when they encounter an unfamiliar turn of phrase. For example, most people aren’t quite accustomed to hearing the word “abstract” used as a verb: the ones who ignore that fact and draw a logical conclusion about its meaning from the context are generally fine. The other ones, the ones who can’t get past the fact that “abstract” is being used in a way they haven’t seen before, tend to run into trouble. They read it and realize they haven’t quite understood it. So they go back and read it again. They still don’t quite get it, so they reread it yet again. And before they know it, they’ve wasted two or three minutes just reading the same five lines over and over again.

Then they run out of time and can’t answer all of the questions.

The problem is that ETS will always deliberately choose passages containing bits that aren’t completely clear — that’s part of the test. The goal is to see whether you can figure out their meaning from the general context of the passage; you’re not really expected to get every word, especially not the first time around. The trick is to train yourself to ignore things that are initially confusing and move on to parts that you do understand. If you get a question about something you’re not sure of, you can always skip over it, but you should never get hung up on something you don’t know at the expense of something you can understand easily. If you really get the gist, you can figure a lot of other things out, whereas if you focus on one little detail, you’ll get . . . one little detail.

The question of relevant vs. irrelevant plays out a lot more subtly in the Writing section, where people often aren’t quite sure just what it is they’re supposed to be looking for, especially when it comes to Error-IDs. As a result, they want to understand the rule behind every underlined word and phrase, regardless of whether it’s something that’s really relevant. And because about 95% of the rules tested are predictable and fixed from one test to the next, a lot of the time the correct answers aren’t terribly relevant. Worrying about every little rule makes the grammar being tested appear much more complex than it actually is.

The reality is that if you only look for errors involving subject verb agreement, pronoun agreement, verb tense/form, parallel structure, logical relationships and comparisons, prepositions, and adjectives and adverbs, you’re going to get most of the questions right. And if an error involving one of those concepts doesn’t appear, there’s a very good chance that there’s no error at all. Thinking like that is a lot more effective than worrying about why it’s just as correct to say “though interesting, the lecture was also very long” as it is to say, “though it was interesting, the lecture was also very long.”

I’m not denying that understanding why both forms are correct is interesting or ultimately useful. I’m simply saying that if you have a limited amount of time and energy, you’re better served by zeroing in on what you really need to know.