by Erica L. Meltzer | Jan 20, 2016 | Blog, The New SAT

Update #2 (1/27/16): Based on the LinkedIn job notification I received yesterday, it seems that ETS will be responsible for overseeing essay grading on the new SAT. That’s actually a move away from Pearson, which has been grading the essays since 2005. Not sure what to think of this. Maybe that’s the bone the College Board threw to ETS to compensate for having taken the actual test-writing away. Or maybe they’re just trying to distance themselves from Pearson.

Update: Hardly had I published this post when I discovered recent information indicating that ETS is still playing a consulting role, along with other organizations/individuals, in the creation of the new SAT. I hope to clarify in further posts. Even so, the information below raises a number of significant questions.

Original post:

Thanks to Akil Bello over at Bell Curves for finally getting an answer:

(In case the image is too small for you to read, the College Board’s Aaron Lemon-Strauss states that “with rSAT we manage all writing/form construction in-house. use some contractors for scale, but it’s all managed here now.” You can also view the original Twitter conversation here.)

Now, some questions:

What is the nature of the College Board’s contract with ETS?

Who exactly is writing the actual test questions?

Who are these contractors “used for scale,” and what are their qualifications? What percentage counts as “some?”

What effect will this have on the validity of the redesigned exam? (As I learned from Stanford’s Jim Milgram, one of the original Common Core validation committee members, many of the College Board’s most experienced psychometricians have been replaced.)

Are the education officials who are mandated the redesigned SAT in Connecticut, Michigan, Colorado, Illinois, and New York City aware that the test is no longer being written by ETS?

Why has this not been reported in the media? I cannot recall a single article, in any outlet, about the rollout of the new test that even alluded to this issue. ETS has been involved in writing the SAT since the 1940s. It is almost impossible to overstate what a radical change this is.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jan 18, 2016 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

For those of you who haven’t been following the College Board’s recent exploits, the company is in the process of staging a massive, national attempt to recapture market share from the ACT. Traditionally, a number of states, primarily in the Midwest and South, have required the ACT for graduation. Over the past several months, however, several states known for their longstanding relationships with the ACT have abruptly – and unexpectedly – announced that they will be dropping the ACT and mandating the redesigned SAT. The following commentary was sent to me by a West Coast educator who has been closely following these developments.

For What It’s Worth

On December 4, 2015 a 15-member evaluation committee met in Denver, Colorado to begin the process of awarding a 5-year state testing contract to either the ACT, Inc. or the College Board. After meeting three more times (December 10, 11, and 18th) the evaluation committee awarded the Colorado contract to the College Board on December 21, 2015. The committee’s meetings were not open to the public and the names of the committee members were not known until about two weeks later.

Once the committee’s decision became public, parents complained that it placed an unfair burden on juniors who had been preparing for the ACT. Over 150 school officials responded by sending a protest letter to Interim Education Commissioner Elliott Asp. The letter emphasized the problem faced by juniors and also noted that Colorado would be abandoning a test for which they had 15 years of data for a new test with no data. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jan 17, 2016 | Blog, The New SAT

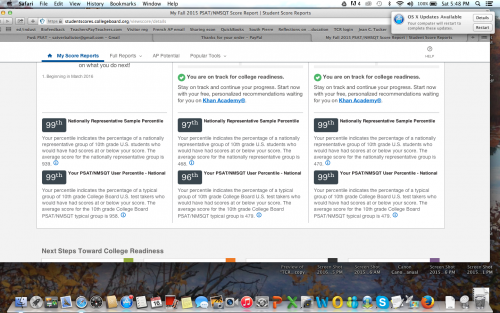

A couple of posts back, I wrote about a recent Washington Post article in which a tutor named Ned Johnson pointed out that the College Board might be giving students an exaggeratedly rosy picture of their performance on the PSAT by creating two score percentiles: a “user” percentile based on the group of students who actually took the test; and a “national percentile” based on how the student would rank if every 11th (or 10th) grader in the United States took the test — a percentile almost guaranteed to be higher than the national percentile.

When I read Johnson’s analysis, I assumed that both percentiles would be listed on the score report. But actually, there’s an additional layer of distortion not mentioned in the article.

I stumbled on it quite by accident. I’d seen a PDF-form PSAT score report, and although I only recalled seeing one set of percentiles listed, I assumed that the other set must be on the report somewhere and that I simply hadn’t noticed them.

A few days ago, however, a longtime reader of this blog was kind enough to offer me access to her son’s PSAT so that I could see the actual test. Since it hasn’t been released in booklet form, the easiest way to give me access was simply to let me log in to her son’s account (it’s amazing what strangers trust me with!).

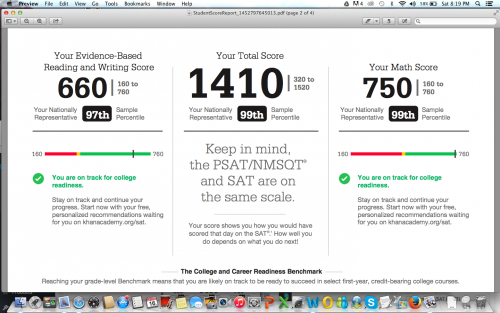

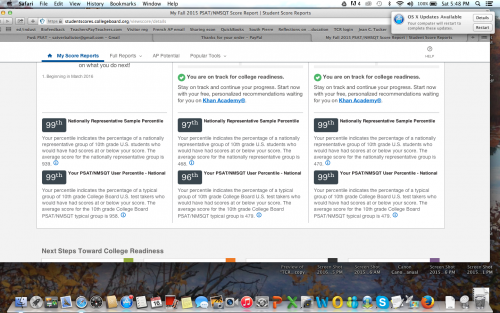

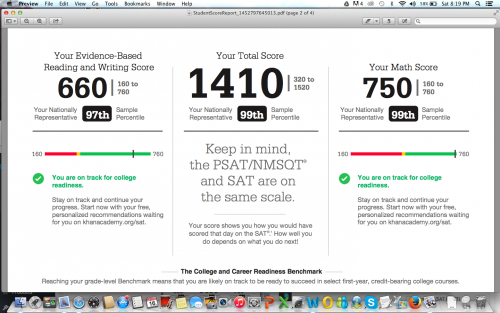

When I logged in, I did in fact see the two sets of percentiles, with the national, higher percentile of course listed first. But then I noticed the “download report” button, and something occurred to me. The earlier PDF report I’d seen absolutely did not present the two sets of percentiles as clearly as the online report did — of that I was positive.

So I downloaded a report, and sure enough, only the national percentiles were listed. The user percentile — the ranking based on the group students who actually took the test — was completely absent. I looked over every inch of that report, as well as the earlier report I’d seen, and I could not find the user percentile anywhere.

Unfortunately (well, fortunately for him, unfortunately for me), the student in question had scored extremely well, so the discrepancy between the two percentiles was barely noticeable. For a student with a score 200 points lower, the gap would be more pronounced. Nevertheless, I’m posting the two images here (with permission) to illustrate the difference in how the percentiles are reported on the different reports.

Somehow I didn’t think the College Board would be quite so brazen in its attempt to mislead students, but apparently I underestimated how dirty they’re willing to play. Giving two percentiles is one thing, but omitting the lower one entirely from the report format that most people will actually pay attention to is really a new low.

I’ve been hearing tutors comment that they’ve never seen so many students obtain reading scores in the 99th percentile, which apparently extends all the way down to 680/760 for the national percentile, and 700/760 for the user percentile. Well…that’s what happens when a curve is designed to inflate scores. But hey, if it makes students and their parents happy, and boosts market share, that’s all that counts, right? Shareholders must be appeased.

Incidentally, the “college readiness” benchmark for 11th grade reading is now set at 390. 390. In contrast, the I confess: I tried to figure out what that corresponds to on the old test, but looking at the concordance chart gave me such a headache that I gave up. (If anyone wants to explain it me, you’re welcome to do so.) At any rate, it’s still shockingly low — the benchmark on the old test was 550 — as well as a whopping 110 points lower than the math benchmark. There’s also an “approaching readiness” category, which further extends the wiggle room.

A few months back, before any of this had been released, I wrote that the College Board would create a curve to support the desired narrative. If the primary goal was to pave the way for a further set of reforms, then scores would fall; if the primary goal was to recapture market share, then scores would rise. I guess it’s clear now which way they decided to go.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jan 10, 2016 | Blog, The New SAT

Apparently I’m not the only one who thinks the College Board might be trying to pull some sort of sleight-of-hand with scores for the new test.

In this Washington Post article about the (extremely delayed) release of 2015 PSAT scores, Ned Johnson of PrepMatters writes:

Here’s the most interesting point: College Board seems to be inflating the percentiles. Perhaps not technically changing the percentiles but effectively presenting a rosier picture by an interesting change to score reports. From the College Board website, there is this explanation about percentiles:

Percentiles

A percentile is a number between 0 and 100 that shows how you rank compared to other students. It represents the percentage of students in a particular grade whose scores fall at or below your score. For example, a 10th-grade student whose math percentile is 57 scored higher or equal to 57 percent of 10th-graders.

You’ll see two percentiles:

The Nationally Representative Sample percentile shows how your score compares to the scores of all U.S. students in a particular grade, including those who don’t typically take the test.

The User Percentile — Nation shows how your score compares to the scores of only some U.S. students in a particular grade, a group limited to students who typically take the test.

What does that mean? Nationally Representative Sample percentile is how you would stack up if every student took the test. So, your score is likely to be higher on the scale of Nationally Representative Sample percentile than actual User Percentile.

On the PSAT score reports, College Board uses the (seemingly inflated) Nationally Representative score, which, again, bakes in scores of students who DID NOT ACTUALLY TAKE THE TEST but, had they been included, would have presumably scored lower. The old PSAT gave percentiles of only the students who actually took the test.

For example, I just got a score from a junior; 1250 is reported 94th percentile as Nationally Representative Sample percentile. Using the College Board concordance table, her 1250 would be a selection index of 181 or 182 on last year’s PSAT. In 2014, a selection index of 182 was 89th percentile. In 2013, it was 88th percentile. It sure looks to me that College Board is trying to flatter students. Why might that be? They like them? Worried about their feeling good about the test? Maybe. Might it be a clever statistical sleight of hand to make taking the SAT seem like a better idea than taking the ACT? Nah, that’d be going too far.

I’m assuming that last sentence is intended to be taken ironically.

One quibble. Later in the article, Johnson also writes that “If the PSAT percentiles are in fact “enhanced,” they may not be perfect predictors of SAT success, so take a practice SAT.” But if PSAT percentiles are “enhanced,” who is to say that SAT percentiles won’t be “enhanced” as well?

Based on the revisions to the AP exams, the College Board’s formula seems to go something like this:

(1) take a well-constructed, reasonably valid test, one for which years of data collection exists, and declare that it is no longer relevant to the needs of 21st century students.

(2) Replace existing test with a more “holistic,” seemingly more rigorous exam, for which the vast majority of students will be inadequately prepared.

(3) Create a curve for the new exam that artificially inflates scores.

(4) Proclaim students “college ready” when they may be still lacking fundamental skills.

(5) Find another exam, and repeat the process.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 29, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT

Among the partial truths disseminated by the College Board, the phrase “guessing penalty” ranks way up there on the list of things that irk me most. In fact, I’d say it’s probably #2, after the whole “obscure vocabulary” thing.

Actually, calling it a partial truth is generous. It’s actually more of a distortion, an obfuscation, a misnomer, or, to use a “relevant” word, a lie.

Let’s deconstruct it a bit, shall we?

It is of course true that the current SAT subtracts an additional ¼ point for each incorrect answer. While this state of affairs is a perennial irritant to test-takers, not to mention a contributing factor to the test’s reputation for “trickiness,” it nevertheless serves a very important purpose – namely, it functions as a corrective to prevent students from earning too many points from lucky guessing and thus from achieving scores that seriously misrepresent what they actually know. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 27, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT

In a Washington Post article describing the College Board’s attempt to capture market share back from the ACT, Nick Anderson writes:

Wider access to markets where the SAT now has a minimal presence would heighten the impact of the revisions to the test that aim to make it more accessible. The new version [of the SAT], debuting on March 5, will eliminate penalties for guessing, make its essay component optional and jettison much of the fancy vocabulary, known as “SAT words,” that led generations of students to prepare for test day with piles of flash cards.

Nick Anderson might be surprised to discover that “jettison” is precisely the sort of “fancy” word that the SAT tests.

But then again, that would require him to do research, and no education journalist would bother to do any of that when it comes to the SAT. Because, like, everyone just knows that the SAT only tests words that no one actually uses. (more…)