by Erica L. Meltzer | Jul 5, 2016 | Blog, Issues in Education

A couple of days ago, I came across this article from Boston WBUR, courtesy of Diane Ravitch’s blog. It tells the story of David Weinstein, who has taught first grade at the Pierce School in Brookline, MA, for 29 years but is retiring because he can no longer tolerate being a data-collector for six year-olds.

As Weinstein explains:

[Retirement is] something I’ve been thinking about for a long time now, just in terms of how the profession has changed and what we’re asking of kids. It’s a much more pressure-packed kind of job than it used to be. And it’s challenging. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jun 1, 2016 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

In the spring of 2015, when the College Board was field testing questions for rSAT, a student made an offhand remark to me that didn’t seem like much at the time but that stuck in my mind. She was a new student who had already taken the SAT twice, and somehow the topic of the Experimental section came up. She’d gotten a Reading section, rSAT-style.

“Omigod,” she said. “It was, like, the hardest thing ever. They had all these questions that asked you for evidence. It was just like the state test. It was horrible.”

My student lived in New Jersey, so the state test she was referring to was the PARCC.

Even then, I had a pretty good inkling of where the College Board was going with the new test, but the significance of her comment didn’t really hit me until a couple of months ago, when states suddenly starting switching from ACT to the SAT. I was poking around the internet, trying to find out more about Colorado’s abrupt and surprising decision to drop the ACT after 15 years, and I came across a couple of sources reporting that not only would rSAT replace the ACT, but it would replace PARCC as well. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Mar 3, 2016 | Blog, SAT Reading

1) Start with your favorite passage(s)

You’re going to be sitting and reading for over an hour (well over an hour, if you count the Writing section), so you don’t want to blow all your energy on the first couple of passages. Take a few minutes at the start of the test, and see which passages seem easiest/most interesting, and which ones seem hardest/least interesting. Start with the easy ones, and end with the hard ones. This is not the ACT; you have plenty of time, and taking a few minutes to do this step can help you pace yourself more efficiently. You’ll get a confidence boost upfront, and you’ll be less likely to panic when you hit the harder stuff later on.

2) Be willing to skip questions

Unless you’re absolutely set on getting an 800 or close to it, you don’t need to answer every question — in fact, you probably shouldn’t (although you should always make sure to fill in answer for every question, since the quarter point wrong-answer penalty has been eliminated). If your first reaction when you look at a question is that you have no idea what it’s asking, that’s probably a sign you’re better off moving onto other things. That is particularly true on the Reading section because questions are not presented in order of difficulty. A challenging question can be followed by a very easy one, and there’s no sense getting hung up on the former if you can answer the latter quickly. And if you truly hate graph questions or Passage 1/Passage 2 relationship questions, for example, then by all means just skip them and be done with it.

3) Be willing to skip an entire passage

This might sound a little radical, but hear me out. It’s an adaptation of an ACT strategy that actually has the potential to work even better on the new SAT than it does on the ACT. This is especially true if you consistently do well on the Writing section; a strong score there can compensate if you are weaker in Reading, giving you a respectable overall Verbal score. Obviously this is not a good strategy if you are aiming for a score in the 700s; however, if you’re a slow but solid reader who is scoring in the high 500s and aiming for 600s, you might want to consider it.

Think of it this way: if four of the passages are pretty manageable for you but the fifth is very hard, or if you feel a little short on time trying to get through every passage and every question, this strategy allows you to focus on a smaller number of questions that you are more likely to answer correctly. In addition, you should pick one letter and fill it in for every question on the set you skip. Assuming that letters are distributed evenly as correct answers (that is, A, B, C, and D are correct approximately the same number of times on a given test, and in a given passage/question set), you will almost certainly grab an additional two or even three points.

If you’re not a strong reader, I highly recommend skipping either the Passage 1/Passage 2, or any fiction passages that include more antiquated language, since those are the passage types most likely to cause trouble.

4) Label the “supporting evidence” pairs before you start the questions

Although you may not always want to use the “plug in” strategy (plugging in the line references from the second question into the first question in order to answer both questions simultaneously), it’s nice to have the option of doing so. If you don’t know the “supporting evidence” question is coming, however, you can’t plug anything in. And if you don’t label the questions before you start, you might not remember to look ahead. This is particularly true when the first question is at the bottom of one page and the second question is at the top of the following page.

5) Don’t spend too much time reading the passages

You will never — never — remember every single bit of a passage after a single read-through, so there’s no point in trying to get every last detail. The most important thing is to avoid getting stuck in a reading “loop,” in which you re-read a confusing phrase or section of a passage multiple times, emerging with no clearer a sense of what it’s saying than when you began. This is a particular danger on historical documents passages, which are more likely to include confusing turns of phrase. Whatever you do, don’t fall into that trap! You will waste both time and energy, two things you cannot afford to squander upfront. Gently but firmly, force yourself to move on, focusing on the beginning and the end for the big picture. You can worry about the details when you go back.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 6, 2015 | Blog, Issues in Education, The New SAT

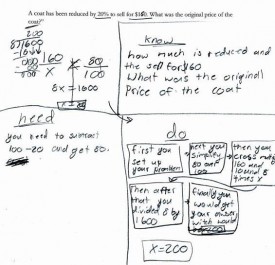

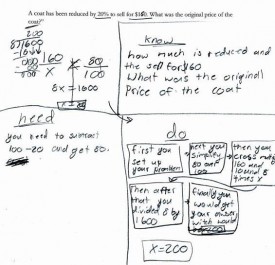

I’m not sure how I missed it when it came out, but Barry Garelick and Katherine Beals’s “Explaining Your Math: Unnecessary at Best, Encumbering at Worst,” which appeared in The Atlantic last month, is a must-read for anyone who wants to understand just how problematic some of Common Core’s assumptions about learning are, particularly as they pertain to requiring young children to explain their reasoning in writing.

(Side note: I’m not sure what’s up with the Atlantic, but they’ve at least partially redeemed themselves for the very, very factually questionable piece they recently ran about the redesigned SAT. Maybe the editors have realized how much everyone hates Common Core by this point and thought it would be in their best interest to jump on the bandwagon, but don’t think that the general public has yet drawn the connection between CC and the Coleman-run College Board?)

I’ve read some of Barry’s critiques of Common Core before, and his explanations of “rote understanding” in part provided the framework that helped me understand just what “supporting evidence” questions on the reading section of the new SAT are really about.

Barry and Katherine’s article is worth reading in its entirety, but one point that struck me as particularly salient.

Math learning is a progression from concrete to abstract…Once a particular word problem has been translated into a mathematical representation, the entirety of its mathematically relevant content is condensed onto abstract symbols, freeing working memory and unleashing the power of pure mathematics. That is, information and procedures that have been become automatic frees up working memory. With working memory less burdened, the student can focus on solving the problem at hand. Thus, requiring explanations beyond the mathematics itself distracts and diverts students away from the convenience and power of abstraction. Mandatory demonstrations of “mathematical understanding,” in other words, can impede the “doing” of actual mathematics.

Although it’s not an exact analogy, many of these points have verbal counterparts. Reading is also a progression from concrete to abstract: first, students learn that letters are represented as abstract symbols, and that those symbols correspond to specific sounds, which get combined in various ways. When students have mastered the symbol/sound relationship (decoding) and encoded them in their brains, their working memories are freed up to focus on the content of what they are reading, a switch that normally occurs around third or fourth grade.

Amazingly, Common Core does not prescribe that students compose paragraphs (or flow charts) demonstrating, for example, that they understand why c-a-t spells cat. (Actually, anyone, if you have heard of such an exercise, please let me know. I just made that up, but given some of the stories I’ve heard about what goes on in classrooms these days, I wouldn’t be surprised if someone, somewhere were actually doing that.)

What CC does, however, is a slightly higher level equivalent — namely, requiring the continual citing of textual “evidence.” As I outlined in my last couple of posts, CC, and thus the new SAT, often employs a very particular definition of “evidence.” Rather than use quotations, etc. to support their own ideas about a work or the arguments it contains (arguments that would necessarily reveal background knowledge and comprehension, or lack thereof), students are required to demonstrate their comprehension over and over again by “staying within the four corners of the text,” repeatedly returning it to cite key words and phrases that reveal its meaning — in other words, their understanding of the (presumably) self-evident principle that a text means what it means because it says what it says. As is true for math, entire approach to reading confuses demonstration of a skill with “deep” possession of that skill.

That, of course, has absolutely nothing to do with how reading works in the real world. Nobody, nobody, reads this way. Strong readers do not need to stop repeatedly in order to demonstrate that they understand what they’re reading. They do not need to point to words or phrases and announce that they mean what they mean because they mean it. Rather, they indicate their comprehension by discussing (or writing about) the content of the text, by engaging with its ideas, by questioning them, by showing how they draw on or influence the ideas of others, by pointing out subtleties other readers might miss… the list goes on and on.

Incidentally, I’ve had adults gush to me that their children/students are suddenly acquiring all sorts of higher level skills, like citing texts and using evidence, but I wonder whether they’re actually being taken in by appearances. As I mentioned in my last post, although it may seem that children being taught this way are performing a sophisticated skill (“rote understanding”), they are actually performing a very basic one. I think Barry puts it perfectly when he says that It is as if the purveyors of these practices are saying: “If we can just get them to do things that look like what we imagine a mathematician does, then they will be real mathematicians.”

In that context, these parents’/teachers’ reactions are entirely understandable: the logic of what is actually going on is so bizarre and runs so completely counter to a commonsense understanding of how the world works that such an explanation would occur to virtually no one who hadn’t spent considerable time mucking around in the CC dirt.

To get back to the my original point, though, the obsessive focus on the text itself, while certainly appropriate in some situations, ultimately serves to prohibit students from moving beyond the text, from engaging with its ideas in any substantive way. But then, I suspect that this limited, artificial type of analysis is actually the goal.

I think that what it ultimately comes down to is assessment — or rather the potential for electronic assessment. Students’ own arguments are messier, less “objective,” and more complicated, and thus more expensive, to assess. Holistic, open-ended assessment just isn’t scalable the same way that computerized multiple choice tests are, and choosing/highlighting specific lines of a text is an act that lends itself well to (cheap, automated) electronic grading. And without these convenient types of assessments, how could the education market ever truly be brought to scale?

by Erica L. Meltzer | May 31, 2011 | Blog, General Tips

For some reason, every time I offer this little pearl of wisdom to a student, I’m inevitably greeted with looks that range from dubious to downright offended.

I can almost hear the person think, “But that’s what I did in first grade. Putting your finger on the page is for little kids. Doesn’t Erica get that I’m taking this test to get into college? I thought she was smarter than that. Besides, everyone will think that I look stupid!”

Guess what: not a single other test-taker in the room with you cares in the least whether you put your finger on the page or not. Everyone will be so focused on their own work that they won’t have space in their brains to worry about what you’re doing.

According to speed-reading expert Abby Marks Beale,

Because the eyes naturally follow movement, placing a finger, hand or card on a page and strategically moving it down the text, a reader will keep naturally keep their place, be more focused and read faster. This helps readers concentrate and understand what they read making reading a more satisfying experience.

While I’m not sure that most people are seeking”a satisfying reading experience” on the SAT or the ACT, they certainly are looking for increased speed and improved concentration.

This is not just about reading passages, by the way — it helps on every part of the exam. On SAT Writing/ACT English, for example, your eye has a way of filling in the correct answer without your even realizing it (this is particularly true for adjective vs. adverb questions). Unless you look really, really closely, you often simply won’t “see” the error, regardless of how well you understand what’s being tested. And on Math, it’s so easy to forget to solve for 2x and accidentally solve for x instead… Putting your finger on the page may seem like a small thing, but if it saves you from overlooking key parts