Catherine Johnson’s recent post over at Kitchen Table Math got me thinking about a relationship that’s I’ve been curious about for a while: namely, that between exposure to phonics and the ability to figure use roots to figure out unfamiliar words on the SAT.

One of the things I’ve begun to notice recently is that I can generally distinguish between kids who were taught to read using a whole language approach and those taught to read using phonics. Almost invariably, the kids who were taught using whole language have considerably more difficult breaking words apart and examining their component parts. I tend to see this much more prominently when I tutor French or Italian — often a student will read the first couple of letters in a word and then simply guess what the rest of it says, which is an absolute disaster in French — but I see it when I tutor the SAT as well, albeit in a more roundabout way.

For example, one Blue Book sentence completion contains the the answer choice “deferential,” which is a word that most of my students are unfamiliar with. What’s interesting, though, is how they react to it. Usually I ask them if they can relate it to a word they know, and typically they can’t think of anything, but recently one of my students said that it looked like “different.” That one threw me a little. On one hand, my student was absolutely right: “defer” and “differ” do sound similar. Unfortunately, they have nothing to do with one another. And that, in turn, made me wonder about the whole idea of asking students to relate unfamiliar words to words they already know. The underlying assumption of that strategy is that students already know what parts of words they should and should not focus on, that they can distinguish between “sounds similar” and “related in meaning.” And that assumption, as I’ve discovered, is not necessarily a valid one.

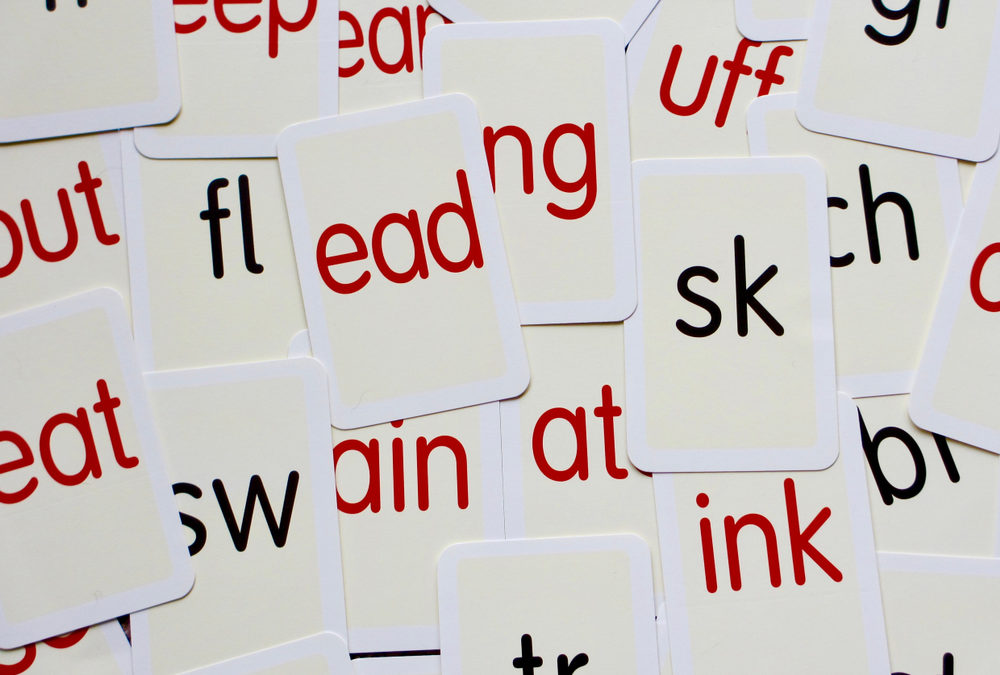

I realize that this isn’t directly related to the phonics issue, but it did get me thinking about how some students approach language in general. If you’re taught to look at words as complete entities rather than composites of individual parts (preflxes, roots, suffixes), each of which makes a distinct sound, then of course you won’t know what constitutes a real (etymological) relationship between two words you’ve never seen. And if you’re encouraged to think that way in first grade and then work that way for the next ten or so years, you’re going to have a very difficult time sounding out words by the time you hit 16.

(As a side note, I think foreign language classes squander an unbelievable opportunity to introduce whole-language students to phonetics. I do my best to make my foreign-language students sound out unfamiliar words in French and Italian, and they hate it, but sometimes, once they understand that knowing exactly what a word says makes it so much easier to follow a sentence or paragraph or article, they start to see the usefulness behind it.)