by Erica L. Meltzer | Jun 23, 2020 | Phonics, Reading Wars, The Science of Reading

One of the most serious, and most persistent, misconceptions in the world of reading early reading instruction involves the use of context clues. Regardless of whether they are explicitly taught an incorrect interpretation of three/multi-cueing system or simply absorb its tenets in graduate school or via professional development, many teachers of beginning readers erroneously learn that children should focus primarily on beginning/ending letters and then use a variety of guess-and-check methods (e.g., picture clues, other information in the text) to make educated guesses about unfamiliar words.

If you’re not familiar with the research, a reliance on context clues has been identified as a compensatory strategy for weak decoding skills (Nicholson, 1992; Stanovich, 1986); as children become more proficient decoders, they spend less time looking at contextual information.

Louise Spear-Swerling, professor of Special Education at Southern Connecticut State University, sums the findings up as follows:

Skilled readers do not need to rely on pictures or sentence context in word identification, because they can read most words automatically, and they have the phonics skills to decode occasional unknown words rapidly. Rather, it is the unskilled readers who tend to be dependent on context to compensate for poor word identification. Furthermore, many struggling readers are disposed to guess at words rather than to look carefully at them, a tendency that may be reinforced by frequent encouragement to use context.

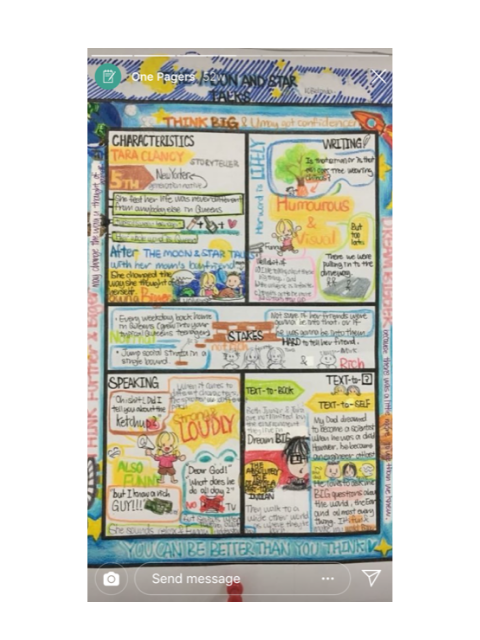

In her 1998 article on the misinterpretation of the three-cueing system, Marilyn Jäger Adams furthermore makes the point that while skilled readers do in fact make use a combination of orthographic, syntactic, and semantic clues, they do so in order to construct meaning rather than to literally decode words. The misinterpretation of the graphic that has filtered down into many elementary-school classrooms is based on a confusion between “reading as extracting meaning from text” (which presumes solid decoding) and “reading as turning squiggles on a page into words.”

To be clear, using a combination of first letters and pictures, or other parts of a text, and making educated guesses based on “what would make sense” may indeed result in beginning readers coming up with correct words, or a generally accurate understanding of a particular scenario. But that’s beside the point.

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Thinking

To have a serious discussion about what types of strategies should be taught, and when, and why, it is necessary to distinguish between short-term and long-term thinking.

In short-term thinking, the focus is on getting the child to understand the particular text in front of them, at that particular moment. Exactly how that happens is not overly important.

And after all, the purpose of reading is to understand the text (or, to put it in edu-parlance to “construct meaning”). Obviously.

Understandably, this is a very appealing viewpoint, and one that seems to make intuitive sense: learning to read can be very challenging for certain children, and if especially one is working with a slow, struggling reader, the impulse to have them glean whatever they can, however they can, is entirely understandable. Any tools they can use to figure out what’s going on are helpful, right?

In the long term… No, actually.

The problem is that the (cueing) strategies that allow a beginning reader to get the gist of simple pictures books fall very, very far short when applied to the far more challenging texts students will be expected to read only a few years later. A kindergartner or first-grader who appears to be basically on track may in fact be missing very fundamental key skills.

Moreover, the habit of guessing at unfamiliar words is not one that children naturally outgrow—once established, it is often extraordinarily difficult to break.

Combine that with persistent decoding issues, and you end up with a burgeoning middle-schooler who’s just old enough to really push back when someone tries to intervene but not quite mature enough to appreciate why it’s so important for her to learn to sound out multisyllabic words phonetically (as Richard McManus will currently attest).

All that said, the use of context clues does in fact have a place in early reading instruction. But the key piece is that context must be used to support phonetic decoding (and thus orthographic mapping), not replace it.

Practically speaking, this involves the decoding of words that are only partly phonetic, or whose exact pronunciation cannot be determined from the way they are written.

As Tunmer (1990; see pp. 112-113) has explained, phonetic knowledge and the ability to use context combine to create a positive feedback loop in which context is used to actually strengthen phonetic understanding and facilitate orthographic mapping—the process by which words get stored in the brain as sound-syllable correspondences and made available for automatic retrieval.

Essentially, when children with a solid phonetic understanding of the English code encounter irregularly spelled/pronounced words, they may use context clues to bootstrap themselves into an understanding of how those words are pronounced. That reinforces an understanding of more complex phonetic patterns and allows challenging language to be read more easily in the future.

Some children may figure this out their own, but there is no reason that others cannot be taught this strategy explicitly.

This phenomenon also supports the finding that children with good decoding skills can often infer the pronunciations of moderately irregularly word (Groff, 1987), something that directly contradicts the notion that English is too irregular for phonetic knowledge to be effective.

What the Heck is a MOSS-kwih-toe?

I’m going to illustrate this with a personal anecdote involving one of my earliest reading-related memories.

It happened when I was in first grade, and it involved the word mosquito.

Although this word is spelled in a way that is not entirely unrelated to its pronunciation, there are a couple of notable irregularities.

- First, the “qu” makes a “k” sound, as opposed to its usual “kw” sound.

- Second, there’s no obvious information about which syllable should be stressed.

So when I encountered this word in print at the age of six, I initially read it as MOSS-kwih-toe.

“Huh?” I remember thinking. “What the heck is a MOSSkwitoe?”

I knew that didn’t make sense, and I knew I wasn’t reading the word correctly, but I couldn’t fathom what it might actually be.

So I kept on plugging along, and a couple of minutes later, I suddenly had a lightbulb moment.

“Oh!” I thought. “Of course. The word is pronounced muskeetoe!”

I was really quite astonished to have figured it out. I had a huge vocabulary but was by no means an exceptional decoder. You know those kids who teach themselves to read at three? Well, I wasn’t one of them. I wasn’t even in the top reading group! But the incident made such an extraordinary impression on me that I still remember my thought process with almost total clarity more than 30 years later.

So let’s review what I did:

1) I used the specific sequence of letters and my knowledge of the sounds they made to take me as far as I could possibly go toward identifying the word.

2) Once I realized the story involved some sort of insect that flew and buzzed around during the summer, I drew the logical conclusion about the word’s pronunciation.

3) I got a lesson in the fact the “qu” can make a “k” sound in certain circumstances—an alternate phonetic pattern that helped me identify other challenging words quickly in the future (and eventually facilitated my ability to grasp French pronunciation).

4) The sound-spelling correspondence of the whole word was from then on etched into my mind in metaphorical granite (i.e., orthographically mapped).

5) I learned that even if words weren’t straightforwardly phonetic, I could combine my sound-spelling knowledge with my other skills and figure things out. That was an immensely powerful realization.

The interesting part is that technically speaking, my process was a stellar example of the three-cueing model. It involved the construction of (literal) meaning using the interplay among clues based on orthography (sequence of letters), syntax (the word had to be a noun based on its position in the sentence), and semantics (the story must have involved a tiny, buzzing insect).

The key piece, however, is that my close attention to sound-spelling correspondences underlay my ability to engage the other systems effectively. I did not look at the first letter(s) and make a semi-random guess based on context (the way I later saw many of my own, much older students do). If I had, in the absence of any solid contextual information at that point, I might have come up with something like mouse.

Rather, I paid close attention to all the letters in the word—beginning, middle, and end—in an attempt to sound it out, and only when that wasn’t enough did I move to thinking about the larger context of the story to in order to make the leap from that baffling collection of letters to certainty about a real word.

That leads me to my next point, namely that the episode was also consistent with the finding that children who learn to read phonetically are able to produce nonsense words/pronunciations—something that children who are taught via whole language do not do (Barr, 1974-5; click here for a discussion of the findings). Had I jumped to plug in a word I already knew how to read, I would have missed out on a significant learning opportunity. And even if I had managed to correctly guess mosquito, I would have missed out on an important phonetic lesson and would not have been able to carry that new knowledge forward into other words.

As Ehri points out, children who exhibit this type of phonetic non-word decoding in first grade move more quickly into the full alphabetic phase, in which “beginners become able to form connections between all of the graphemes in spellings and the phonemes in pronunciations to remember how to read words.” Indeed, by second grade, I was basically a totally fluent reader. Once things clicked, I never looked back.

About the Three-Cueing System…

Let me conclude by saying that writing (and re-writing) this piece has actually been a rather enlightening process for me, not least because it allowed me to revisit a memorable childhood experience from an adult perspective and—entirely to my surprise—be able to analyze it in light of theories with which I’ve become acquainted only relatively recently. When I first began to write about the episode, I was unaware of just how clearly it embodied key findings about how children learn to read; it was only as I began to really probe it that I realized how illustrative it actually was.

It also made me develop a more nuanced understanding of the three-cueing system, as well as a better understanding of how things went so badly awry. What I’ve described here certainly isn’t the “look at the first letter and the picture and think about what would make sense” approach, but it also isn’t quite the mature use of textual cues employed by skilled readers to, say, determine correct definitions of multi-meaning words. Instead, it’s somewhere in the middle.

It’s precisely that in-between place that makes things so tricky, and I think it points to the overwhelming importance of precise language when discussing techniques for reading instruction. Indeed, so many conversations about this topic devolve into free-for-alls simply because various parties cannot agree on what central terms mean. (E.g., for researchers, the term “sight word” refers to a word that has been orthographically mapped and can be read instantaneously, whereas for teachers it generally refers to the high-frequency words on the Dolch/Fry lists that beginning readers are expected to memorize more or less by rote.)

It’s very easy to imagine how a cautious assertion like, “In some instances, children can use context clues to help them identify unknown words” could get transformed into, “Let’s look at the first letter and the picture and ask ourselves what the word might be.” Those two statements might not seem terribly different on the surface, but in fact they’re worlds apart.

The cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham has warned that inconclusive (or, I would add, poorly understood) theoretical models can easily get translated into ineffective classrooms practices, and I think the three-cueing system is the poster child for that. It’s not enough to say, for example, that skilled reading involves a complex interplay of systems; inevitably, given the history of reading instruction in the United States, that will be used to promote harmful ideas about the unimportance of phonetic decoding. When the devil is in the details, every word counts.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jun 6, 2020 | Books

If you’re looking to publish a test-prep or subject-specific study guide, or if you just have a great idea for a general education-related book, The Critical Reader may be able to bring your work to market.

We’re looking to expand our book offerings and are currently seeking manuscript submissions in the humanities and social sciences, with particular interest in the following areas:

- AP® Exams, especially Human Geography, Government and Politics, Psychology, Spanish Language and Culture, and World History

- English as a Second Language, including TOEFL® and IELTS® preparation

- SHSAT

- SSAT®/ISEE®

- Phonics-based reading instruction

Other subjects will also be considered, though, so this should not be treated as an exhaustive list.

As an established player within our market, we are able to offer a traditional publishing model: you don’t pay us—we pay you. We can also offer support throughout the publication process, including editing, formatting, and cover design.

Please click here for submission guidelines.

by Erica L. Meltzer | May 24, 2020 | Blog, College Admissions

So it’s official: The University of California—the country’s largest public university system, serving several hundred thousand students—has voted to phase out standardized testing.

The SAT and ACT will be optional for freshman applicants for applicants in 2021 and 2022; for 2023-4, test scores will be used only for out-of-state-students and to determine scholarship awards; and will be eliminated completely in 2025. If a new, UC-created exam is not ready by that point, then no exam will be considered.

This is obviously a major shakeup in the testing industry, although not a completely unforeseen one. Historically, there has been tension between the University of California and the College Board, with discussions of abandoning the SAT dating back to the early 1990s. More recently, there has been considerable speculation about whether the UCs would continue to require the SAT or ACT essay. Since last winter, however, additional pushback against the use of standardized testing has ramped up. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | May 16, 2020 | ACT Reading, SAT Reading, SAT vs. ACT

I was recently invited to do an interview about SAT vs. ACT Reading on the “Tests and the Rest” podcast, which is run by test-prep experts Amy Seeley and Mike Bergin and covers a wide range of issues related to standardized testing and college admissions. (This is actually the second time they’ve had me on; my previous interview, in which I discussed SAT vs. ACT grammar, can be found here. I’m not sure when the new interview will air but will post something when it does.)

I had a great time chatting with Amy and Mike, and as I looked at my notes, the thought popped into my mind that in all my years of running this blog, I had somehow neglected to devote a post to that particular topic. It also occurred to me that perhaps I’d actually done such a post and simply forgotten about, but when I went back and checked, it turned out that I had in fact never devoted an entire post to that particular topic. So I’m putting it up now. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Apr 25, 2020 | AP

Update, 4/29:

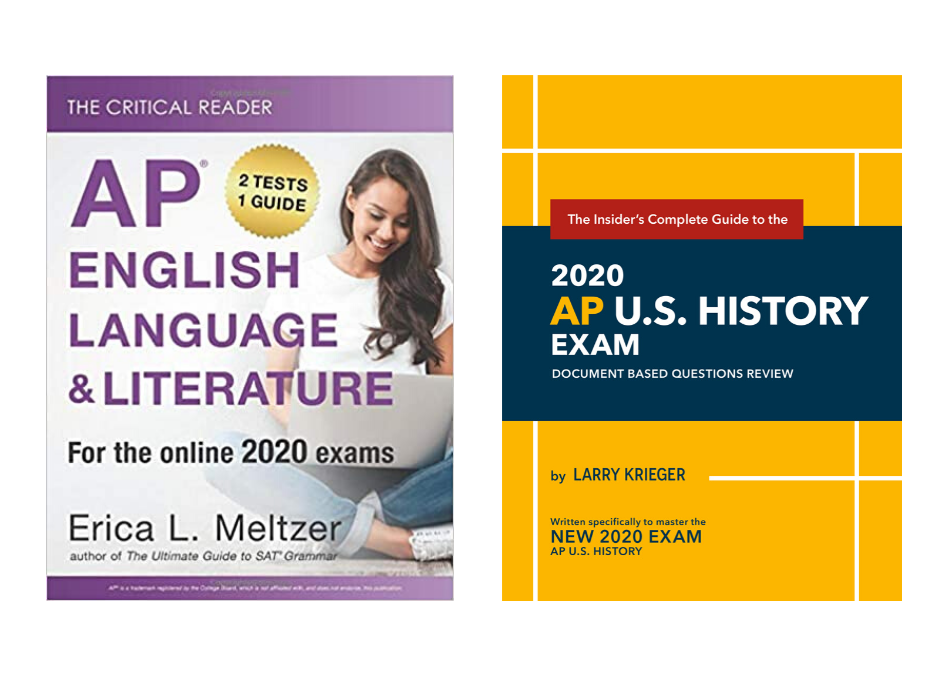

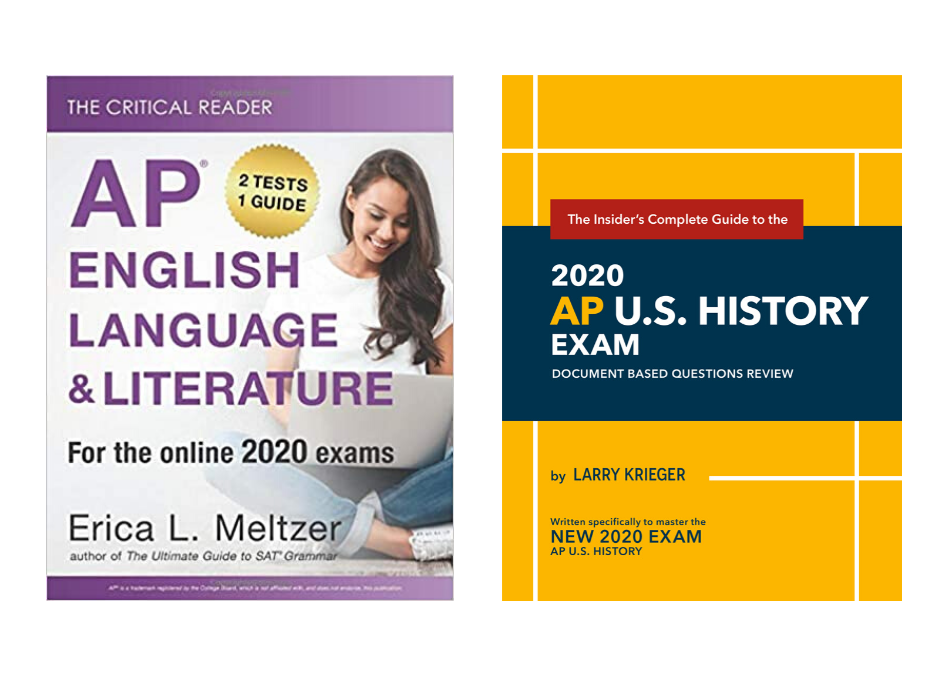

The electronic version of my AP® English Language and Literature guide is now available on Amazon.

Update:

My and Larry Krieger’s mini-guides for the condensed 2020 online AP tests are now available!

Because of a technical issue that resulted in the print version of Larry’s book being delayed on Amazon by nearly a week, Larry asked me to post the entire book as a free PDF download on this site. Click here to access it (do not add to cart; scroll down and click on the link in the description).

If you would like to order a print copy, the book is now available on Amazon as well.

Unfortunately, Larry realized that he would not have enough to time to complete the AP Psychology guide and decided to let that project go.

For logistical reasons, I decided to combine the English Language and English Literature sections into a single print book which, as of 4/25, is available only on Amazon.

I’m currently in the process of trying to get the manuscript formatted so I can make the book available in electronic form. I’m hoping that will happen by mid-week.

I’m also currently trying to determine whether The Critical Reader will be able to stock the book as well, given delayed shipping times.

I’ll post an update as soon as I have more information.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Apr 5, 2020 | AP

In the past few days, the College Board has released important information regarding the 2020 AP exam schedule.

Tests will consist of free-response questions only; last approximately 45 minutes each; and be administered online from May 11-22nd, with additional makeup dates in June.

After some discussion with my SAT vocabulary book co-author and APUSH expert extraordinaire Larry Krieger, I’m happy to announce that we’ve decided to release condensed (approximately 50-page) AP guides that specifically target the 2020 online exams. We’ll aim to make them available within the next 2-3 weeks, sooner if possible.

Our current plan is as follows: I will be covering the AP English Language and Literature exams, and Larry will be handling APUSH. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Mar 29, 2020 | Blog, College Admissions

A couple of weeks ago, as soon as it became clear that there was no way the spring SAT and ACT testing schedule could proceed as normal, I started wondering how the Coronavirus pandemic would affect the trend toward test-optional admissions policies.

No sooner had the thought crossed my mind than an Instagram announcement popped up stating that Case Western had decided to go test-optional for students applying in the fall of 2021. At Case, the policy currently applies to those applicants only; policies for future classes will be determined next winter. Tufts has also announced a similar policy involving a three-year trial period.

From what I understand, it seems likely that the pandemic will consist of multiple, overlapping waves of outbreaks in different regions over a fairly extended period, rather than occurring in one single massive wave, and so it would not be at all surprising if these policies were ultimately extended. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Mar 23, 2020 | Blog

3/24 update: International shipping is not available. I’ve just been notified that Amazon, which prints our books, is not currently shipping orders outside the United States. Because international orders must go through Amazon rather than from our regular warehouse, we unfortunately unable to ship abroad.

As of today (3/23/20), delivery times for *most* Critical Reader books remain unaffected by the novel Coronavirus. Our storage and shipping facility is still open and operating normally, and orders should continue to arrive in approximately 5-7 days.

The only exception is the recently released updated AP English Language and Composition Guide. This item must still be sent from the printer, which is currently experiencing delays. Please allow 10 days for shipping.

We will post an update if there are any changes.

To everyone: please take care and stay safe.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Mar 13, 2020 | Blog, Issues in Education

A number of years ago, an acquaintance enlisted me to help her search Craigslist for a sublet in New York City. This is a daunting task under the best of circumstances, but in this case the difficulty was compounded by the fact that my acquaintance was not a native English speaker—in fact, she did not speak much English at all—nor was she particularly internet savvy.

As someone who had spent a fair amount of time on Craigslist looking for apartments herself, I was well-versed in the various scams that flood the site and adept at the spotting the markers for them: TOO MUCH CAPITALIZATION or too much lower case. Word salad, word soup… Or wording that just somehow seemed “off,” in some vague, undefined way.

My acquaintance, on the other hand, was entirely at sea: she would call the numbers listed and be told that the original rental no longer existed but that she could be shown other, pricier options; or that she would have to hand over exorbitant amounts of money for a deposit, and so on.

I eventually got very frustrated trying to help her. She was oblivious to clear warning signs, and she went running to look at apartment after apartment that just obviously wasn’t going to pan out. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Mar 6, 2020 | Phonics

Attention! This post has moved.

It can now be found at: https://www.breakingthecode.com/10-reasons-three-cueing-system-msv-is-ineffective/

by Erica L. Meltzer | Mar 4, 2020 | Blog

The updated version of The Critical Reader: AP® English Language and Composition Edition is now available.

The guide provides a comprehensive review of all the reading and writing skills tested on the revised 2020 version of the exam. It includes a complete chapter dedicated to each type of multiple-choice reading question; a new multiple-choice writing section; and a section devoted to the three essays, with real student samples and detailed scoring analyses based on the new College Board rubric.

Click here to read a preview.

Please note: The primary changes involve the elimination of vocabulary-based, multiple-answer (I, II, III), and rhetoric questions from the reading section; the addition of a multiple-choice writing section; and a switch from a 9- to a 6-point essay-scoring rubric (essays themselves remain the same).

If you already have the 2018/2019 version of this book, we recommend supplementing it with rhetoric questions from SAT Writing and Language passages, ACT English passages, or the Fixing Paragraphs section of the pre-2016. Click here for examples of real essays scored according to the new rubric.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Feb 29, 2020 | Blog, Issues in Education, Phonics

As I alluded to my previous post, the U. Wisconsin-Madison cognitive psychologist and reading specialist Mark Seidenberg has posted a rebuttal to Lucy Calkins’s manifesto “No One Gets to Own the Term ‘Science of Reading’” on his blog. For anyone interested in understanding the most recent front in the reading wars, I strongly recommend both pieces.

What I’d like to focus on here, however, are the ways in which Calkins’s discussion of phonics reveal a startlingly compromised understanding of the subject for someone of her influence and stature.

In recent years, and largely—as Seidenberg explains—in response to threats to her personal reading-instruction empire, Calkins has insisted that she really believes in the importance of systematic phonics, a claim that comes off as somewhat dubious given the obvious emphasis she places on alternate decoding methods, e.g., covering up letters, using context clues, etc. (Claude Goldenberg, the emeritus Stanford Ed School professor who helped author the recent report on Units of Study, also does a good job of showing how Calkins attempts to play to both sides of the reading debate while clearly holding tight to three-cueing methods.)

That’s obviously a problem, but I think the real question is even more fundamental: not just whether Calkins truly supports the teaching of phonics, but whether she understands what phonics is. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Feb 26, 2020 | Blog, Issues in Education, Phonics

I’ve been so wrapped up in trying to finish my AP English book updates these last few weeks that I somehow missed a new front in the reading wars: Emily Hanford recently published another American Public Media article, this one casting a critical look at Columbia University Teachers College professor Lucy Calkins and her enormously lucrative and influential Units of Study program.

Although Calkins claims to be in favor of phonics (when appropriate, as long as it doesn’t interfere with children’s love of reading), her guides for teachers promote a series of methods that effectively embody the three-cueing system.

The cognitive scientist Mark Seidenberg, a specialist in reading problems who teaches at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, has an excellent blog post in which he methodically dismantles Calkins’s attempts to distance herself from three-cueing methods, and demonstrates the extent to which Calkins engages in semantic game-playing. His reading of Calkins’s work also hints at the depth of her misunderstandings about phonics, some of which are rather astounding. I think they’re very important to highlight, and I’d like to do so in another post. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Feb 23, 2020 | Blog

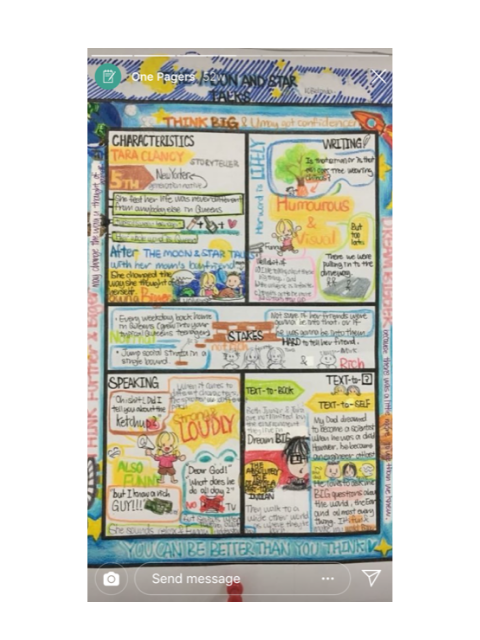

In July of 2015, the math teacher and author of the Truth in American Education blog Barry Garelick wrote an article in which he described the convoluted explanations to simple math problems that students were expected to produce under Common Core, the logic being that the ability to describe one’s mathematical thinking in detail was a sign of “deep understanding.”

As Barry pointed out, however, the process of describing one’s thinking became an end in itself rather a sign of actual comprehension. Essentially, students were being trained to display a set of behaviors that made it appear as if they were thinking deeply, whether or not they truly understood—a phenomenon he termed “rote understanding.”

I still think this is one of the most brilliant phrases I’ve come across in the edu-blogosphere; it perfectly captures the superficial, performative quality that is often held up as a signal of “true education” or “authentic learning.”

So with Barry as my inspiration, allow me to propose a term of my own: ladies and gentlemen, I give you “rote creativity.” (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Feb 18, 2020 | Phonics

Attention! This post has moved.

It can now be found at: https://www.breakingthecode.com/names-places-and-phonics/

by Erica L. Meltzer | Feb 5, 2020 | Blog, College Admissions, SAT II

I was browsing through the admissions section of Inside Higher Ed recently when I came across a brief article announcing that Caltech had decided to move from requiring two SAT IIs (one math and one science) to making the exams optional. Now, over the last few years virtually every selective college—with the exception of a few engineering schools—has downgraded SAT from “required” to “recommended.” The fact that one more school is jumping on the bandwagon might not seem particularly noteworthy, just one incidence of the backlash against standardized testing.

Because the story involves Caltech in particular, however, it’s somewhat more interesting than it might at first appear. Not only because Caltech has traditionally been seen as a bastion of uncompromising rigor, but also because it’s difficult to see the move as separable from the school’s downward trajectory in the US News and World Report Ranking over the past 20 years, especially over the last decade. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jan 1, 2020 | Issues in Education

A while back, a colleague recounted to me the following story: On the train to school one morning she found herself sitting next to a fellow teacher, one who taught AP® Government. They chatted about their classes and upcoming exams, and at one point her colleague began lamenting the fact that he was forced to make students learn facts like, say, the number of members in the House of Representatives. As he explained, his former students wrote to him with great enthusiasm about the political science courses they were taking in college. Why, he wondered, couldn’t he teach a course that generated that kind of excitement in students? Why couldn’t he just skip to the good stuff and focus on “real learning”?

I can’t say I was surprised by their conversation: I’m perfectly familiar with the trope of the teacher who proudly proclaims that it doesn’t matter whether students remember whatthey learned in his class—what really counts is the love of the subject and perhaps the habits of mind they acquired, not all those pesky little facts. But the incident stuck in my mind, and it also prompted me to finally try to put down some things that I’ve been trying to find a way to convey in less than a book-length post for a very, very long time now.

When I first discovered E.D. Hirsch’s work back about seven or eight years ago, I was already well acquainted with the deep-seated anti-intellectualism that runs through American society, but I did not fully grasp the extent to which facts themselves were maligned within the educational system. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 14, 2019 | Blog, Phonics

Let me start here.

A while back, a colleague told me the following anecdote: a college classmate of her partner was visiting from San Francisco, and the three of them had dinner together. At some point, the conversation turned toward the classmate’s middle school-aged son, who had an interest in STEM, and the classmate said something along the lines of, “Isn’t it great that schools count computer science as a language now?”

“Wait,” my colleague replied. “Languages have four main components: reading, writing, listening, and speaking. CS has the reading and writing aspects but not the other two pieces. It’s not really a language in that sense.”

The classmate was taken aback. No one in the Bay Area had ever challenged him on that point—it was just taken as an article of faith that learning to code was an acceptable (and likely superior) alternative to learning, say, Spanish.

“Whoa,” he said, “I’ll have to think about that one.”

That’s part one.

Part two is that last November, Richard was kind enough to let me observe at the Fluency Factory, and as I observed him and his tutors work, that story kept coming back to me.

On my first day there, before I watched any actual teaching, I got into a conversation with a tutor who also worked as classroom teacher. As we talked about the kinds of reading issues she encountered, she mentioned that at the international school in South America where she had student-taught, the teacher she worked with required students to stop and think before speaking.

Initially, the kids were baffled, the tutor explained. They weren’t angry, just perplexed. They were accustomed to just sounding off automatically about whatever happened to pop into their heads; no one had ever insisted that they consider their thoughts carefully before talking. But they learned to do it. These kids were six and seven years old, and reading/writing really well in both Spanish and English.

Over the next few days, I watched the Fluency Factory tutors work valiantly with lots of struggling readers, generally between the ages of seven and thirteen. In a lot of ways, it was like a redux of all of the issues I saw as a tutor: misreading words, skipping words, skipping lines, guessing at unfamiliar words, vocabulary problems, background-knowledge problems…

I was consistently stunned by the similarities between these younger students and some of my own former students, who were high school juniors and seniors. I had known in some abstract sense that they were reading at perhaps a seventh-grade level, but watching those tutors have the exact same conversations I had had with my students, except with actual middle-schoolers (and again, a mostly affluent group), drove home the extent to which those students had been stunted academically. It also made me wonder about how bad things were with the kids who weren’t getting any intervention.

The other thing that repeatedly struck me was the students’ difficulty in reading aloud.

During the last couple of years that I tutored, after I had learned a certain amount about phonics and gotten a decent sense of what sorts of problems to look out for, I began asking new students scoring below a certain threshold—usually about 550 on the SAT, 24 or so on the ACT—to read out loud for me so that I could see whether they omitted/inserted/confused words, or guessed on unfamiliar terms. What I didn’t really focus on, however, was prosody—that is, whether they could read with conversational intonation.

As I listened to Fluency Factory students read, however, I couldn’t help but notice how jerky their speech was: they paid almost no attention to punctuation, nor did they seem to recognize where the pauses and emphases within a sentence would naturally occur.

They were opening their mouths and words were coming out, but the act had nothing to do with real speech.

It was as.

If they had.

No.

Concept of where thoughts.

Began and.

Ended.

Or, for that matter, that written language was even intended to convey thoughts.

For the youngest/weakest students, I chalked this up to the fact that the mere act of decoding required so much brainpower that they had nothing left over to make sense of what they were reading, never mind doing the two simultaneously.

But the older kids mostly read this way too, and it started to freak me out a little.

It was as if, at some level, they did not really grasp that reading is written speech.

Assuming that their out-loud reading was a general approximation of their silent reading, that certainly explained a lot of their comprehension problems.

Of course, I understood intellectually that they were not reading this way on purpose, that what I was hearing was a result of their cognitive overload, but on a visceral level I found it really disturbing to hear language fragmented in that particular manner.

On multiple occasions, I realized that the jerkiness had become so ingrained in my ear that I almost started talking that way.

At any rate, it was striking to watch how their reading immediately became more fluent when they took turns reading with a tutor. They seemed to absorb the more conversational tone by osmosis. Had decoding been the only issue, that wouldn’t have happened—it wasn’t as if they were merely repeating the same words after the tutor. Yet when they reread the passage aloud again, this time entirely on their own, those gains inevitably evaporated after a couple of sentences.

I’ve written a fair amount about the connection between reading and listening, but until now, I haven’t thought quite so much about the connection between reading and speaking. I think, however, that it’s yet another piece of the reading puzzle—and a seriously neglected one at that.

As I’ve pointed out before, the language that appears in written texts is often very different from spoken language. It tends to be more syntactically complex and to contain vocabulary that students don’t necessarily encounter in everyday life. As a result, it’s hardly a surprise that even very competent decoders can have difficulty recognizing how a given line of text would be spoken (as I saw constantly when I was tutoring the SAT). And as texts become increasingly complex as students advance through the middle grades, they become increasingly divorced from spoken language.

When I wrote about this issue before, I approached it only in terms of listening: my question was whether the denigration (and in some cases the outright prohibition) of direct, teacher-led instruction, and the obsessive emphasis on student-centered groupwork, had inadvertently inhibited students’ exposure to the kind of formal, structured adult speech that bridges the gap to more sophisticated written language.

I still think that’s a major problem, but now I have to wonder whether the type of speech students are expected to produce isn’t also playing a role. If students generally have little opportunity to listen to the type of speech that overlaps with written language, then they have even less experience creating it.

In other words, if students are primarily addressing their peers informally during class—and rarely or never required to, say, give structured presentations to their entire class or (horror of horrors) sit for oral exams—then they are also not getting practice in producing the type of speech that approximates writing. And if the spoken-written connection is never fully made and/or reinforced, students then have difficulty translating words on a page into something resembling conversational speech. Lack of exposure to sophisticated texts in turn further inhibits the development of their speech, and a vicious cycle ensues.

When this idea occurred to me, I couldn’t help but contrast the pedagogies that currently dominate in the American educational system with those of France and especially Italy, countries where there is a significant emphasis on oral presentations and exams at the secondary level. (I don’t have the same level of familiarity with any other country’s school system, so I can’t comment on what it’s like elsewhere.) Students are expected to address their classmates as well as adults using formal, structured language, and to present their ideas orally with a striking degree of eloquence using—this is key—linguistic features otherwise found only in academic writing (e.g., “We have seen x and will now turn to a consideration of y…”).

That’s not to say that French teenagers don’t still mumble incomprehensibly sometimes (and boy can they mumble!), but at a systemic level, it’s a different mindset and set of expectations. And regardless of the drawbacks these systems may have—and I am by no means suggesting they are above reproach—it’s hard to deny that they are set up, on a broad scale, to systematically inculcate a particular set of verbal capacities from multiple angles and in mutually reinforcing ways.

Indeed, when listening to French adults discuss, say, politics or philosophy (or wine), it’s hard not to notice how closely their speech contains what are often only written constructions. The relationship between the various aspects of reading and speaking and, ultimately, thinking is evident, in a way that makes the links impossible to ignore.

All this is to say that I no longer believe that reading is the “three-dimensional problem” that it has traditionally been described as. Rather, I think it’s even more complex. As is true for any language, becoming truly proficient in English requires mastery of four domains—speaking, listening, reading, and writing—that build on and feed into one another. And the tendency to treat reading as a skill that can be acquired in isolation, without significant work on the other three domains, is even more of a fool’s errand than I understood even just a short while ago.