by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 1, 2021 | Blog, ESL, GMAT, Grammar (SAT & ACT), IELTS

I originally did this list as an Instagram post, but then it occurred to me that I should put it up here as well, so here goes in slightly expanded form.

First, remember that the singular/plural rule for verbs is the opposite of the rule for nouns:

Third-person singular verbs end in -s (it works, s/he does, the graph shows).

Third-person plural verbs do not end in -s (they work, they do, the graphs show).

1) Compound subject = plural

A compound noun consists of two nouns joined by and. These subjects are always plural, regardless of whether the individual nouns are singular or plural. This rule is easy in principle but can be surprisingly difficult in practice.

Correct: A stressful atmosphere and poor management are often responsible for employee burnout.

Incorrect: A stressful atmosphere and poor management is often responsible for employee burnout. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jun 3, 2021 | Blog, Grammar (SAT & ACT), IELTS

There are three main types of conjunctions in English. Some words in different categories have identical meanings, but they have different grammatical functions. As a result, they are punctuated differently when used to begin a clause or sentence.

Although the conjunctions discussed below may also appear in the middle or at the end of a sentence in certain contexts, this post concerns their placement at the start of a sentence or clause only.

1) Coordinating Conjunctions (“FANBOYS”)

There are seven coordinating conjunctions, known collectively by the acronym FANBOYS:

These words are placed in the middle of a sentence to join two independent clauses and should follow a comma. Although the punctuation is often omitted in everyday writing, you should make an effort to use it because the comma serves to clearly separate the parts of the sentence and helps the reader follow your ideas more easily. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | May 31, 2021 | GMAT, Grammar (SAT & ACT), IELTS

Image by TypoArt BS, Shutterstock

I was looking back through my grammar posts the other day when I made a rather startling discovery: in all my years of writing this blog, I had somehow neglected to write a piece covering the two major causes of comma splices.

I suspect that because I’ve given this explanation in a total of five books now, I took it for granted that I had covered both issues in a single post, back in… oh, I don’t know… 2012 maybe? But apparently not.

Since this is among the most frequently tested concepts on the SAT and the ACT, an occasional target of questions on the GMAT, and a HUGELY common error in IELTS essays, I would count this omission among the greatest oversights in Critical Reader history.

So here goes. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | May 13, 2021 | Blog, GMAT, Grammar (SAT & ACT), IELTS

Image by Charlotte May from Pexels

In theory, parallel structure is a relatively easy concept to master: it simply refers to the fact that items in a list, as well as constructions on either side of a conjunction such as and or but, should be kept in the same format (all nouns or all verbs).

In very simple sentences, e.g., I went to bed late but woke up early, this rule is generally quite simple to apply.

When sentences are long and contain a lot of information, however, things get a bit trickier. Keeping forms parallel requires the writer to keep track of and understand how words and phrases in different parts of a sentence relate to one another.

One very common issue involves the use of main verbs after modal verbs such as can, should, or might. As anyone who speaks English at a reasonably high level knows, main verbs are never conjugated in this construction, e.g., one would say it might work, not it might works. But when the two verbs are separated, there’s a common tendency forget about the first one and to stick an -s on the second.

This is an issue that appears in the writing of both native and non-native English speakers, but it’s particularly rampant in IELTS essays. It may also be tested in GMAT Sentence Corrections. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 21, 2017 | Blog, GMAT, Grammar (SAT & ACT)

As part of my attempt to make thecriticalreader.com the official repository of all things related to SAT, ACT, and GMAT grammar, I’ve posted lists of preposition-based idioms for those tests. (For now, they’re the same as the ones in my SAT, ACT, and GMAT grammar books, but I will update them if I come across additional tests with other examples.)

For SAT/ACT idioms, click here.

For GMAT idioms, click here. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 1, 2015 | Blog, Grammar (SAT & ACT)

Although I can be a stickler for grammar (a tendency that I do my best to keep in check in non-teaching/blogging/grammar book-writing) life), there are nevertheless a handful of “rules” that I really and truly could not care less about. Among them are split infinitives (a ridiculous attempt to treat English like a purely Latin-based language that fails to take its Germanic roots into account); the use of “they” to refer to a singular noun when gender is not specified (no, “he” is not actually neutral, and seeing it used that way increasingly feels like an anachronism); and the prohibition against the passive voice.

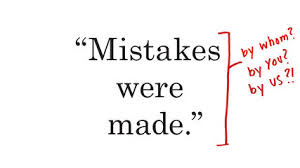

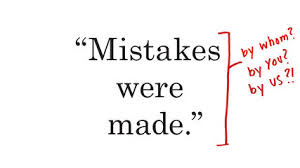

The passive voice, in case you’re unfamiliar with the term, involves flipping the subject and object of a sentence around to emphasize that an action was performed by someone/something, e.g “The man drank the water,” becomes “The water was drunk by the man.” It is also possible to omit the “by” part and simply say “The water was drunk,” the implication clearly being that it was drunk by someone.

On the SAT and the ACT, answers that contain passive constructions are almost always wrong, if for no reason other than that they tend to be unnecessarily wordy and awkward. And in fact, passive constructions are by definition wordier than active ones. The awkward part… Well, that’s up for debate.

The use of the passive voice is an issue that blurs the line between grammar and style; there are instances in which the passive creates wordy, awkward horrors, but there are also cases in which it is useful to create a particular emphasis. For example, most people would never even be tempted to say “The car keys were lost by my mother.” On the other hand, it sounds perfectly normal to say “The bill was passed by Congress yesterday” — the emphasis is on the fact that the bill went through.

I always assumed that the “no passive” rule was simply something that had been cooked up a couple of centuries ago by linguistic purists (much like the “no split infinitives rule”) and handed down from masters to disciples through the ages. In this case, however, “through the ages” means more like “since the 1950s,” more specifically since the popularization of The Elements of Style.

Now, I confess to having a soft spot for Strunk and White’s chef d’oeuvre. It was the first grammar book I used in high school English class (we were handed copies in September and instructed to memorize it — progressive education this was not), and it introduced me to all sorts of wonders like non-essential clauses and the requisite semicolon before “however” at the start of a clause.

As I recently discovered, though, Strunk and White got some things wrong. As is, major, big-time, crash and burn wrong. (In my own defense, I haven’t looked at the book in years). I knew that some people had “issues” with the “little book” — to put it diplomatically — but I always wrote that off as a matter of personal taste. Then, a couple of days ago, I stumbled across Geoffrey Pullum’s delightfully titled Chronicle Review article “Fifty Years of Stupid Grammar Advice,” in which the author takes it upon himself to enumerate the ways in which Strunk and White managed to mangle their explanation of the passive voice. Indeed, they barely understood it themselves.

As Pullum points out:

What concerns me is that the bias against the passive is being retailed by a pair of authors so grammatically clueless that they don’t know what is a passive construction and what isn’t. Of the four pairs of examples offered to show readers what to avoid and how to correct it, a staggering three out of the four are mistaken diagnoses. “At dawn the crowing of a rooster could be heard” is correctly identified as a passive clause, but the other three are all errors:

- “There were a great number of dead leaves lying on the ground” has no sign of the passive in it anywhere.

- “It was not long before she was very sorry that she had said what she had” also contains nothing that is even reminiscent of the passive construction.

- “The reason that he left college was that his health became impaired” is presumably fingered as passive because of “impaired,” but that’s a mistake. It’s an adjective here. “Become” doesn’t allow a following passive clause. (Notice, for example, that “A new edition became issued by the publishers” is not grammatical.)

I’ve heard horror stories about college students getting marked down on papers because their TAs/professors mistakenly thought they had used the passive voice when that was not the case at all. (And at any rate, no one should get marked down just for using the passive voice.) It’s always a problem when people have knee-jerk reactions to concepts they don’t fully understand.

To be clear, though, I understand the pushback against the passive, especially on standardized tests. Standardized tests are, by nature, crude tools; their goal is to touch on the most common and misuses of various structures. I’ve read enough wordy, repetitive, marginally coherent SAT/ACT essays to last a lifetime, and given that experience, I don’t have a problem with the tests’ perhaps overzealous approach. In this case, however, know that the rule is a little more flexible in real life. But try not to go crazy, or a hard time will undoubtedly be had by your readers.