by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 23, 2015 | ACT English/SAT Writing, Blog, SAT Grammar (Old Test)

Shortcut: semicolon + and/but = wrong

If you see an answer choice on either the SAT or the ACT that places a semicolon before the word and or but, cross out that answer immediately and move on.

Why? Because a semicolon is grammatically identical to a period, and you shouldn’t start a sentence with and or but.

The slightly longer explanation: In real life, semicolon usage is a little more flexible, and the choice to use when can sometimes be more a matter of clarity/style than one of grammar. It is generally considered acceptable to place a semicolon before and or but in order to break up a very long sentence, especially when there are already multiple commas/clauses.

For example:

Pamela Meyer, a certified fraud examiner, author, and entrepreneur, became interested in the science of deception at business school workshop during which a professor detailed his findings on behaviors associated with lying; and she subsequently worked with a team of researchers to survey and analyze existing research on deception from academics, experts, law enforcement, the military, espionage and psychology.

In the above sentence, either a comma or a semicolon could be used before and. In this case, however, the sentence is so long and contains so many different parts that the semicolon is a logical choice to create stronger break between the parts.

Why not just use a period? Well, because a semicolon implies a stronger connection between the clauses than a period would; it keeps the sentence going rather than marking a full break between thoughts. Again, this is a matter of style, not grammar.

The SAT and the ACT, however, are not interested in these details. Rather, their goal is to check whether you understand the most common version of the rule. Anything beyond that would simply be too ambiguous.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 20, 2015 | Blog, General Tips, The New SAT, Tutoring

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere on this site, I’m often a tutor of last resort. That is, people find their way to me after they’ve exhausted other test-prep options (self-study, online program, private tutor) and still find themselves short of their goals. Sometimes very, very far short of their goals. When people come to me very late in the process, e.g. late spring of junior year or the summer before senior year, there’s unfortunately a limited amount that I can do. Most of it is triage at that point: finding and focusing on a handful of areas in which improvement is most likely.

Not coincidentally, many of the students in this situation who find their way to me have been cracking their heads against the SAT for months, sometimes even a year or more. Often, they’re strong math and science students whose reading and writing scores lag significantly behind their math scores, even after very substantial amounts of prep and multiple tests. They’re motivated, diligent workers, but the verbal is absolutely killing them. Basically, they’re fabulous candidates for the ACT. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 19, 2015 | Blog, The New SAT

In case you haven’t seen them, they can be downloaded https://collegereadiness.collegeboard.org/sat/practice/full-length-practice-tests

The basic formula for determining scaled scores is simple enough (count how many you got right, convert to a raw score, and multiple by 10); however, if I hadn’t witnessed some of the College Board’s recent antics, I sincerely would have thought that the subscore charts were some kind of parody.

If want a definition for convoluted (assuming you’re taking the SAT before March 2016), this pretty much sums it up. Just looking at those charts gives me a headache.

I’m sorry, but does anyone truly think that college admissions officers with thousands of applications to get through are going to even LOOK at those sub-scores?

But as everyone knows, more data is always better. Except, of course, when it isn’t.

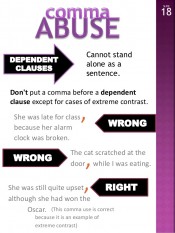

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 18, 2015 | ACT English/SAT Writing, Blog

Note: Because this post has become so popular, I’ve made it available in PDF format. Click here to download.

I’ve recently received a handful of questions asking for clarification about rule governing the use of commas with names and titles. Of all the comma rules tested on the SAT® and ACT®, this is probably the subtlest.

The good news is that questions testing this rule don’t show up very often; the bad news is that if you don’t know the rule, these questions can be very tricky to answer.

The other piece of good news, however, is that when names/titles appear in the middle of a sentence (that is, not as the first or last words), these questions can almost always be correctly answered using a simple shortcut. And if you just want to know the rule for everyday use, the shortcut is effective in the real world as well.

(more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 17, 2015 | ACT Essay, Blog

Although the ACT announced the changes to the essay last spring, I keep encountering people (including tutors) who aren’t aware of the shift. If the College Board has gone all out promoting the changes to the SAT, the ACT has been a lot more reticent about publicizing the upcoming changes. If you’re (re)taking the ACT with writing this fall, however, this is something you need to be aware of.

The ACT has always been upfront about the fact that it is necessary to include a counterargument to obtain a top score, but now that requirement is being pushed further. Instead of considering two perspectives, test-takers will now be asked to engage with three perspectives.

Click here for information about the new prompt, and here for sample essays at each score level.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 16, 2015 | Blog, SAT Essay

I’ve been saying half-jokingly for a while that the AP English Language test should take a cue from the AP language tests and include an essay that requires students to compose a formal email.

Granted, this type of assignment might seem a tad simplistic for the AP exam; however, given the redesigned SAT’s purported emphasis on “the skills that matter most,” why not test one of the skills that does incontrovertibly matter most in the hyper-competitive knowledge-based twenty first century economy?

As I wrote about the other day, in light of some of the emails I’ve received, I actually think that this would be a rather challenging assignment for many high school students. Among other things, it would not only require correct grammar and diction (points off for all lower-case!) but also use of a formal register.

And come on, how often in the real world do people really get asked to write an essay analyzing how an author builds an argument? Not very often, I should think — especially if they’re busy inventing the next great app for something that will truly benefit society, like faster pizza delivery.

And since liberal arts education is being dismantled anyway, why not simply do away with the pretense that it matters and test students on a skill that might actually help them land a job?

The assignment would go something like this (adapted from the French AP):

You will reply to an email message. You have 15 minutes to read the prompt and write your response.

Your response should include a greeting and a closing and should respond to all the questions and requests in the message. In your reply, you should also ask for more details about something mentioned in the message. Also, you should use a formal form of address. (Apparently, the people who write the directions for the AP exams never learned that you’re not supposed to start a sentence with “also.”)

Introduction

This is a message from Jane Smith, who directs a program that places high school students in internships with local businesses. You are receiving this message because you have indicated your interest in this program. The message is being sent to find out more about your interests and qualifications.

From: Jane Smith

To: Internship applicants

Dear Applicants,

We are excited to learn of your interest in participating in our program! For the last 10 years, we have offered high school students the chance to hone their career readiness skills for success in the twenty-first century economy. In order to determine whether you are a good fit for our program, we ask you to provide some additional information.

What attracts you to our program, how do you believe you will benefit from it, and what sorts of skills could you bring to a twenty-first century workplace?

What is your schedule: are you available on weekdays and/or weekends? How many hours can you work each day, and do you have any flexibility?

Which sectors appeal to you most, and why do they appeal to you?

We eagerly await your response.

Sincerely,

Jane Smith

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 14, 2015 | Blog

As I wrote about recently, I’ve seen a recent uptick in email. In addition to requests for my books, I also receive everything from straight up fan mail (always exciting), while others involve questions or comments.

Now, some of these missives are absolutely lovely. The writing is not only grammatically correct but also polite, clear, and fluid, and could easily have been produced by someone a decade or two older. I assume that even if these kids don’t get into fill-in-the-blank-Ivy, they’ll most likely be fine in life since anyone who has mastered the rules of written communication at 16 or 17 will almost certainly be able to find a job doing something or other. If these letters include a request, I usually try to answer them when I have a moment and am not so mentally burned out that I can’t manage to string five or six sentences together.

Alas, other emails are, to put it bluntly, sloppy and ungrammatical, some with a whiff of entitlement.

To be clear, I am not talking about typos, which everyone makes, nor am I referring to understandable errors made by people whose first language is not English. It takes some serious gumption to write in a foreign language, and far more gumption to even contemplate applying to college in a foreign country. In addition, I’m aware that certain rhetorical flourishes common in some languages can translate awkwardly into English. Those don’t concern me here.

For the record, I am also not looking to pick apart anyone’s writing in the course of a normal email exchange. Yes, I write grammar books, but there’s a time and a place for everything, and I know how and when to shelve it. If you have a question, by all means write to me — I’m not trying to scare anyone off.

That said, I’m also not letting people entirely off the hook here. If you know English well enough to be aiming for a high score on the SAT, and to apply to study in the United States at the university level, chances are that you know English well enough to follow its most basic rules. And if English is your first language, or if you’ve been going to an English-language school for years, you really have no excuse. The assumption on the reader’s part will be that you know perfectly well how to write correctly but simply couldn’t be bothered to do so. That is not an impression you want to make. In fact, it’s just plain rude.

This may sound obvious, but the point of writing is to communicate with other people when you are not physically present. Your writing is a stand-in for you, a delegate on your behalf, if you will. And in the absence of any other information, you will be judged by it — consciously or subconsciously — because it’s all that the reader has to go on.

Furthermore, different situations call for different types of communication, and what’s perfectly acceptable in one situation might not even be remotely appropriate in another.

When you are texting your friends or posting on Facebook, it’s perfectly fine to write things like “HAHAHA ROTFLMAO!!!”

When you are writing to your parents, you can say things like “hi, ill be home at 6, when r we eating”

However: Any time you communicate in writing with an adult you do not already have an established, familiar relationship with, you are expected to write correctly. Admissions officers, college professors, and prospective employers all fall into that category. If you’re not sure, err on the side of caution. Trust me when I say that no one cares whether you got an 800 in Writing if you cannot actually express yourself in clear, coherent, grammatically standard English. Test scores only have meaning if they reflect what you actually know.

This does not mean you need to be stylistically brilliant, nor does it mean you need to pack your writing full of ten-dollar words and use convoluted sentences that are five lines long. It does, however, mean that you are expected to follow the conventions of standard written English (electronic) communication.

These include:

- Capitalizing the first letter of every sentence, proper names, and the word “I.” Moreover, capitalization must be consistent — you can’t capitalize in some places and use lower case in others. It is almost impossible to overemphasize how sloppy that looks. (It also comes off as a little unstable.)

- Ensuring that your writing does not contain any egregious grammatical errors — that means things like comma splices. Most people aren’t interested in picking apart your grammar, but they will notice if your mistakes are glaring.

- Phrasing things politely and recognizing that people will not necessarily be able to accommodate you simply because you’re making a request.

And if you really want to make a good impression:

- Separating ideas with a space between paragraphs. Large blocks of text can be extremely difficult to process mentally, especially on a screen. Creating clear visual divisions between thoughts makes your ideas easier to follow.

Perhaps I’m turning into an old curmudgeon, or perhaps capitalization is just a relic that can’t be seriously expected of 21st century students (who are presumably all going to become superstar coders who have no need to write anything), but I’m not quite willing to throw in that towel just yet.

In some ways, I feel bad for picking on people for this — some of the emails I receive are terribly, almost painfully sweet. When I jotted down the first handful of exercises that would eventually become The Ultimate Guide to SAT® Grammar, I had absolutely no idea that my books would help students in places like Egypt and Tunisia fulfill their dreams of studying in the United States. I’m staggered by their impact, and I’m truly sorry that there are limits to how I can distribute them. But on the other hand, it seems like a disservice not to point these things out, and not (only) for the sake of being a nitpicky grammarian.

I think that this problem seems particularly acute to me precisely because I’m not a teacher. Website aside, pretty much all of the people I exchange emails with are other adults (of varying degrees of education, I might add) who invariably follow the basic standard rules of written English — even in a casual, two sentence exchange. It’s therefore very striking — and irritating — to me to receive an email that does not contain a single capitalized letter. I’m also not subject to administrators or educational fads that subscribe to the belief that it’s normal or acceptable for high school juniors to write like fifth graders.

Given the obsession with “real world skills,” I find it frankly bizarre that schools are not actually impressing upon their students the importance of mastering this exceedingly fundamental real world skill. But as someone who’s basically made a career out of teaching very important (basic) things that no longer get taught in school, I feel responsible for bringing it to people’s attention.

The reality is that in college, in the professional world, the ability to express yourself well still counts enormously. Like it or not, poor writing will reflect poorly on you. You have no idea what sorts of opportunities you might miss out on simply because you made a questionable impression. You also have no idea whose hands your emails might end up in; the “Forward” button is a powerful tool. If you are the one-in-a-million exception who starts the next Facebook, you’ll get a pass. Otherwise, you probably won’t.

So in the immortal words of adults everywhere, I’m not just trying to be mean; I’m actually doing you a favor.

Someday, you’ll thank me for it.

(For further reference about what will be expected from you in college, see https://www.math.uh.edu/~tomforde/Email-Etiquette.html. Note that this was written by a MATH professor.)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 13, 2015 | Blog

The Critical Reader, 2nd Edition is tailored to the redesigned SAT. Like the previous version, this edition balances critical aspects of comprehension with SAT-specific strategies. While a significant amount of information from the first edition has been left intact, this edition also features extensive discussions of supporting evidence and infographic questions, along with numerous full-length passages that reflect the new test’s heavier focus on science and social science.

With the exception of those excerpted from historical documents, passages are taken from contemporary sources including The Economist and Harvard Business Review, and are closely matched to the style and level of the passages on the exams released thus far by the College Board.

Click here to purchase.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 10, 2015 | Blog

In recent days, I’ve received an increasing number of emails from people in various countries requesting PDF versions of my books, often for free. Their reasons range from the perfectly valid to the somewhat questionable to the frankly clueless.

Unfortunately, I cannot accommodate these requests, no matter how compelling the reasons.

Let me explain. I am not denying these requests for the sake of being difficult, or stingy, or cold-hearted. Rather, the reasons have to do with the logistics and economics of self-publishing in the digital age.

First, my SAT grammar book (albeit the original version) is available for Kindle download through Amazon. I’m not sure what the international restrictions are, if any, but in theory it should be downloadable from just about anywhere.

As for The Critical Reader, I am legally prohibited from distributing it electronically. The book contains passages taken from a number of copyrighted sources, and in order to include them, I had to obtain legal permission from various rights holders — a process that involved dozens of emails, several thousand dollars, and, in several cases, waiting periods upwards of six months. Most of the contracts granting me the reprint rights to the passages stipulate that I may only distribute a print version of the book. Sending out PDFs of the book would be a breach of contract on my end, and could result in my being sued for thousands or even millions of dollars.

In addition, please consider this: my books represent months and in some cases years of work. They are the result of thousands — literally, thousands — of hours of unpaid work. The second I put my in someone else’s hands I lose control over its distribution. It takes half a second to hit the “forward” button and send a PDF to someone else, who in turn sends it to another couple of people, who all send it to another couple of people, on of whom posts the entire 380-page file on College Confidential for free download — as I’ve seen happen with other books.

Aside from the lost royalties, when (if) I discover that my books have been distributed on the Internet and do nothing, I am at risking for losing my copyright — that is, I could potentially lose the rights to my own work, which I spent all of those years producing. In order to protect it, I have no choice but to take very expensive legal action.

I am in the process of investigating ebook options. If I am able to find a relatively straightforward means of having a secure electronic version of The Critical Reader created, then it may be worthwhile for me to go back to the various publishers I am beholden to and request electronic rights. But that will be a longterm process. In the meantime, there are risks I simply can’t afford to take.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 5, 2015 | Blog, Issues in Education

In theory, at least, I should be the very last person to weigh in on this topic. As I usually joke, most of my students could tutor me in math. My mathematical education was mediocre in every way imaginable, and let’s not even talk about that 200+ point score gap between my SAT and Math and Verbal scores. With competent instruction, I probably could have become an excellent — or at least a decent — math student, but alas, that ship sailed many years ago.

So why on earth should anyone listen to me spout off about what ails math education? Well, because by this point, I know a fair amount about the functions and dysfunctions of the American educational system, about pedagogical trends, and about just how difficult good teaching really is. If you’re willing to hear me out, I’m going to start with an anecdote. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jul 25, 2015 | Blog, SAT Grammar (Old Test)

So after months of living under a rock in a desperate attempt to finish my revised SAT books in time for the summer stampede, I’m finally taking a few tentative steps into the sunlight.

Several of you have written to me lamenting my lack of acerbic commentary on the June SAT scoring scandal, the new SAT, and other educational embarrassments, and I promise you that I am well aware of that shortcoming. Rest assured that I do in fact have many, many things to say; I’ve merely had to devote every last brain cell to rewriting my books for the last half-year, leaving me precious little room for other thoughts, acerbic or otherwise. I’m hoping to begin posting some commentary here in the next weeks.

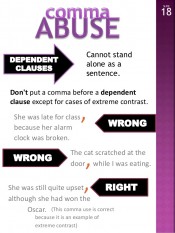

For the moment, though, I want to address a topic that a couple of people have written to me about recently, namely the “no comma before ‘because’ or ‘since’ rule.”

Actually, it’s not really a “rule” per se. It’s more of a guideline. In the universe of SAT grammar errors, it’s a pretty minor one, and for that reason it’s pretty certain that an answer’s correctness/incorrectness will never depend exclusively on it. It’s merely a secondary consideration.

Let me back up and explain.

There are two main types of conjunction: coordinating and subordinating.

Coordinating conjunctions (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so) are also known by the acronym FANBOYS. They can be used to join two independent clauses (complete sentences) and must always follow a comma when employed in this way.

Correct: The city’s government has curtailed spending on all non-essential services, so the new theater company has been forced to suspend its productions for lack of funding.

A FANBOYS conjunction can only be used at the start of the second clause; it cannot be used at the start of the first. Even if you don’t know the grammatical rule, you should be able to recognize that this usage does not make any sense.

Incorrect: So the new theater company has been forced to suspend its productions for lack of funding, the city’s government has curtailed spending on all non-essential services.

Subordinating conjunctions on the other hand, can be used to start either the first or the second clause. Common subordinating conjunctions include because, while, since, when, until, and unless.

Now, here’s the rub. If you are being absolutely, technically correct, a comma should be used to separate two clauses when the clause begun by the subordinating conjunction comes first.

Correct: Because/Since the city’s government has curtailed spending on all non-essential services COMMA the new theater company has been forced to suspend its productions for lack of funding.

When the clause begun by the subordinating conjunction comes second, no comma should be used (although there is an exception for “strong” subordinating conjunctions such as although and even though, which do take a comma).

Incorrect: The new theater company has been forced to suspend its productions for lack of funding COMMA because/since the city’s government has curtailed spending on all non-essential services.

Correct: The new theater company has been forced to suspend its productions for lack of funding NO COMMA because/since the city’s government has curtailed spending on all non-essential services.

That’s the strict version of the rule. The more complicated truth is that it depends on context: if a sentence is very long, or it seems necessary to insert a comma before because in order to make the meaning of the sentence clear, then that construction is acceptable.

From what I’ve observed, the College Board/ETS/whoever it is setting the rules tends to adhere to the strict version: answers that contain the construction comma + because/since are pretty much always wrong. (Please note that this pattern was observed in regards to the pre-2016 SAT only.)

That said, wrong answers with that construction almost always contain an additional problem that makes them absolutely, incontrovertibly wrong. So maybe it’s more correlation, not causation.

A while back, someone contacted me about a question in the online program that violated that rule; an answer with the construction comma + because was correct. That did make me rethink things, but only up to a point. I’ve found slight inconsistencies between the online tests and real tests in the past, and I’ve never seen a question from an administered test that broke this “rule” (although if anyone reading this post has seen one, please let me know!).

My suggestion, therefore, is to work from the standpoint that any answer with the construction comma + because/since is probably wrong, and only reevaluate that assumption if there’s a clear grammatical problem with every other answer. To be fair, the SAT does break its own “rules” sometimes, and this one isn’t particularly hard and fast. But still, you’re better off playing the odds and working from there.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jul 22, 2015 | Blog

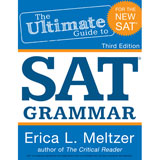

For those of you planning to take the new SAT, The Ultimate Guide to SAT® Grammar, 3rd Edition, is now available on Amazon. The book covers all of the grammar and rhetoric concepts tested on the new exam, and includes an index of Official Guide/Khan Academy questions grouped both by category and by test.

Click here to purchase.

The Critical Reader, 2nd Edition, should be available through CreateSpace within the next week and on Amazon by early-mid August.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jun 13, 2015 | Blog

For those of you who absolutely can’t wait a few more weeks to get started studying for the new exam, I am planning to make (unproofed pre-publication copies of The Ultimate Guide to SAT® Grammar, 3rd Ed. available for purchase through CreateSpace sometime this week for a reduced price of $19.95. If you’d prefer to wait a few weeks for the final, proofed version, I’m hoping to make it available on Amazon in early July.

The book provides a comprehensive overview of all of the grammar and rhetoric topics tested on the redesigned test, as well as numerous exercises designed to hep students apply individual concepts to test-style questions.

At just over 250 pages, it is somewhat longer than the previous editions (partly because of the inclusion of more test-style questions) but still concise enough to be manageable.

As in the previous editions, the book includes two complete indices of College Board questions (full-length SATs recently posted on Khan Academy): one organizing concepts by category, and one organizing them by test. These tests will also be included in the forthcoming Official College Board Guide.

I will post notification as soon as the book is available for purchase.

Note: Because the new SAT Writing section is so similar to the ACT English test, there is some overlap between this book and The Complete Guide to ACT English. That said, all of the material is tailored to the specifics of the new SAT.

I am doing my best to finish revising The Critical Reader by the end of this month. I am hoping to make pre-publication copies available sometime in early-mid July, with the goal of having the book on Amazon by the end of that month.

The Ultimate Guide to SAT® Grammar Workbook, 3rd ed., will most likely be available in the late summer or early fall, although I am considering making individual tests available as they are completed.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jun 12, 2015 | ACT Reading, Blog

I recently noticed that a couple of my students were kept missing ACT reading comp questions that should have been very straightforward. Their reading was strong enough that they shouldn’t have been getting those questions wrong, and at first I wasn’t sure why they were having trouble. Upon closer inspection, however, I realized that the questions giving them trouble consistently had answers located in the introduction.

What I suspect was happening was this: they saw a question without a line reference, and if they didn’t remember the answer, their immediate reaction was to panic and (subconsciously) assume that the answer was going to be buried somewhere in the middle of the passage — somewhere very difficult to find. Basically, they were so used to assuming that things would be hard that it never occurred to them that they might actually be easy!

Had they simply scanned for the key word/phrase starting in the introduction and skimmed chronologically, they would have found the answer almost immediately. Inevitably, when I had them re-work through the questions that way, they had no problem answering them correctly.

So if you find yourself confronted with a straightforward, factual reading comprehension without a line reference and have absolutely no recollection of where the answer is located, don’t just jump to somewhere in the middle of the passage and start looking around.

Instead, figure out what word or phrase you’re looking for, and start scanning quickly for it from the very first sentence, pulling your finger down the page as you scan to focus your eye and prevent you from overlooking key information. You might come across the answer a lot faster than you’re expecting.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jun 11, 2015 | ACT English/SAT Writing, Blog

I think we can probably all agree here that whatever the strengths of the ACT English section may be, formatting is most definitely not one of them. When there are five or six spaces — or even half a page — between lines, it’s almost impossible not to sometimes lose track of where paragraphs begin and end. Since I started tutoring the ACT in 2008, I’ve spent who knows how much time explaining just where the sentence is supposed to be inserted, or which paragraph a little numbered box is actually referring to. Sooner or later, almost every ACT student of mine has missed a question simply because they couldn’t figure what they were supposed to fix where.

Beyond the most obvious instances of formatting-related mistakes, though, I’ve noticed some subtler errors. One problem that seems to come up again and again involves…page turns. When I work through the same tests with enough people, I inevitably start to notice that almost everyone gets certain questions wrong, usually for the same reasons.

A couple of tests that I regularly use have questions that bridge two pages — that is, the sentence that a question asks about begins at the bottom of one page and ends at the top of the next page. Sometimes, it’s a very long sentence, which means it’s easy to lose track of.

And very often, my students answer those questions incorrectly because they’ve only read the information on the page containing the underlined portion or numbered box.They either didn’t want to make the effort to back up a page and read from the beginning of the sentence (relatively rare) or, more frequently, were so focused on the underlined portion of the sentence that they didn’t realize it actually began on the previous page.

Ironically, focusing on the question so hard caused them to overlook the larger context and miss the very information that they needed to answer the question. Had the entire sentence been located on a single page, they would likely have read from the start of it; but because it was split up, they simply didn’t notice that they weren’t reading from the beginning.

The moral of the story? Always, always back up and read from the beginning of the sentence, actively identifying where that place is. The capitalized letter at the beginning of a word is a giveaway, and no, I’m not being sarcastic. Sometimes you have to be that literal.

Recently, I’ve started seeing the same problem with paragraphs and rhetoric questions, specifically adding/delete sentences questions. In order to determine whether information should be added or deleted — that is, whether it’s relevant to a paragraph — it is first necessary to know what that paragraph is about. What part of the paragraph tells you most directly what it’s going to be about? Often, the first (topic) sentence or couple of sentences.

When the first sentence is on the previous page, however, it’s suddenly a lot less intuitive to read that spot. And when lines are separated by multiple spaces, making only a few lines of text appear much longer, it is possible to not even realize that a paragraph begins on the previous page. Again, the best way to guard against this problem is to back up and consciously search for the indented line that always signal the beginning of a paragraph, keeping in mind that it may be on the previous page.

Working this way might seem like an inordinate amount of effort — one more little detail to think about, on top of everything else — but it can actually save you time and energy in the long run. Instead of trying to puzzle out an answer that you don’t have sufficient information to determine, flipping back a page and getting the full picture can actually make finding the answer much more straightforward.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jun 5, 2015 | Blog, The Mental Game

For those of you taking the SAT tomorrow (and scouring the Internet for a few last-minute tips), here’s a small one that could actually have a significant effect on your score.

To introduce it, a personal anecdote (notice how many time the word I appears in the following sentences). About five years ago, I was going over a student’s QAS score sheet from her first real SAT. She was a good student and strong test taker, and in fact she’d scored a 2200. It was pretty much in line with her practice tests, but when I looked at the scoring breakdown by section, something leapt out at me: virtually every question she had gotten wrong came from the first three sections. And when I read over her essay, I saw that it was, well… Let us say it was not her best work.

At that point, I put two and two together. “G,” I said pointedly. “Were you awake when you started this test?” (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Apr 17, 2015 | ACT English/SAT Writing, Blog

Much as I’ve tried to cut back on tutoring to work on my seemingly endless SAT book revisions, I somehow haven’t been able to escape entirely. In fact, I somehow ended up with no fewer than five (!) students taking the ACT this Saturday. It’s therefore entirely unsurprising that I’ve had the same set of conversations repeatedly over the last couple of weeks. (It’s also entirely unsurprising that I can no longer remember which conversation I’ve had with whom and am therefore reduced to constantly asking the student in front of me whether we’ve already discussed a particular rule, or whether I actually gave the explanation to someone. Although actually I’ve been doing that for a while now.)

Perhaps not unexpectedly at this point in the year, almost all of my students were “second rounders” — people who had worked with other tutors, for months in some cases, before finding their way to me. And that meant that there was the inevitable psychological baggage that accumulates when someone has already taken the test a couple of times without reaching their goals. As a result, I’ve been paying just as much attention to how people work through the test. When I work with a student who actually does have most of the skills they need but can’t quite seem to apply them when it counts, that’s basically a given.

It’s interesting — I’ve never really bought into a lot of the whole “test anxiety” thing, but more and more, I find myself dealing with the psychological aspects of test taking. (But rest assured, I don’t talk about scented candles or relaxation exercises).

Anyway, over the last few weeks, I’ve found myself paying an awful lot of attention to just what people who are scoring in the mid-20s on ACT English and trying to get to 30+ do when they sit down with a test. I’m pretty good at managing the psychological games that people play with themselves, particularly when they involve second-guessing, but I’ve never spent so much time thinking about those games specifically in terms of ACT English before.

Well, there’s a first time for everything.

If there’s one salient feature that characterizes the ACT English test, it’s probably the straightforward, almost folksy Midwestern style. There’s an occasional question that really makes you think, but for the most part, what you see is what you get. A lot of wrong answers are really wrong, almost to the point of absurdity.

As I worked with my ACT students, I noticed something interesting: when the original version of a sentence (that is, the version in the passage) didn’t make sense, the student would get confused and reread the sentence or section of the passage again. And when they still didn’t understand, they’d reread it again. And sometimes a third time.

The issue wasn’t so much that they were running out of time, but rather that they were wasting huge amounts of energy trying to make sense of things that couldn’t be made sense out of because they thought they were missing something. Then they were getting confused and panicking and second-guessing themselves.

So although it might sound obvious, I think this bears saying: if you are working through an ACT English section and find that you just cannot make sense out of a phrase or sentence in the passage, that version of the phrase or sentence is wrong. Do not try to wrap your head around it by reading it again and again. You can’t make sense out of it because it doesn’t make sense. In other words, it’s not you — it’s the test.

Even if you don’t know what the right answer is, you do know what the answer is not: NO CHANGE. Pick up your pencil, put a line through A or F, and start plugging in the other options.

You might not know quite what you’re looking for, but at least that way you’re doing something constructive, not just freaking yourself out.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Mar 20, 2015 | Blog

Over the last few weeks, I’ve started to get inquiries about when I’ll be releasing my new books for the redesigned (P)SAT. Most likely, the final versions will not be ready until sometime this summer; however, I will do my best to make beta versions available in the late spring, probably May.

The books that will be revised are as follows:

- The Ultimate Guide to SAT® Grammar

- The Ultimate Guide to SAT® Grammar Workbook, most likely with eight complete Writing tests

- The Critical Reader

Unfortunately, the College Board has been extremely slow to release materials for the new exam. While I have begun revisions based on the limited sample questions they have made available thus far, my primary concern — as always — is accuracy rather than speed or quantity, and there is simply no way for me to obtain a solid understanding of the new test’s nuances without having a number of exams to study closely.

Because the new Official Guide is not scheduled for release until the end of June, and I have no means of obtaining multiple full exams sooner — there is no way for me to create publishable materials before that time. In the meantime, however, I am using the information I do have to rewrite as much as I can, hopefully leaving me with only a handful of gaps to plug with then the Official Guide is released. There is of course a chance that I will need to obtain reprint rights for new passages, in which case the final version of the Reading book may be delayed.

I will continue to post updates as I get a better idea of when my new books will become available.