by Erica L. Meltzer | Nov 20, 2021 | Reading (SAT & ACT), Tutors

I’m happy to announce that my Working with Struggling Older Readers: What Tutors Need to Know is now available at video.thecriticalreader.com. Although it is geared toward SAT/ACT tutors, it can be adapted by anyone working with struggling older readers in middle school or above.

The program includes the following:

Part 1 (53:00) covers some of the background issues that influence the reading process and that can interfere with students’ ability to connect letters on a page to authentic language. (If you’ve read my series of blog posts on this topic, some of the material will probably be familiar, but I encourage you to watch this part regardless since it summarizes the major issues and provides important context for Part 2).

Part 2 (1:47) is a step-by-step guide to a series of systematic, age-appropriate exercises designed to help older readers process sound-letter combinations more accurately and fluently so that they can focus on the meaning of what they read. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Nov 13, 2021 | Blog, IELTS

Although it is very important to make a good first impression on your examiner by writing a strong introduction to your Task 2 essay, the body paragraphs are where your overall mark will really be determined.

Body paragraphs form the substance of your essay, and so it is important that they be structured logically (Coherence and Cohesion), and in a way that allows you to respond to the question as directly and thoroughly as possible (Task Response).

Because the Writing test requires you to apply so many skills at the same time, it can be very helpful to have a standard body-paragraph “formula” that can be used for virtually any question.

Once you have determined the focus of your paragraph, each new idea can be introduced with linking device + point.

You can then discuss that point or give an example to illustrate it using no more than two additional sentences. The limit prevents repetition, over-explaining, and going off-topic.

(more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 30, 2021 | Blog, Reading (SAT & ACT), Tutoring, Tutors

Slowly but surely, I am making progress on my webinar for tutors working with struggling older readers.

After a crash course in using Zoom to record PowerPoints, numerous attempts, and much time spent finagling computer-camera angles in my office, I’ve actually managed to produce what I hope is a serviceable recording. (I was having a bad hair day in pt. 2, but I’m hoping that everyone can deal;)

There are two parts: a shorter (approx. 40 mins.) introduction part, in which I summarize some of the key issues and background information (the Simple View; the Matthew effect; the three-cueing system); and a longer recording (1:45), in which I present and demonstrate a series of short exercises based on the sequence developed by my colleague Richard McManus at the Fluency Factory in Cohasset, Mass.

Although I spend a lot of time going over the exercises, they can actually be done in about 30 mins. and can thus be split with regular test prep. I’ve also tried to actually integrate SAT/ACT-based materials into the exercises as much as possible.

I’m currently working on the materials packet (probably in the range of 70-75 pages) and will hopefully have the whole thing ready by the week of November 7th. I haven’t yet determined the overall price, but the packet will be included along with the webinar because it would be pretty ridiculous to explain all of the exercises without, you know, actually providing them. Initially, I was going to focus on the ACT since that’s the test where speed and processing issues tend to become most apparent, but because the SAT is the more popular test, I’ve integrated some material from that exam as well.

A few points: (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 16, 2021 | IELTS

Fiona Wattam at IELTS Etc. recently put up an excellent post on some of the trickier aspects of using idioms well in IELTS essays, and it got me thinking about that topic as well. I think it’s fair to say that it’s a very popular subject: a quick Google search turns up almost four million results, some of which offer very contradictory advice.

I spent a lot of time thinking about idioms while writing (and repeatedly rewriting) that section of my IELTS grammar book, and at a certain point—perhaps after my tenth revision?—I came to a realization and finally managed to put the issue into words: using idioms is not the same as speaking or writing idiomatically.

I realize that statement might sound very contradictory so, to use a frequently memorized Task 1 General Training phrase, allow me to explain:

Essentially, the problem lies in the similarity of the terms idiom and idiomatic. One could very reasonably assume that they refer to the same thing, but in reality… not quite. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 9, 2021 | Blog, Issues in Education, Phonics, Tutoring, Tutors

At the beginning of the summer, after I did my series of posts for tutors who have unexpectedly found themselves working with struggling high-school readers trying to prepare for college admissions tests, I started putting together a presentation for a webinar to address the major issues at play and demonstrate some of the exercises that can be used to help remediate such students.

Alas, my summer and the beginning of my fall got hijacked by my IELTS books, followed in rapid succession by necessary updates to my GMAT, ACT English, and ACT Reading books (followed by the IELTS again).

I’m happy to announce, however, that I finally seem to be back on track and am planning to record the webinar in the next week or so, and then people can access it at their convenience. I’m also doing my best to put together an accompanying materials pack that includes all the exercises covered. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 4, 2021 | Blog, IELTS

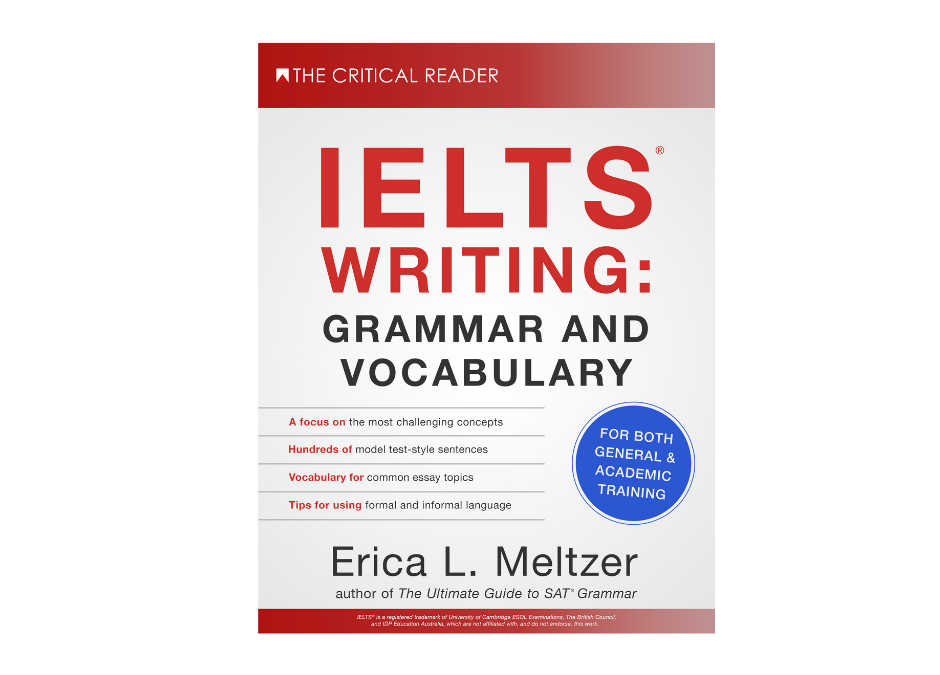

The print version of my IELTS grammar and vocabulary guide covering both Academic and General Training is now available on Amazon as well as the Books page. If you’re studying for that exam, or are a tutor who prepare students for it, here is what you need to know.

IELTS® Writing: Grammar and Vocabulary is based on a simple premise: to write a good essay, one must first be able to write well at the sentence level.

Many IELTS Writing guides focus on overall essay organization and construction and treat grammar and sentence-structure almost as an afterthought. And if they do emphasize these aspects of English, they often include example sentences that are much simpler than those required by the exam, or that are not fully relevant to the kinds of topics it involves. As for books written by non-native English speakers… well, I’m not even going to go there.

This is book is different. To the greatest extent possible, it focuses on direct application to the IELTS. It shows how specific structures are particularly suited to certain topics and scenarios, and points out traps to avoid. It also walks readers through the process of constructing “complex” sentences without losing control of their writing, and covers common errors that many test-takers do not even realize can easily (and quickly) prevent them from achieving their desired score. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jul 24, 2021 | ACT Reading, Blog

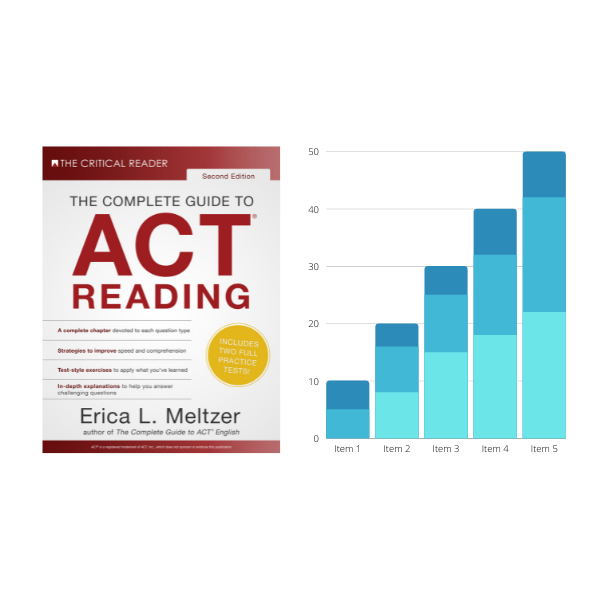

As you may have heard, the ACT is tweaking its Reading test to include some graph- or chart-based questions similar to those on the Science test and the SAT Reading test. I’ve received several inquiries regarding these changes, so I wanted to let everyone know where things stand in terms of my materials.

First, yes, I will be updating The Complete Guide to ACT Reading, although not immediately.

Unfortunately, the 2021-22 ACT Official Guide does not include any sample passages accompanied by the new question type; as of July 2021, the only example I’ve been able to locate is the one posted on the ACT website, and, well… It doesn’t seem particularly well done (to put things diplomatically). In the absence of any material from administered tests, there’s also no way for me to tell how well it reflects what the actual exam will look like. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jun 3, 2021 | Blog, Grammar (SAT & ACT), IELTS

There are three main types of conjunctions in English. Some words in different categories have identical meanings, but they have different grammatical functions. As a result, they are punctuated differently when used to begin a clause or sentence.

Although the conjunctions discussed below may also appear in the middle or at the end of a sentence in certain contexts, this post concerns their placement at the start of a sentence or clause only.

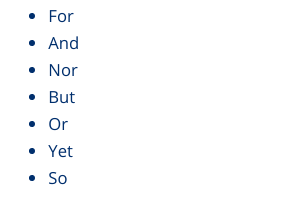

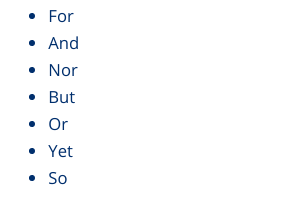

1) Coordinating Conjunctions (“FANBOYS”)

There are seven coordinating conjunctions, known collectively by the acronym FANBOYS:

These words are placed in the middle of a sentence to join two independent clauses and should follow a comma. Although the punctuation is often omitted in everyday writing, you should make an effort to use it because the comma serves to clearly separate the parts of the sentence and helps the reader follow your ideas more easily. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | May 31, 2021 | GMAT, Grammar (SAT & ACT), IELTS

Image by TypoArt BS, Shutterstock

I was looking back through my grammar posts the other day when I made a rather startling discovery: in all my years of writing this blog, I had somehow neglected to write a piece covering the two major causes of comma splices.

I suspect that because I’ve given this explanation in a total of five books now, I took it for granted that I had covered both issues in a single post, back in… oh, I don’t know… 2012 maybe? But apparently not.

Since this is among the most frequently tested concepts on the SAT and the ACT, an occasional target of questions on the GMAT, and a HUGELY common error in IELTS essays, I would count this omission among the greatest oversights in Critical Reader history.

So here goes. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | May 28, 2021 | ACT Reading, Phonics, Reading (SAT & ACT), Tutoring, Tutors

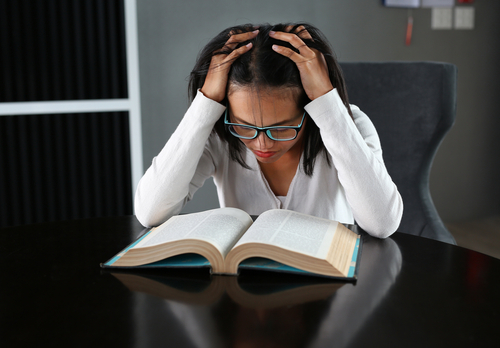

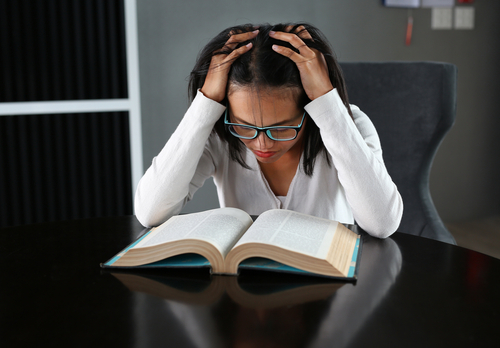

In a recent post, I talked about the challenges that (ACT) tutors often face when working with struggling readers; I also discussed how different types of problems can signal difficulties in different component skills that combine to produce reading. In this post, I’m going to cover how to identify a reading problem and provide some strategies for determining whether it stems from decoding, aural comprehension, or both.

To quickly review, the Simple View (Gough and Tunmer, 1986) states that General Reading Ability = Decoding x Aural Comprehension, with the weaker factor limiting overall skill.

Proficient teenage-adult readers decode at approximately 200 words per minute, or the speed of speech; however, many struggling readers never learned sound-letter combinations well enough to “map” them orthographically—that is, to store them in their brains for automatic retrieval. As a result, they read slowly and dysfluently, and may guess at, skip, misread, reverse, add, or omit letters/words.

On the other side, weak vocabulary (particularly words denoting abstract concepts); difficulty making sense out of complex syntax; and poor general knowledge can cause students who are solid decoders to have trouble understanding what they read.

Problems can be restricted to either of these areas; however, they often involve both factors and together produce a general reading problem. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | May 22, 2021 | ACT Reading, Blog, Phonics, Tutoring, Tutors

Image by GOLFX, Shutterstock

When Breaking the Code, the reading-instruction group I helped found in the summer of 2020, held its most recent workshop last week, I stuck an announcement in my newsletter almost as an afterthought. A test-prep tutor had participated in our previous workshop and seemed to have gotten a lot of out of it, and it occurred to me that others might be interested. Nevertheless, I was a bit taken aback at the number of inquiries I received from ACT tutors—more emails, incidentally, than I got from elementary-school teachers.

In retrospect, this should not have been at all surprising, but I guess that given all the current backlash over standardized testing, I neglected to realize how many students are still getting tutored for college-admissions exams, and how many tutors are encountering the exact same kinds of reading problems I repeatedly saw. The issues I discuss here do also apply to the SAT (and any other standardized test), but I’m focusing on the ACT here because it brings a set of specific issues into particularly sharp focus. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | May 21, 2021 | Phonics

One of my colleague Richard McManus’s favorite stories about reading instruction involves a young girl who was brought to his tutoring center to prepare for a private-school admissions exam. She was clearly very bright, and when she was asked to read aloud, she did so quite fluently. Richard assumed that she’d ace the test with little trouble. When he told this to her mother, however, the woman’s response was that her daughter sounded fine but in fact understood almost nothing of what she read.

Richard was baffled. Luckily, though his friend Jean Tucker—a speech-language pathologist, reading specialist, and creator of the Spell of Language program—happened to be visiting that day and overheard the child reading. She turned to Richard and promptly announced, “That little girl can’t hear vowel sounds.”

Richard tested the girl and discovered that Jean’s diagnosis was in fact correct: the girl could not distinguish between vowel sounds. As a result, she was unable to tell many words apart and thus could not comprehend what she read. Richard put the girl on an intensive diet of vowel sounds, and sure enough, her comprehension began to improve.

I’ve heard Richard tell this story a number of times, but it was only very recently that I connected it to the so-called “word caller” phenomenon, in which children decode with apparent ease but are unable to make sense out of what they are reading.

To back up for just a second, the Simple View (Gough and Tunmer, 1986) states that Reading Ability = Decoding Ability x Aural Comprehension. This is the generally accepted model of how people are (un)able to make sense out of written texts, and when you think about it, it’s quite logical.

Essentially, a person can be able to decode a text perfectly, but if the language involves vocabulary, syntax, and background knowledge above the level of their aural comprehension, they will not be able to understand it. This corresponds to basic observable reality: most skilled adults readers could decode an advanced engineering textbook with relative ease, but few would have the vocabulary or mathematical knowledge to understand what the text actually meant. For all intents and purposes, they would simply be reciting words.

When I was tutoring, I had several students who didn’t exactly fall into the “word caller” category, but whose decoding skills significantly outstripped their general language ability. In every case of this I can recall, the student had a diagnosed learning disability and had received significant intervention on the decoding side; their comprehension difficulties resulted from the fact that they had weak vocabularies, understanding of syntax, and general knowledge. The same issues would surface if someone read them a text.

Given that experience, when I started learning about early reading instruction and discovered the pejorative “word caller” epithet, I assumed that the issue stemmed primarily from the aural comprehension/general language development piece of the reading equation. But now when I think about Richard’s story, I realize that there can also be hidden decoding issues. It seems possible that some children who appear to be reading competently—or even well—don’t actually perceive vowels correctly and, as a result, don’t realize they’re saying words they know.

I realize this might sound a little wacky, but hear me out.

In my experience, very few learners experience difficulties that are truly unique to them; if one student is missing a particular skill, chances are lots of others lack it as well. It just might be that no one has ever noticed, or even thought to check. And this is particularly true for reading.

When it comes to learning to decode phonetically, it is almost impossible to overstate the importance of being able to perceive vowel sounds accurately—and in particular vowel sounds in the middle of words. Lots and lots of words are written with the same sets of consonants; changes in meaning are conveyed through vowels. Think bat, bait, bet, bit, bite, bought, but, boot, bout. A person who is not aware of the differences between those vowel sounds will struggle to connect them to specific letters/combinations of letters and thus to read words containing them.

The absolutely key thing to understand here is that this is not a speech or hearing problem but rather an issue of conscious aural discrimination. It is entirely possible for someone to be able to automatically pronounce vowel sounds correctly within words, and to be able to easily distinguish between spoken words that differ by only one vowel sound; and yet on a conscious level struggle to recognize, produce, and differentiate among those same vowel sounds in isolation.

This might seem very counterintuitive, but reality is not required to follow the rules of logic.

I confess that when Richard first showed me the Fluency Factory’s vowel chart (covering long vowels, short vowels, and diphthongs) and referred to “training” people on it, I was slightly baffled: it struck me as pretty much self-explanatory. The idea that someone could be able to say a word like book perfectly and automatically but then be unable to isolate the short “oo” vowel sound and say it on its own did not occur to me. It also did not occur to me that a person could find this exercise in any way awkward or unnatural or unpleasant. To me, sounds just were what they were, regardless of whether they happened to be part of a word or not.

When I observed Richard work with various students, however, I discovered just how much I was taking for granted. Differentiating between a short “oo” (as in book, look, cook) and an “uh” sound (as in but, cut, luck) turns out to be extremely challenging for some individuals, both children and adults. I did ultimately get some inkling of what this is like during a debate with Richard over a particular variant of short “o”. His usage was based on a pronunciation common in New England that never made its way into my speech, despite my having grown up in Boston, and it took me months to figure out that the sound was actually the pure “ah” sound used in father or avocado.

During the first Breaking the Code workshop, I briefly worked one-on-one with a kindergarten teacher who whizzed through the vowel chart, saying each sound flawlessly and without the slightest hesitation. When I complimented her, she shrugged and said that she was just looking at the example words on the side of the chart. For her, plucking a vowel sound from a word and saying on its own was completely effortless.

I realized then that I didn’t know how to impress upon her—or indeed anyone who can perceive and isolate vowels easily—just how difficult that skill can be, or what an utter, long-term train wreck it can cause if it isn’t developed. I tried to convey to her that some people simply cannot connect vowels in the context of words to vowels on their own, but I suspect that it’s a problem that needs to be seen in action to fully be grasped by someone to whom vowel perception comes naturally.

English has 18 vowel sounds (compared to just five in Spanish)! They comprise both pure phonemes and diphthongs and are spelled in many different ways—some very common and others less so. Keeping the spellings straight is hard enough; for someone who isn’t even sure of the sounds themselves, it’s basically impossible.

Furthermore, vowel perception in one’s native language develops naturally in a window from birth to 18 months; it can be explicitly taught after that, but if a child grows up in a non-English-speaking home, or has repeated ear infections that interfere with hearing, it becomes much harder. This is in part why ESL students struggle so much with English reading—and things only get harder if their English-resource teachers are not native speakers themselves. (In New York State at least, ESL teachers are required to have proficiency in a foreign language, which sharply limits the number of people who qualify for certification). A teacher whose own ability to perceive and demonstrate English vowel sounds is compromised simply cannot teach that skill effectively.

Again, speech and aural discrimination are two different things: it is possible for a student who is immersed in an English speaking environment at a young enough age to learn to speak without an accent, but that does not necessarily mean they will develop an awareness of the sounds they are producing and/or how they correspond to symbols written on a page. On the other hand, a student who begins learning English at an older age may retain an accent but still learn to aurally distinguish between similar English vowel sounds well enough to easily match the language they hear to written words.

But that said, I’m going to end this post with a slightly off-color anecdote recounted to me by fellow Breaking the Code member Valerie Mitchell, who teaches high-school French.

In the course of a recent texting exchange with another foreign-language teacher, a native Japanese speaker, Valerie happened to refer to a student named Inès.

The Japanese teacher wrote that she felt terribly sorry for the girl, with a name like that. Valerie was baffled. “But why?” she asked. “Inès is a lovely name.” Then it occurred to her to ask whether the sounds in the name meant something vulgar in Japanese. “No, no,” her colleague replied.

Valerie wasn’t convinced. Assuming that the woman was simply too embarrassed to say what the word meant, she gently prodded until her colleague’s reaction became clear: the Japanese teacher interpreted the letter I in the girl’s name as making an “ay” sound—something it never does—and the e as making an “uh” sound (sort of fair, since short vowels are sometimes reduce to a schwa in names).

As a result, she assumed the name was pronounced… anus.

True, she was not an ESL teacher, but she was a foreign-language teacher: someone whose job entailed paying close attention to sounds.

She still could not reliably identify match English vowels to some of their most common phonemes.

And she had been living in the United States for 20 years.

Just something to think about.

by Erica L. Meltzer | May 17, 2021 | Blog, IELTS

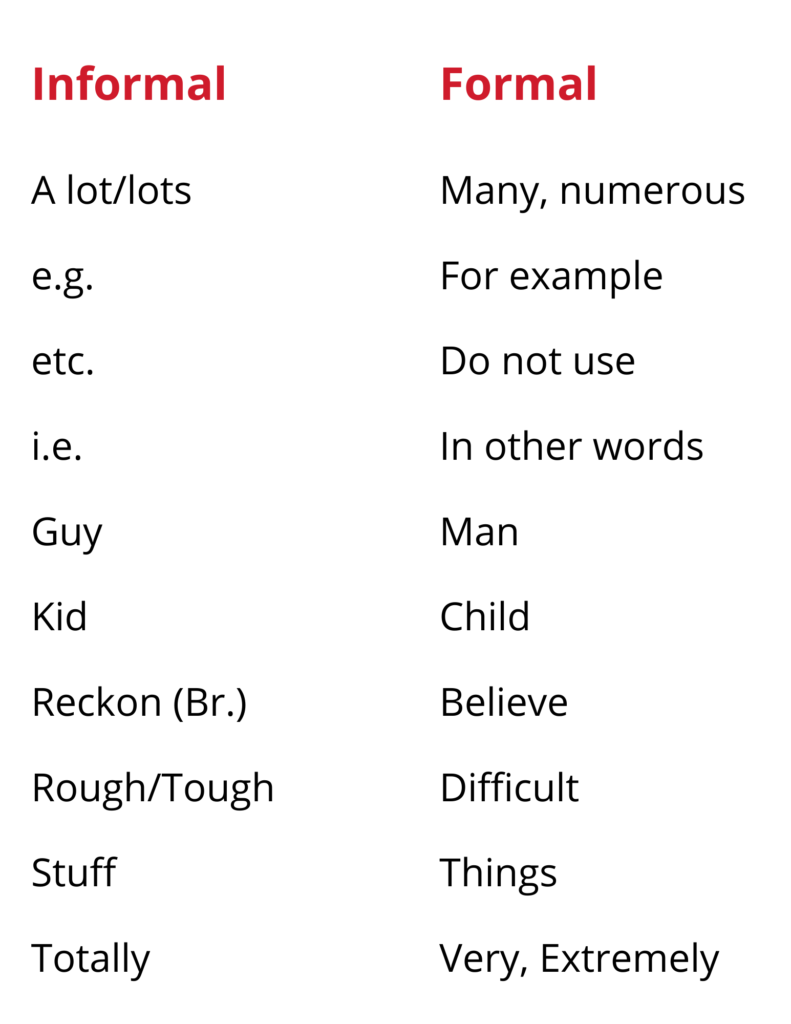

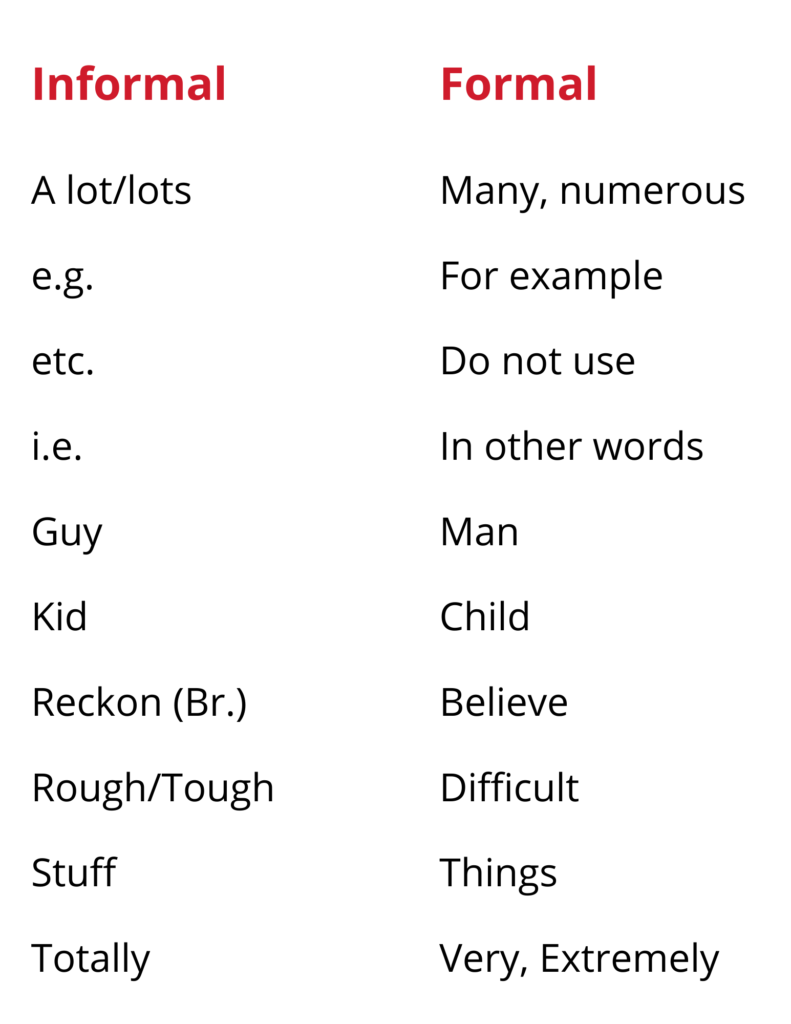

After reading a certain number of Band 6 #IELTS Task 2 essays, one (or rather I) can’t help but notice certain patterns. In particular, the persistent use of certain informal words, phrases, and abbreviations is quite striking.

I’m not the first person to point this out, or to post about it on the internet, but given sheer frequency with which they’re used, it’s clear that the message isn’t getting through.

So I decided to compile the greatest hits into one very short list.

Bottom line: if you stop using the informal terms, you’re taking a real step towards Band 7; if you keep on including them, expect your score to stay where it is. These are very high-frequency words and constructions, and they are relevant to pretty much any question you might be asked.

In fact, I would actually wager that it’s possible to accurately gauge, in only a few seconds, whether an essay has any chance of earning a 7 simply by scanning it for the terms in the left-hand column, plus standard punctuation, capitalization, and spacing.

Let’s look at a comparison: (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | May 13, 2021 | Blog, GMAT, Grammar (SAT & ACT), IELTS

Image by Charlotte May from Pexels

In theory, parallel structure is a relatively easy concept to master: it simply refers to the fact that items in a list, as well as constructions on either side of a conjunction such as and or but, should be kept in the same format (all nouns or all verbs).

In very simple sentences, e.g., I went to bed late but woke up early, this rule is generally quite simple to apply.

When sentences are long and contain a lot of information, however, things get a bit trickier. Keeping forms parallel requires the writer to keep track of and understand how words and phrases in different parts of a sentence relate to one another.

One very common issue involves the use of main verbs after modal verbs such as can, should, or might. As anyone who speaks English at a reasonably high level knows, main verbs are never conjugated in this construction, e.g., one would say it might work, not it might works. But when the two verbs are separated, there’s a common tendency forget about the first one and to stick an -s on the second.

This is an issue that appears in the writing of both native and non-native English speakers, but it’s particularly rampant in IELTS essays. It may also be tested in GMAT Sentence Corrections. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | May 9, 2021 | IELTS, Issues in Education, Tutors

Image from Andrea Piacquadio, www.pexels.com

I have a somewhat ambivalent relationship with social media. Given what I do and the nature of my audience, it’s pretty much a necessary evil, albeit one I dip in and out of depending on the demands of my other projects. For the past month or so, I’ve had a bit more free time than I’ve had in a while, and it occurred to me that perhaps I should make an attempt to revive my long-neglected Instagram account (a decision of which the algorithm unfortunately does not seem to approve). Having recently taken some steps into the world of English-language proficiency exams, I got curious and decided to explore the social-media ESL world. If nothing else, it was certainly an eye-opening experience.

I don’t have a clear sense of what proportion of my readership is made up of students living outside the United States, although my sense is that most of them attend either international schools or English-immersion programs and speak the language at a very high level. Based on some of the messages I’ve received, however, I’m aware that this is not the case for everyone.

For that reason, and because the internet has basically swallowed real life whole, I feel obligated to offer this warning: to anyone attempting to use social media to supplement their study for English proficiency exams (TOEFL or IELTS), please be extraordinary careful about whom you follow and take advice from. And if you are a tutor who works internationally, please make sure your students understand the difference between “Instagram English” and “school English.” To describe the linguistic misinformation out there as “mind-boggling” is an understatement. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | May 5, 2021 | AP

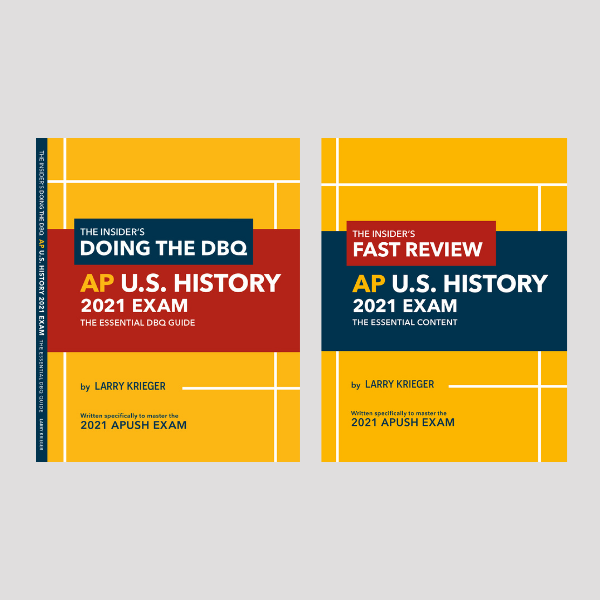

Larry Krieger, my friend, colleague, and APUSH master extraordinaire, has just released two new guides for the 2021 AP US History Exam.

The Insider’s Fast Review is a general overview of the exam content, boiled down to the absolute essentials:

The Insider’s Fast Review is an efficient review based upon the AP US History Course and Exam Description (CED) book and authentic APUSH questions and answers. It is an EFFECTIVE review of the key historic developments and patterns in all 9 required time periods. The Fast Review is designed to live up to its title. It provides you with a carefully organized presentation of the key developments, trends, and patterns you must know to achieve a high score on your APUSH 2021 exam. There are no fun facts and trivial topics. Everything in Fast Review is taken from the CED and APUSH questions and answers. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | May 3, 2021 | Blog

When I was putting together my IELTS grammar guide, I read dozens of practice essays, primarily by students who had scored in Band 6 on previous exams. It quickly became apparent that many test-takers were struggling with similar grammatical concepts, and one of the most common ones involved the use of articles with a specific group of “quantity” words.

On one hand, this is entirely understandable: a(n) and the are notoriously tricky for people whose native languages do not use articles the way English does, and it is often not fully clear to them why these words even need to be used at all. As a result, they may not realize how omitting them can change the meaning of certain statements and/or make their English seem unnatural.

In everyday life, this is unlikely to seriously impede communication; however, in terms of the IELTS—and particularly IELTS Writing—it can create real problems. Phrases involving words like majority and number are relevant to most IELTS Task essay questions (Task 2 as well as Task 1 Academic Training) and may need to be used multiple times within a given response. Furthermore, these terms are frequently used in introductions, and errors there can subtly influence a reader’s impression of an entire essay—a poor first impression can be hard to counteract.

So that said, here is what you need to know. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Apr 30, 2021 | Blog, ESL, IELTS

Over the past several months, I’ve read an enormous number of essays written by non-native English speakers, and in addition to the expected difficulties, I’ve noticed a handful of recurring issues that rarely get addressed — I suspect because most native English speakers don’t realize that the particular concepts in question can get confused in those particular ways.

One of the most common of these issues is the confusion between the simple present and the conditional, and more specifically between can and could.

Errors involving these forms are often fairly subtle; they’re not absolutely wrong in the same black-and-white way as errors involving, say, confusion between the present perfect and the simple past (e.g., I have graduated from university last year rather than I graduated from university last year), and I think that’s also why they tend to get missed. Using could correctly is often more about implication and context than adhering to a clear-cut rule, which is why even very advanced speakers may still struggle with it. (more…)