by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 14, 2019 | Blog, Phonics

Let me start here.

A while back, a colleague told me the following anecdote: a college classmate of her partner was visiting from San Francisco, and the three of them had dinner together. At some point, the conversation turned toward the classmate’s middle school-aged son, who had an interest in STEM, and the classmate said something along the lines of, “Isn’t it great that schools count computer science as a language now?”

“Wait,” my colleague replied. “Languages have four main components: reading, writing, listening, and speaking. CS has the reading and writing aspects but not the other two pieces. It’s not really a language in that sense.”

The classmate was taken aback. No one in the Bay Area had ever challenged him on that point—it was just taken as an article of faith that learning to code was an acceptable (and likely superior) alternative to learning, say, Spanish.

“Whoa,” he said, “I’ll have to think about that one.”

That’s part one.

Part two is that last November, Richard was kind enough to let me observe at the Fluency Factory, and as I observed him and his tutors work, that story kept coming back to me.

On my first day there, before I watched any actual teaching, I got into a conversation with a tutor who also worked as classroom teacher. As we talked about the kinds of reading issues she encountered, she mentioned that at the international school in South America where she had student-taught, the teacher she worked with required students to stop and think before speaking.

Initially, the kids were baffled, the tutor explained. They weren’t angry, just perplexed. They were accustomed to just sounding off automatically about whatever happened to pop into their heads; no one had ever insisted that they consider their thoughts carefully before talking. But they learned to do it. These kids were six and seven years old, and reading/writing really well in both Spanish and English.

Over the next few days, I watched the Fluency Factory tutors work valiantly with lots of struggling readers, generally between the ages of seven and thirteen. In a lot of ways, it was like a redux of all of the issues I saw as a tutor: misreading words, skipping words, skipping lines, guessing at unfamiliar words, vocabulary problems, background-knowledge problems…

I was consistently stunned by the similarities between these younger students and some of my own former students, who were high school juniors and seniors. I had known in some abstract sense that they were reading at perhaps a seventh-grade level, but watching those tutors have the exact same conversations I had had with my students, except with actual middle-schoolers (and again, a mostly affluent group), drove home the extent to which those students had been stunted academically. It also made me wonder about how bad things were with the kids who weren’t getting any intervention.

The other thing that repeatedly struck me was the students’ difficulty in reading aloud.

During the last couple of years that I tutored, after I had learned a certain amount about phonics and gotten a decent sense of what sorts of problems to look out for, I began asking new students scoring below a certain threshold—usually about 550 on the SAT, 24 or so on the ACT—to read out loud for me so that I could see whether they omitted/inserted/confused words, or guessed on unfamiliar terms. What I didn’t really focus on, however, was prosody—that is, whether they could read with conversational intonation.

As I listened to Fluency Factory students read, however, I couldn’t help but notice how jerky their speech was: they paid almost no attention to punctuation, nor did they seem to recognize where the pauses and emphases within a sentence would naturally occur.

They were opening their mouths and words were coming out, but the act had nothing to do with real speech.

It was as.

If they had.

No.

Concept of where thoughts.

Began and.

Ended.

Or, for that matter, that written language was even intended to convey thoughts.

For the youngest/weakest students, I chalked this up to the fact that the mere act of decoding required so much brainpower that they had nothing left over to make sense of what they were reading, never mind doing the two simultaneously.

But the older kids mostly read this way too, and it started to freak me out a little.

It was as if, at some level, they did not really grasp that reading is written speech.

Assuming that their out-loud reading was a general approximation of their silent reading, that certainly explained a lot of their comprehension problems.

Of course, I understood intellectually that they were not reading this way on purpose, that what I was hearing was a result of their cognitive overload, but on a visceral level I found it really disturbing to hear language fragmented in that particular manner.

On multiple occasions, I realized that the jerkiness had become so ingrained in my ear that I almost started talking that way.

At any rate, it was striking to watch how their reading immediately became more fluent when they took turns reading with a tutor. They seemed to absorb the more conversational tone by osmosis. Had decoding been the only issue, that wouldn’t have happened—it wasn’t as if they were merely repeating the same words after the tutor. Yet when they reread the passage aloud again, this time entirely on their own, those gains inevitably evaporated after a couple of sentences.

I’ve written a fair amount about the connection between reading and listening, but until now, I haven’t thought quite so much about the connection between reading and speaking. I think, however, that it’s yet another piece of the reading puzzle—and a seriously neglected one at that.

As I’ve pointed out before, the language that appears in written texts is often very different from spoken language. It tends to be more syntactically complex and to contain vocabulary that students don’t necessarily encounter in everyday life. As a result, it’s hardly a surprise that even very competent decoders can have difficulty recognizing how a given line of text would be spoken (as I saw constantly when I was tutoring the SAT). And as texts become increasingly complex as students advance through the middle grades, they become increasingly divorced from spoken language.

When I wrote about this issue before, I approached it only in terms of listening: my question was whether the denigration (and in some cases the outright prohibition) of direct, teacher-led instruction, and the obsessive emphasis on student-centered groupwork, had inadvertently inhibited students’ exposure to the kind of formal, structured adult speech that bridges the gap to more sophisticated written language.

I still think that’s a major problem, but now I have to wonder whether the type of speech students are expected to produce isn’t also playing a role. If students generally have little opportunity to listen to the type of speech that overlaps with written language, then they have even less experience creating it.

In other words, if students are primarily addressing their peers informally during class—and rarely or never required to, say, give structured presentations to their entire class or (horror of horrors) sit for oral exams—then they are also not getting practice in producing the type of speech that approximates writing. And if the spoken-written connection is never fully made and/or reinforced, students then have difficulty translating words on a page into something resembling conversational speech. Lack of exposure to sophisticated texts in turn further inhibits the development of their speech, and a vicious cycle ensues.

When this idea occurred to me, I couldn’t help but contrast the pedagogies that currently dominate in the American educational system with those of France and especially Italy, countries where there is a significant emphasis on oral presentations and exams at the secondary level. (I don’t have the same level of familiarity with any other country’s school system, so I can’t comment on what it’s like elsewhere.) Students are expected to address their classmates as well as adults using formal, structured language, and to present their ideas orally with a striking degree of eloquence using—this is key—linguistic features otherwise found only in academic writing (e.g., “We have seen x and will now turn to a consideration of y…”).

That’s not to say that French teenagers don’t still mumble incomprehensibly sometimes (and boy can they mumble!), but at a systemic level, it’s a different mindset and set of expectations. And regardless of the drawbacks these systems may have—and I am by no means suggesting they are above reproach—it’s hard to deny that they are set up, on a broad scale, to systematically inculcate a particular set of verbal capacities from multiple angles and in mutually reinforcing ways.

Indeed, when listening to French adults discuss, say, politics or philosophy (or wine), it’s hard not to notice how closely their speech contains what are often only written constructions. The relationship between the various aspects of reading and speaking and, ultimately, thinking is evident, in a way that makes the links impossible to ignore.

All this is to say that I no longer believe that reading is the “three-dimensional problem” that it has traditionally been described as. Rather, I think it’s even more complex. As is true for any language, becoming truly proficient in English requires mastery of four domains—speaking, listening, reading, and writing—that build on and feed into one another. And the tendency to treat reading as a skill that can be acquired in isolation, without significant work on the other three domains, is even more of a fool’s errand than I understood even just a short while ago.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 1, 2019 | Blog

Just wondering if anyone out there might know the answer to this.

From what I can glean from documentsl released by the College Board as well as various online discussions, the 2020 AP Lang/Comp test will be removing two kinds of multiple-choice questions: vocabulary in context, and something referred to as “identification.”

I cannot, however, seem to find out precisely what “identification” refers to.

My best guess is that it involves identification of rhetorical devices, but I can’t exactly remove a chapter from my AP Lang/Comp book unless I’m totally sure that the material is no longer tested!

Any AP English teachers out there (or people who know AP English teachers) who might be able to shed some light on this? I’d like to get the updated book out sooner rather than later.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Dec 1, 2019 | Blog

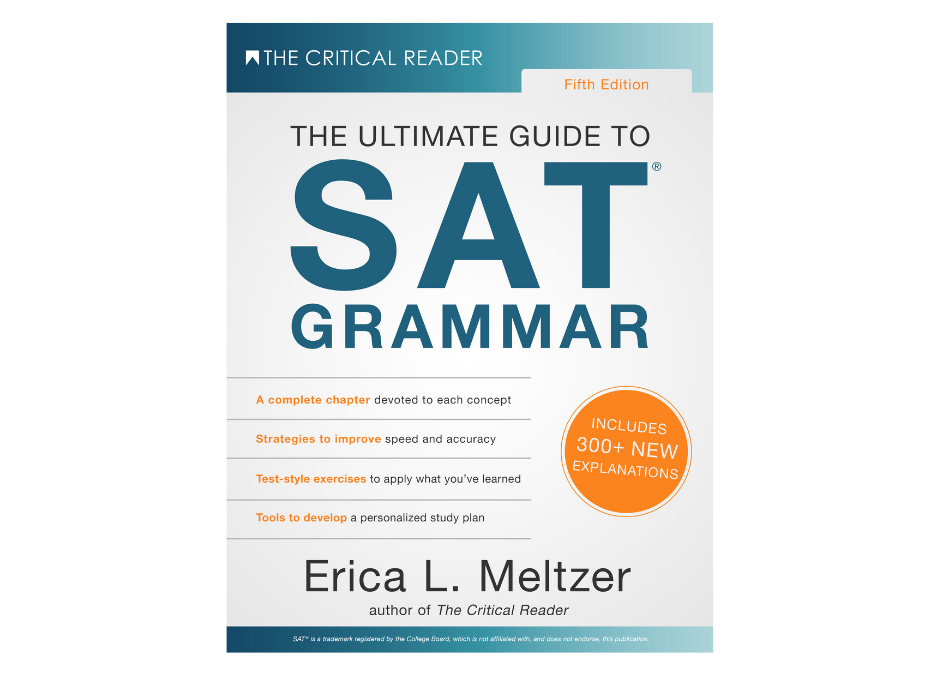

Complete explanations for the end-of-chapter exercises in The Ultimate Guide to SAT Grammar, Fifth Edition and The Complete Guide to ACT English, Third Edition, are now available online via the Books page for $4.95 each.

Click here to purchase explanations for the SAT book.

Click here to purchase explanations for the ACT book.

Please note that to access the explanations, you must return to the main item page and follow the link provided.

If you purchased one of the new editions (SAT grammar, 5th ed., ACT English, 4th ed.), this does NOT apply to you; explanations are included in the books themselves.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Nov 16, 2019 | Issues in Education, Phonics

Update, 11/20: I realized after I posted this piece that the problem I discuss in this post—namely, that most people don’t know what the three-cueing system is—ironically made the piece hard to follow. So if you’re unfamiliar with three-cueing and want the full background, see this post first.

If you want the short version, it’s this: basically, the three-cueing system is derived from the observation that skilled use a variety of “clues,” including spelling, syntax, background knowledge, to draw meaning from texts. Over time, that idea became profoundly distorted into the notion that children should be discouraged from using all the letters in a word to determine what it literally says, and should instead look at only the first/last letters, along with other contextual clues—usually pictures—to identify it. I’m simplifying here, but that’s the gist.

Original Post

A couple of weeks ago, a colleague of mine attended a mandatory development workshop for AP French teachers. During a discussion of the previous year’s main essay, she learned that the average score had been exceptionally low—a 1, in fact—because so many students had confused the main verb in the prompt, s’habiller (to get dressed), with habiter (to live in or inhabit).

Now, the s’ at the beginning of the former signals a reflexive verb (in French, one literally dresses oneself), whereas habiter can never be reflexive—from a logical perspective, one cannot live in oneself, and so this construction makes no sense. (Note to anyone new to this blog: I have a college degree in French and started out tutoring that language; the English thing happened more or less by accident.)

Nevertheless, an enormous number of French AP exam-takers failed to notice either these very important linguistic clues (despite the fact that students at this level should theoretically be able to recognize reflexive constructions easily) or their commonsense implications.

Beyond that, s’habiller and habiter are such incredibly common verbs that that a student sitting for the AP exam should obviously know the difference between them.

So why did so many students mix them up? (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Nov 2, 2019 | Blog, Issues in Education

Attention! This post has moved.

It can now be found here: https://www.breakingthecode.com/some-thoughts-on-the-2019-naep-reading-decline/

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 29, 2019 | Blog

I’ve received a couple of inquiries about the updated AP English Lang/Comp exam, so I’m putting this out there now: yes, I am aware that the test is being updated for 2020, and yes, I will be revising my guide for that exam. I’m aiming to get it out by around February 2020.

In the meantime, if you are self-studying for the exam and absolutely cannot live without a book now, you can use a combination of the current AP Lang/Comp book and either The Ultimate Guide to SAT Grammar, fourth or fifth edition OR The Complete Guide to ACT English.

The major change to the AP exam involves the introduction of SAT/ACT-style writing passages, and from the document released by the College Board, it appears that there will be a heavy focus on “is this sentence relevant?” questions. These are discussed in great detail in the grammar books. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 5, 2019 | Issues in Education, Phonics

Lest anyone should have read my last few posts and concluded that my depiction of the state of American reading instruction was exaggerated in some way, I direct you to the video below. If you’ve ever wondered why so many children struggle, this pretty much says it all; you basically get to watch reading problems being created in real time.

Notice that a couple of times, children attempt to use the letters sound out words, but the teacher reminds them to focus on the pictures instead. The clear message is that sounding out words is a strategy to be avoided.

The only times she acknowledges that letters have something to do with how the words are said is when she tells children to look at the first and last letters in conjunction with the pictures; the fact that the sounds in the middle of a word also play a role in how it is said is not mentioned, ever. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 4, 2019 | Issues in Education, Phonics, Reading Wars, The Science of Reading

A couple of days ago, I got curious about the state of phonics instruction in New York City schools and started googling away. I learned all sorts of fascinating things about the respective reigns of Joel Klein and Carmen Farina, and about the ongoing and pernicious influence of Lucy Calkins/Reading Workshop and Columbia Teachers College.

I also came across a well-intentioned an article in Chalkbeat about the struggles of some Brooklyn parents to get their dyslexic children into appropriate programs. The content of the article was disheartening but fairly predictable—what I found more interesting was the semantic confusion the writers displayed in a discussion of balanced literacy vs. phonics, and it got me thinking about how the standard reading-war rhetorical tropes get wielded.

Here is the article’s more-or-less typical spiel:

Balanced literacy advocates believe learning to read is a natural process, that enjoyment of reading is paramount, and that helping students understand the meaning of text is more important than teaching them the mechanics of reading.

But experts question whether it’s the best method for struggling readers.

The opposing approach, rooted in phonics-based instruction, emphasizes decoding how letters correspond to sound and how the sounds connect to form words. It can be dry and repetitive, but many experts say the method establishes a firm base that benefits a wide array of students.

Many students can learn to read through a balanced literacy approach, particularly when it’s complemented with additional reading and vocabulary work at home, the experts say. But for those who struggle — including those with dyslexia — balanced literacy can feel like being thrown into the deep end of a pool.

There are a few things to notice here:

First of all, the (conclusively debunked) belief that learning to read is “a natural process” is primarily associated with the Whole Language movement (although it is likely held by many proponents of Balanced Literacy as well); Balanced Literacy, in contrast, represents the attempt to bring an end to the reading wars by reconciling phonics and whole language.

Although in practice it often favors the latter at the expense of the former, in theory it pays lip service to both. But if education reporters for a publication dedicated to education cannot even keep their terminology straight, how can the public at large be expected to do so?

Second, note the the both-sides-ism (some people believe x, but others believe y), which clearly comes down on the side of “Balanced Literacy.” Even if the authors do mention grudgingly that “experts question” whether balanced literacy [sic] is “the best method for struggling readers,” nothing is mentioned about other readers—only that “many students can learn to read through a balanced literacy approach.”

Given that experts believe (and in fact have ample evidence to support) that phonics is the most effective means to teach decoding period, not just for children who struggle, this is a rather serious omission—especially since the writers link to Emily Hanford’s original piece on phonics for American Public Media, which makes that viewpoint abundantly clear. But it is as if their distaste for the premise is so ingrained that they are unwilling, or perhaps even unable, to acknowledge the actual argument being made. (Perhaps they are engaged in “making meaning”?)

Again: if education reporters cannot even lay out well-established views accurately, how can the public understand what is at stake?

Even when phonics is acknowledged to be helpful, it’s presented as the educational equivalent of spinach: good for you, perhaps, but also kind of icky. In contrast, whole language is something like a slice of pizza: gooey and tasty and oh-so-satisfying.

This is fundamentally a rhetorical problem.

Traditionally, the whole language/balanced literacy faction has played the rhetorical game much more effectively than the phonics people, appropriating the lexicon of romanticism (naturalness, wholesomeness, enjoyment) to their advantage and assigning the role of artificiality (rote learning, memorization, drill ’n kill) to their opponents, who are forced into the defensive position.

What’s interesting, though, is that the reality is exactly the opposite:

English contains about 250 graphemes—letters or letter-combinations that represent specific sounds—approximately 70 of which are commonly used. That might sound like a lot to memorize, but a child who masters these correspondences can sound out literally thousands of words and take a decent stab at many more that are not perfectly phonetic.

In contrast, a student who never masters sound-letter correspondences will essentially need to memorize, by rote, often in a dry and repetitive fashion, every new word as a random bunch of squiggles disconnected from the sounds they make, and over the course of their educations, they will need to do this thousands upon thousands of time.

Why have members of the phonics camp not seized on this fact? Why have they not shouted it from the rooftops (or from their Facebook accounts)? Perhaps because they take it as self-evident that if they just present the science, then people will listen , particularly if said people claim to be in favor of “critical thinking.”

They assume that if method x is shown to be more effective than method y, then of course schools will want to adopt it.

They also assume that because the logic behind teaching phonics seems so obvious—you can’t focus on meaning unless you can figure out what the words say—that there is no need to explain things further.

Those are reasonable assumptions, but they rest on the notions that 1) people are moved by logical arguments; and that 2) that the desire to actually solve problems outweighs institutional inertia and/or the instinct to cling to existing beliefs, no matter how misguided.

Effectiveness is beside the point here. (Besides, what is effectiveness anyway, and how can it truly be measured? Isn’t it more important that children learn to love reading than that they know how to break words into little pieces? Isn’t learning the point of education to inspire children to love learning so that they can become lifelong learners?)

I also suspect that proponents of phonics systematically underestimate the hold that romantic ideology has on the American classroom: anything presented as natural is assumed to be good; anything presented as artificial (sometimes including school itself) is presumed to be detrimental.

These assumptions are so deeply embedded in the discourse surrounding education that they must be acknowledged and dealt with directly if any headway is to be made.

So here is my modest proposal: if proponents of phonics want to make any progress with the general public, it is necessary to flip the existing narrative on its head and insist that PHONICS = CRITICAL THINKING (applying knowledge to novel situations) whereas WHOLE LANGUAGE/BALANCED LITERACY = ROTE MEMORIZATION (random squiggles disconnected from authentic language).

This narrative needs to get repeated over and over, ad nauseam. Don’t try to sound smart, don’t go on about science, or logic, or peer-reviewed journals, just “MEMORIZING WHOLE WORDS BY ROTE IS BORING AND UNNATURAL.”

It might be too late—but still, you just might stand a fighting chance.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Oct 2, 2019 | Issues in Education, Reading (SAT & ACT)

Of all the difficulties involved in tutoring SAT reading, the one that perplexed me the most was the inordinate difficulty certain students seemed to have in grasping the notion that the answers to the questions were *in the passage,* as opposed to in their head or somewhere on the other side of the room. As I wrote about in a fit of irritation many years ago, not long after I started this blog, it literally did not seem to occur to them to look back at the text, and I could not figure out how to get them to do otherwise.

That many tutoring programs treated the location of the answers as some kind of amazing secret baffled me even more. Where other than in the passage would the answer be? How was it possible that so many students seemed to struggle not just with understanding what various texts said, but with the idea that answers to reading questions were based on the specific words they contained? How could such absolutely fundamental notions of reading be so lacking that they could actually be packaged as tricks? (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 25, 2019 | Tutoring, Tutors

1) Teach real lessons; don’t just go over practice tests

Yes, the amount of time you can spend just teaching material is obviously subject to time constraints; and yes, there is a small subset of mostly high-achieving students who just need to take practice tests and go over what they missed. However, virtually all students in the low-middle score ranges are missing specific pieces of knowledge, and getting taught the material while working through actual questions that involve additional, potentially unfamiliar pieces of knowledge, is often overly taxing for their working memories—there are just too many pieces to juggle. Unless you are very pressed for time, use the student’s diagnostic to figure out what they actually need to learn, and spend some time just teaching it to them before gradually relating it to the test. Repeat for as many concepts as necessary, gradually moving to full-length sections and then tests as students become comfortably with the material.

(more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 15, 2019 | Blog

Announcement: the new editions of The Critical Reader (4th ed.) and The Ultimate Guide to SAT Grammar (5th ed.) are now available. Please note that orders placed through thecriticalreader.com will have longer-than-usual shipping times (expect approximately 5-7 days for delivery) for the next couple of weeks, until the new editions are stocked at our storage/shipping facility.

If you need the books urgently in the meantime, please order from Amazon: the reading book can be found here, and the grammar book here. (As of 9/20, the books do not appear to be consistently appearing at the top of Amazon searches even when the exact titles are entered, so we recommend that you use the links provided here to navigate to them.) (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Sep 13, 2019 | ACT English/SAT Writing

Dashes are a form of punctuation that is pretty much guaranteed to show up on both the ACT® English Test and the multiple-choice SAT® Writing Test. Because they tend to be used more frequently in British than in American English, they are typically the least familiar type of punctuation for many students. That said, they are relatively straightforward.

Dashes are tested in three ways. The first is extremely common, the second less common, and the third rare.

1) To set off a non-essential clause (2 Dashes = 2 Commas)

In this case, dashes are used exactly like commas to indicate non-essential information that can be removed without affecting the basic meaning of a sentence. If you have one dash, you need the other dash. It cannot be omitted or replaced by a comma or by any other punctuation mark. This is the most important rule regarding dashes that you need to know.

Incorrect: John Locke–whose writings strongly influenced The Declaration of Independence, was one of the most important thinkers of the eighteenth century. (more…)

by Lisa Dzialo | Aug 24, 2019 | Blog, Tutor Interviews

Bio

Tanya has been tutoring for 25 years. In college, she first pursued a major in math/science; however, she missed the humanities and made the switch to history. She also trained to teach and tutor the GRE and SAT CR and M for the Princeton Review.

After earning an education degree and a teaching certification, she pursued a 10 year career teaching reading, interpretation and writing in social studies classes, including AP US History. She continued to tutor math on the side and in Ridgewood, she worked as a teacher’s aide in Chemistry, Geometry and Alg 2 classes.

Tanya and her husband moved to Ridgewood (her hometown) with their two children and started The Ridgewood Tutor in 2012. She took official SATs at local high schools and earned an 800 in CR, a 790 in Math, and an 800 in Writing over the two times she took the test in 2015.

Strong scores don’t always necessarily translate into good teaching–that’s where those ten years of teaching have helped her develop the necessary planning skills. She has organized lessons for the SATs, ACTs and GREs from wonderful resource material that she hand-picked after much trial and error.

Educational/certification details: National Board Certified and state certified in social studies education by NJ and NY, she also holds a Masters Degree in Teaching from Teachers College, Columbia University.

Good to know: Tanya gives presentations featuring SAT and ACT tips several times during the year at the Ridgewood Library. Check out the home page of this site for upcoming presentations, or follow her twitter feed (which also features general college prep retweets).

(more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 18, 2019 | Blog, SAT Critical Reading (Old Test), SAT Reading

Announcement: I realize this is coming on the late side (long story involving proofreaders, How to Write for Class, and the Random House permissions office), but I am planning to release updated editions of my SAT reading and grammar books, as well as my ACT English book.

Now, before you get your knickers all in twist over which editions to buy, here’s what you need to know: (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Aug 11, 2019 | Blog

I’m happy to announce that my first foray into non-test-prep grammar is finally available on Amazon and The Critical Reader.

How to Write for Class: A Student’s Guide to Grammar, Punctuation, and Style is a comprehensive guide to the concepts students need to know to write effectively for school. Although there is some overlap with the SAT and ACT grammar books (and tutors/parents who remember the pre-2016 version of the SAT grammar book will see some familiar material), it is not aligned with any particular test and covers certain concepts in significantly more depth. Rather than treat grammar as a series of rules to be memorized, it emphasizes the logic behind the English language as well as the relationship between grammar and meaning, and provides answers to burning questions such as “why can’t you end a sentence with a preposition?” (spoiler alert: you can).

The approach taken in the book is also based on the observation that students often find it challenging to apply rules studied in isolation, or in terms of overly-simplified examples, to the more complex sentences they want to include in their own writing. As a result, How to Write for Class makes use of numerous examples from actual student papers, and walks students through the process of constructing the type of sophisticated but grammatically coherent statements that will raise their academic writing to the next level.

Click here to read a preview.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jul 16, 2019 | Blog, Issues in Education

I found myself stuck at home sick today, and unable to do pretty much anything other than lie flat on my back on the couch, I inevitably ended up trawling the internet and somehow found myself on Retrospective Miscue, a blog run by various members of the whole language community (including Yetta Goodman, wife/collaborator of Ken Goodman, the founder of whole language and one of the figures discussed in the article by Marilyn Jäger Adams I posted about recently.)

As I read through the posts, I couldn’t help but notice what seemed like a rather idiosyncratic connotation of the term “making meaning,” and it occurred to me that what scientists and, well, most educated adults understand by it is fundamentally different from what the whole-language crowd—or a certain segment thereof—means. The two groups are not simply having a theoretical debate; they’re living in two separate universes, one of which is based in reality and the other of which is not.

In the everyday world, I think most people would agree, making meaning involves decoding a text as it is actually written and integrating vocabulary, content, background knowledge, etc. in such a way that the reader comes away with an understanding of what the author is seeking to convey and is capable of generating a meaningful response. Before today, I more or less assumed that proponents of whole-language believed that teaching children to read via “authentic texts” and “literacy-building” activities would somehow magically result in their becoming able to accurately read decode the words on a page, as written, while simultaneously making use of all the other skills. (To be fair, some of them probably do believe this, but there’s another, more extreme contingent too.)

As I now realize, however, the goal of whole language is for the reader to construct a coherent, personally meaningful narrative, regardless of the exact words on the page. The symbols representing sounds are a mere suggestion (kind of like traffic lights in Naples); a student may interpret all of them as written, or he/she may not.

Rather than being viewed as a problem in need of correction, misreading words (a process referred to euphemistically as “miscueing”) is viewed as an exciting opportunity for the reader to construct his or her own meaning—and to practice examining how he or she constructs meaning, thus taking charge of the learning process—regardless of whether it truly corresponds to what is there. There is no need to impose “inauthentic” processes such as sounding unfamiliar words out in order to figure out what they actually are.

This, essentially, is the workaround for the inescapable problem that many children will not actually learn to decode effectively via whole language: rather than accept that the theory is faulty, its proponents seek to alter the terms of the debate by redefining reading itself.

Thus, it does not matter whether a student reads “pony” when the letters spell h-o-r-s-e because pony still makes sense and allows the reader to “construct a meaningful text.” Indeed a student who makes this error should be praised for “making meaning.” That it is not what the text actually says is unimportant.

One blog contributor described her work “remediating” a dyslexic twelve-year-old thus:

Over the last nine months, [she] and I have carved out space to help her revalue herself as a reader. Using rich texts [children’s picture books] such as Winnie Flies Again (1999) and The Napping House (1983), we began with miscue analysis and moved on to Retrospective Miscue Analysis (RMA). The idea, in the very beginning, was to prove to her that she was actually reading (she did not think she was). Her focus on fluency and decoding through various intervention programs obscured her vision of her own meaning making process as a reader.

We used RMA as a tool to demonstrate the remarkable high quality miscues she was making, and how high quality miscues are indicative of the incredible predictions her brain was making as she read. She came up with all kinds of excuses. I am just using the pictures. I memorized the book. Each time I quickly came to her defense, pointing out other amazing things she did, like her predictions that were either spot on, or far better than the author’s original story.

It would be hard not to feel sympathy for a girl caught in this type of situation. Having worked with several students who had taken a test a ridiculous number of times and scored poorly before coming to me, I’m well aware of the psychological roadblocks that can occur from ineffective teaching followed by repeated failure and frustration.

But while the approach outlined here might have improved the student’s confidence about reading, there’s nothing to suggest that it did anything to move her even remotely into the range of her seventh-grade peers, or that it gave her the skills to navigate anything beyond very basic texts.

More worryingly, helping students who are performing at a very low level to feel more confident via immense amounts of support can easily backfire, allowing them to assume that they understand much more than is in fact the case, and leading them to much bigger misunderstandings.

The irony is that advocates of this approach often frame it in terms of wanting students to become creative, critical thinkers, as opposed to automatons slavishly adherent to a single “right” way of thinking. The ultimate, long-term goal, of course, is to encourage students to become independent thinkers, but there is a rather clear line between a judicious sense of skepticism based on accumulated knowledge and life experience, and a childish, knee-jerk, “Well, why should I believe anything you say?” based on the shallow belief that everyone’s opinion is equally valid, and that no one knows more than anyone else.

Yet the belief that any form of direct instruction—or even the simple acknowledgment that specific combinations of letter make specific words and not others—risks turning children into nothing more than docile sheep, contributes to precisely the latter attitude.

And lest you think I am making a caricature out of this position, here is Yetta Goodman on the danger of insisting that young readers hew too closely to the letters on the page:

Teachers can send unintended messages that keep the reader focused on sub-skills and distract them from meaning making. When the teacher says, “Look at the word closely for the little words in the big words,” or “Check the beginning and ends of the words to make sure the sounds are right,” the reader interprets this as “Here’s the right way to say the word; say it my way and you’ll be fine.” Rather than taking a risk to make personal meaning, readers become very good at manipulating the teacher’s help. If they pause long enough and keep their eyes cast down, or look up with a pleading expression, they can get the teacher to say the word. If the reason for telling a word to a student is to get through a lesson, then that also becomes the pupil’s goal.

Undoubtedly, some students do become highly adept at getting information out of teachers this way, especially if they’ve learned that they will eventually be fed the answer. (A lot of my students were shocked at first when they asked me whether a particular option was correct, and I just shrugged and said, “I don’t know, you tell me.”)

And if teachers have had it drilled into them that their goal is to keep students constantly happy and excited about learning, then they are entirely likely to intercede with the answer when a child’s discomfort becomes too obvious. (Incidentally, international comparisons have shown that American teachers are more likely than teachers in countries with stronger school systems to turn difficult conceptual problems into simpler procedural ones, depriving students of the very important—but potentially unpleasant—experience of struggling through them.)

Several distinct issues are conflated here, though: having children look for little words in big words, or telling them check the beginning of a word to make sure it begins with the same consonant they are saying, and directly telling a child what a word is, are in two entirely different camps. The former two are tools (albeit three-cueing tools of questionable effectiveness) that students can use to figure things out own their own; the latter is intended to remove any discomfort by simply providing the answer. (Encouraging students to sound out words is of course strictly forbidden—this is referred to only as “an unintentionally taught strategy.”) To lump these approaches together and then criticize them for impeding students’ ability to “make personal meaning” (i.e., make things up) is really astounding.

Moreover, the language here is unintentionally revealing about the whole-language worldview: if reading what a word actually says is framed as “my [the teacher’s] way,” the terms of the discussion are moved from the general/social (words are always written with the same letters so that everyone can recognize them) to the personal (the word is x because this particular teacher says so).

It is as if the only conception of reading imaginable were a selfish one. Children are portrayed as wanting to manipulate teachers into providing answers (understandable if they have received little to no direct instruction), and there is no acknowledgment of the fact that teachers insist that h-o-r-s-e spells horse not because they have personally decided that is the case, but rather because the entire English-speaking world has a well-established agreement about it. Sometimes there is a right answer, and to lead children to believe otherwise is grossly unfair in the long term.

Of course, young children lack the perspective to grasp this context, and so it is the educational community’s job to understand it for them. In Goodman’s view, however, a teacher does not serve as a conduit between a child and the larger world; rather, one personal interpretation is pitted against another.

But learning to read means becoming part of a literate community—and community membership is by definition based on common understandings. A child who is explicitly taught to reject those understandings will thus be unable to participate in it effectively (and, worse, may actively attack it for refusing to accede to his or her individual and erroneous insistences). Teachers who fail to grasp that their role is to help children become members of a group that extends far beyond themselves, and far beyond the teacher even, are doing students a very grave disservice.

In addition to that, the message that gets sent is that other people’s words—indeed, external reality—do not really matter, only what makes sense to the individual reader. If ever there were a recipe for producing a society full of individuals hellbent on disregarding information inconsistent with their pre-existing narratives, I think it’s pretty fair to say that this would be it.

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jul 14, 2019 | Blog, GMAT

Thank you to Soph Lundeberg at Soph-wise Tutoring in San Diego for calling this to my attention.

Soph wrote:

The following Magoosh blog claims the GMAT will not test “so as to” versus “so that,” and furthermore, the two are idiomatically acceptable.

The solution for #150 is on page 302. Erica’s solution says “All of other options are idiomatically unacceptable” but does not have any further explanation for why A, “so as to escape,” is wrong, whereas the longer construction, “so that she could escape” is correct. If two constructions are acceptable, “shorter = better”, right?

I checked the Magoosh blog post, which claimed that the GMAT would never ask test-takers to choose between “so that” and “so as to,” and something really did not sit quite right about it.” There was just no way I would have bothered to put “so that” and “so as to” head to head in a question unless I’d actually seen the GMAC do so first. (more…)

by Erica L. Meltzer | Jul 6, 2019 | Blog, Vocabulary

In the course of my recent research on the phonics debate, I came across an idea that in retrospect should have seemed obvious but that nevertheless seemed entirely surprising when I encountered it—namely, that a reliance on context clues is a strategy employed primarily by poor readers.

Consequently, when schools teach young children to use context clues as a decoding aid, they are actually encouraging them to behave like weak readers. Strong readers, in contrast, rely primarily on the letters themselves to figure out what words are written.

According to Louise Spear-Swerling, professor of Special Education at Southern Connecticut State University:

Skilled readers do not need to rely on pictures or sentence context in word identification, because they can read most words automatically, and they have the phonics skills to decode occasional unknown words rapidly. Rather, it is the unskilled readers who tend to be dependent on context to compensate for poor word identification. Furthermore, many struggling readers are disposed to guess at words rather than to look carefully at them, a tendency that may be reinforced by frequent encouragement to use context. Almost every teacher of struggling readers has seen the common pattern in which a child who is trying to read a word (say, the word brown) gives the word only a cursory glance and then offers a series of wild guesses based on the first letter: “Black? Book? Box?” (The guesses are often accompanied by more attention to the expression on the face of the teacher than to the print, as the child waits for this expression to change to indicate a correct guess.) (more…)